This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 392 in January 2024, as part of our Reinstall series. Every month we load up a beloved classic—and find out whether it holds up to our modern gaming sensibilities.

Despite Homeworld 3's recent delay, the launch still isn't far off. Looking back, the original game remains an enigma. It's not directly available on Steam, or even GOG. To play it as it was you need the original discs and a PC that can accept them, and this means it hasn't had any official updates to allow it to run on modern machines. Unless you're one of those weirdos from the Hardware section of this magazine who keeps a 1999-spec PC in a special room with The Matrix and Red Hot Chili Peppers posters on the walls, there's a good chance you're not going to be able to play it.

Unless, of course, you install the Homeworld remastered edition, which came out in 2015 and so practically counts as retro itself. That's what I'm reinstalling here, as my copy of the original disappeared years ago along with my Matrix posters. You can play the 'classic' version of the game through the remastered version's launcher, but I wouldn't recommend it: not only does it not seem to support 16:9 resolutions, but turning the res up above 1999 levels brings all sorts of scaling issues on modern screens, rendering text pretty much unreadable.

The Steam version of the game also now comes with a splash screen advertising Homeworld 3 and asking you to wishlist it, which completely filled my main 4K monitor and overflowed to my second screen, pushing any OK or close button off-screen somewhere I couldn't see. It necessitated a Win + Tab and closing it in the task switcher before I could even get to the launcher and start the game. Hopefully this will be patched out once the new game's released.

Spaced

The amazing thing, in 2023, is how fresh it all feels once you actually get into space. There was nothing like it in 1999, and relatively little to compare it to in 2015. There were plenty of RTS games in the '90s—Age of Empires 2 came out the same year—but they were earthbound things in which land, or occasionally water, units ran at one another in formations if you were lucky, or individually if you were being forced to micromanage. The feeling of being in a 3D space in which you could spin the camera and examine your space fleet from any angle, was revolutionary. A modern graphics card helps enormously here, the Voodoo 3s and early Nvidia cards at the time tried very hard, and it was the ideal game for showing off what your PC could do, but being able to play the game in 4K today trumps all of that.

The problem with a true 3D space game is that it's complicated. Approaching a star base in Elite Dangerous from the wrong angle means not getting through the landing slot, so commanding a small force of fighters and frigates in Homeworld would be impossible, ships impossible to see or select because they were hidden behind a much larger craft, or just outside your viewport. Luckily you can set formations, select ships with a drag of the mouse as if they were icons on the desktop, or use the keyboard to select all combat ships and sic them on the enemy. It works, but with WASD bound to their own shortcuts, leaving the arrow keys and mouse to control the camera, the early missions are an exercise in getting to grips with the controls as much as testing your hyperspace drive. Rarely has there been a game in which the tutorials are so essential.

The story at first seems utopian. A set of warring clans on a desert planet dig up a crashed spaceship and with it a star map. This discovery unites the population and they spend 60 years building a mothership to take them to a place on the map marked as 'home'. Ten years before launch a resource ship sets off, just so it can be in the right place for a test of the hyperdrive. Karan S'jet sacrifices herself to become Fleet Command, merged in with the mothership's computers like a primitive Borg queen. It's all meticulously planned, and goes off without a hitch. Except the galaxy isn't amenable to the apparently benign exploratory ideas of the Kushan. They're attacked as soon as they leave their solar system, returning to their planet to find it razed, the remains of the population in orbiting cryopods that need to be defended. It gets worse, with the discovery that the Kushan are the bad guys, a former imperial power exiled to the desert world under penalty of death should they ever leave it. It wouldn't be an RTS without a few enemies, and Homeworld pits an entire galaxy against you.

A panic unique to the RTS sets in as you race to keep up with all the things tugging at your attention.

If you've ever seen the heartbeat telemetry chart from Apollo 11's landing, which shows Buzz Aldrin—who wasn't at the controls—barely breaking a sweat as Neil Armstrong manually pilots the craft down and lands on the goddamn Moon, you'll understand the vibe of the comms chatter. From the calm, smooth pronouncements of Fleet Command to the cool professional way your interceptor pilots announce they're going after enemy craft, or resource collectors tip you off that they've run out of space rubble to mine, the sense in Homeworld is that you're in charge of a well-oiled machine. The person playing the game, however, is rarely following the example of Dr Aldrin. A panic unique to the RTS sets in as you race to keep up with all the things tugging at your attention, from build queues to repairs to that phalanx of red dots approaching the mothership.

Happily, you get a decent range of toys with which to splat those red dots. You start with a few scout ships, which seem to be armed with the equivalent of muskets, taking so long between shots you can imagine the crew pouring powder down the barrel. They're effective to begin with, though, and open the door to heavy corvettes, guided missile frigates, the hilarious salvage frigates that can literally steal enemy ships and convert them to your side, and my favourite, the beam frigates, which are as close to glittering in the dark off the shoulder of Orion as you're going to get. There's a classic balancing act at play, with those beautiