Over the last two decades, Edmund McMillen has made a name for himself in the game industry as one of the preeminent hitmakers in the independent development scene. Whether you’re talking about his early days churning out cult-classic games with Adobe Flash or his mainstream success with titles like Super Meat Boy and The Binding of Isaac, McMillen is one of the greatest success stories to come out of the millennium’s early indie boom. And yet, through all this success, McMillen has felt like an outcast.

We sat down with McMillen for an extended conversation to learn about the unique path the artist and designer took to become one of the most successful independent game developers of this era.

New Paths to Newgrounds

McMillen has long felt like he doesn’t belong. Hailing from Watsonville in Santa Cruz County, California, McMillen mostly grew up with his grandmother. His mom’s side of the family, including his grandmother, consisted of devout Catholics, while members of his dad’s side were what he called “A.A. Christians,” or born-again Christians recovering from addiction.

“I didn’t fit in really anywhere in my family,” says McMillen. “I just felt like a giant weirdo. The closest thing to me was my grandma. Nobody else really had any interest in art. My dad sang in a Journey cover band, but other than singers, there weren’t artists, illustrators, or creative types.”

To this day, McMillen is a massive fan of music, even calling it a bigger inspiration on him than other media. As he sports a Nine Inch Nails t-shirt, he rattles off his favorite bands, including The Smashing Pumpkins and The Breeders. McMillen says he found himself drawn to the level of independence musicians have when crafting their art and the way they can express themselves.

“That was the thing I always strived for as an artist: the idea that this small group of people could sit down and do and write whatever the f— they wanted, and then thousands of people would hear it and could enjoy it was just so cool to me,” he says. “That’s what I wanted primarily – the same thing for animation and anything that I was doing. I wanted my voice to be heard so desperately.”

McMillen floated through high school, feeling like he didn’t fit in there either. However, he loved drawing, so he started self-publishing comics. Following a rejection letter from an indie comic publisher, McMillen had a fire lit under him. “It was one of those failures that motivated me heavily,” he says. “Not only did I want to show them up, and show them what they missed, but also, I got real and was like, ‘Okay, if I want to continue doing this, I can’t just keep printing 50 comics at Kinko’s and selling them at Streetlight [Records in Santa Cruz].’”

This led him to begin taking classes at a community college to learn web design to create a website to showcase his comics to a broader audience. He transitioned to putting his work online, with Flash becoming his weapon of choice thanks to its popularity as a web tool at the time. Shortly after, McMillen discovered Newgrounds.com, which hosts user-created games, movies, and other content.

Dead Baby Dressup!

Dead Baby Dressup!His first taste of success as a game developer came with Dead Baby Dressup!, a series of interactive Flash games based on his comics. He bought a domain for his comic series, This is a Cry for Help, and began experimenting more with Flash and implementing interactive elements.

“I didn’t choose games; games chose me,” he says, laughing. “I wanted to make comics. The thing is, even on Newgrounds, my animations didn’t do that well; it was my games that did well.”

His work eventually caught the eye of Tom Fulp, founder of Newgrounds. “He promoted my work pretty heavily and showed me the way,” McMillen says. “I didn’t know I was making games, even when I was making Flash games back then. There wasn’t even a category for games yet. They were just considered Flash animations that have interactivity to them.”

McMillen and Fulp began working on a game McMillen designed, but Fulp had to stop working on it to focus on another game called Alien Hominid. Fulp had grander ambitions for Alien Hominid than publishing it on Newgrounds; he wanted to bring the game to consoles. McMillen couldn’t wrap his head around the idea of getting a game made in Flash to consoles, but Fulp had his mind set on it.

Fulp’s Alien Hominid HD for Xbox Live Arcade

Fulp’s Alien Hominid HD for Xbox Live ArcadeTo accomplish this, Fulp co-founded a studio called The Behemoth. McMillen’s collaboration with Fulp on that project fell through, but the success Fulp and The Behemoth experienced with Alien Hominid and Castle Crashers served as early showcases for what indie games could accomplish in the home console market.

McMillen still didn’t feel like he entirely fit in despite the attention and audience he found online through sites like Newgrounds. Instead, he felt somewhat of a rivalry with other creators on the site, which drove him to become better at his craft. Over his first decade in development, McMillen created nearly 40 games, some of which were collaborations with other programmers within that same community. But, like Fulp, McMillen was thinking beyond Newgrounds.

Carnivorous Console Conception

In the late 2000s, McMillen compiled what he refers to as a portfolio of sorts, containing all of his games, comics, and animations on one disc, which he, alongside his wife Danielle, sold out of their house. He saw what his fellow indie devs achieved through the newly established Xbox Live Arcade and wanted in on the gold rush. “Suddenly, my peers were becoming millionaires, and they were having these options for their futures, and I would really like the same,” he says.

One day, McMillen received an email from then-Epic Games designer Cliff Bleszinski telling him he bought his disc and liked what he saw. McMillen viewed this as his chance to get his foot in the door with the console market, and upon request, Bleszinski gave him contacts at Microsoft and Nintendo.

Gish

GishAfter sending emails to both, McMillen received an enthusiastic response from the Xbox Live Arcade team. McMillen initially pitched them on a remake of one of his most successful games: Gish. McMillen reached out to original Gish co-designer Alex Austin and Tommy Refenes, another programmer he met through Newgrounds, to work on the XBLA version.

However, as the Gish project began, things quickly headed in the wrong direction, and development halted, with McMillen departing the team. Despite this, McMillen knew this was his big chance, and he couldn’t just walk away from the opportunity, so he began looking at what his most successful recent Flash games were. The one that stuck out to him was a 2D platforming game called Meat Boy.

McMillen showing then-Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé a demo of Super Meat Boy

McMillen showing then-Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé a demo of Super Meat Boy“It had eclipsed all of my other games as far as views go, and it was the most mainstream-appealing game on the internet that I had done,” McMillen says. “It was the most simplistic as well; it was a platformer, so it didn’t even involve physics. It was just straightforward.”

McMillen pitched a Meat Boy port to the Xbox Live Arcade team and asked Refenes to program it. When all parties agreed to it and development started, Super Meat Boy was born. As release neared in 2010, Microsoft informed McMillen and Refenes, or Team Meat as they’d become known, that the sales projections for Super Meat Boy were low thanks to it being a 2D game. Despite this notion, Super Meat Boy was bolstered by strong reviews and Team Meat’s grassroots promotional efforts.

McMillen during the filming of 2012’s Indie Game: The Movie, which chronicled the development of Super Meat Boy

McMillen during the filming of 2012’s Indie Game: The Movie, which chronicled the development of Super Meat BoyMcMillen’s highest hope for the game before release was that it would sell enough that he and his wife could afford a mobile home in Santa Cruz. According to McMillen, the sales helped him hit that mark in the first couple of weeks, and when the dust had settled (and the housing market crashed around that same time), he was able to afford something far nicer than his original target.

Super Meat Boy sold hundreds of thousands of copies and gave McMillen mainstream recognition and a certified hit on consoles.

The Unbinding of Edmund

To this day, Super Meat Boy is a beloved title synonymous with McMillen, but rather than create a sequel, he wanted to forge new paths. “[The success] screwed with me a little bit because there was an expectation,” he says. “Everybody wants a sequel, and the first thing I said was I would never make one. I would never make a sequel to Super Meat Boy because how could I do it better than that?”

Unfortunately, that’s where he and Refenes differed. According to McMillen, Refenes wanted to make it into a franchise (and he did, eventually releasing Super Meat Boy Forever under the Team Meat moniker in 2020), but McMillen didn’t find the idea of a sequel creatively gripping, and it led to a rift between the two. “I think we were just moving in very different directions, and we wanted very different things,” McMillen says. “The option was there to do The Binding of Isaac as a Team Meat game, but Tommy did not want to. I think he wanted to work on more Meat Boy stuff, which he did. I found out quickly that we were extremely different people.”

Shortly thereafter, McMillen left Team Meat to resume developing games under his name. His instinctual reaction to these expectations of a sequel or franchise was to defy them and begin work on something completely different less than nine months after Super Meat Boy. The result was The Binding of Isaac, a top-down roguelike game that takes inspiration from The Legend of Zelda series.

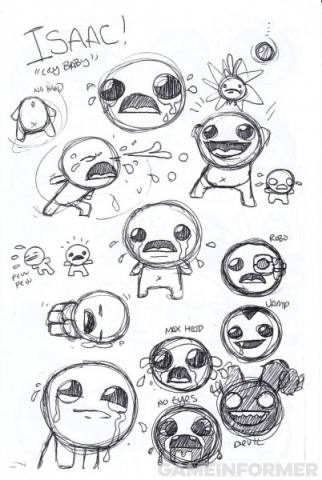

The Binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac“I wanted to get back to the headspace of not caring about money, like in the Flash days, not caring about ESRB rating, not caring about who I may or may not be upsetting, not caring about impressing some faceless suit, or whatever else; just do whatever I want to do,” he says. “Even though I didn’t make huge compromises with Super Meat Boy, it was me playing it safe because I knew what was on the line, and I knew what I was risking.”

To work on The Binding of Isaac, McMillen reignited a previous collaboration with Florian Himsl, a Newgrounds programmer he worked with on several Flash titles in the 2000s. The Binding of Isaac draws heavily from McMillen’s experiences as a child, delving into topics of religious fanaticism, feeling like an outcast, and the worlds we escape to in our minds during challenging times.

For this project, McMillen returned to his favorite source of inspiration: music.

“There’s something about how music is written that speaks to me a little bit more than traditional game design,” he says. “Kind of in the way that the story and the theme of The Binding of Isaac is written more like the lyrics of a song with visuals than it is a traditional story in a book or movie. I pull more from that: more from abstract poetry and words to set the tone that gives you these little empty spaces that you can fill in, instead of this drawn-out explanation of everything in a story structure.”

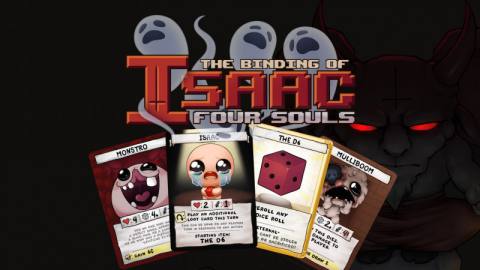

The Binding of Isaac launched in 2011 and has sold millions of copies and continued to grow through multiple releases across its decade of existence. McMillen initially decided to expand on the game because his wife got really into playing it, and he wanted to create more content for her. However, the personal nature of the game drove him to continue creating in the universe, even releasing a prequel deck-building game called The Legend of Bum-bo and a Kickstarter-funded tabletop game called The Binding of Isaac: Four Souls amidst the various main-game expansions.

“[The Binding of Isaac is] the only game I think I’ve worked on that I’ve been so brutally honest, and I want so desperately to paint this picture of what it’s like to grow up as a poor, single-parent household’s kid, who’s a creative weirdo and doesn’t fit in anywhere,” he says. “Writing from that perspective and being able to tell that story in an abstract sense felt very important.”

Despite the continued focus on The Binding of Isaac, McMillen continued working on new games, once again linking up with an old Newgrounds collaborator. McMillen reconnected with Tyler Glaiel, with whom he had worked on various Newgrounds titles years prior. Together, they released The Basement Collection, a 2012 compilation of McMillen’s old Flash titles for PC, Mac, and Linux.

Five years after The Basement Collection, McMillen and Glaiel joined up to create The End Is Nigh. Thanks to its gameplay style and punishing difficulty, many drew comparisons to Super Meat Boy. While the parallels are easy to make, McMillen thinks The End is Nigh stands above the rest of his catalog.

The End is Nigh

The End is Nigh“It’s the most beautifully elegant game that I’ve ever made,” he says. “In a lot of ways, The End is Nigh was my version of Super Meat Boy that was more true to who I am and more brutally honest about where I was in the world at that time.”

Just as he did with The Binding of Isaac, McMillen wrote autobiographically, this time dealing with his struggles with mental health. “I wanted it to feel like you’re riddled with anxiety at all times, and it felt like this looming, horrible darkness over you and that you’re always waiting for the next shoe to drop, and it never does,” he says. “I wanted you to feel panic. I wanted you to feel anxiety. I was not feeling mentally well at the time, and I wanted to simulate that in a game form.”

Oddly enough, McMillen thought that The Binding of Isaac, with its abstract ideas and more difficult-to-describe premises, would be his cult hit, but it turned out The End is Nigh was, as he describes it, his “arthouse midnight movie.”

The platformer launched in 2017, and the designer’s work again received positive reviews, but it did not receive the same mainstream attention as games like The Binding of Isaac. However, McMillen returned one last time to his biggest hit to release Repentance, the final planned expansion in Isaac’s journey. The 2021 expansion serves as a fitting bookend to the previous decade of McMillen’s career and the last foray into that world – at least for now.

The Binding of Isaac: Afterbirth

The Binding of Isaac: Afterbirth“I’m done … until I decide to make a sequel in like 10 years,” he says with a smirk. “I need to become a better designer. I need to grow more because I’ve had like five years of stagnation and kind of playing it safe with my projects that I’ve been doing.”

McMillen has found a new lease on design through Mew-Genics, a revitalized project from his Team Meat days that he describes as a combination of Pokémon, Animal Crossing, Final Fantasy Tactics, and Dungeons & Dragons. After shelving it for nearly 10 years, he’s again making good progress on it, once again joining forces with Glaiel. He estimates Mew-Genics is still about two years from release, but he’s happy with where he is on the project and how he’s once again growing as a designer.

No End In Sight

As McMillen charts his path forward, he hopes to continue sharing the characters and worlds in his head with the same level of freedom and uncompromised vision as those musicians he admired growing up. Following the release of Mew-Genics, McMillen wants to take a few years off from big games and create smaller titles every few months to scratch his creative itches.

During his two decades making video games, McMillen has focused on creating the kinds of experiences he’s wanted to make – with minimal compromise – rather than what would appeal to a mainstream audience. The approach has worked for him, as he has forged his own path to create unforgettable experiences, with any fame or fortune largely being a side effect of the work he produced.

McMillen may still feel like somewhat of an outcast, but perhaps that’s precisely why his work resonates with so many people. When you combine that notion with brutally honest writing, striking visuals, rock-solid gameplay, and inspiration drawn from some of the greatest games of all time, it’s a recipe for why critics and fans alike continue to eagerly anticipate his work and welcome his creations into their lives time and time again.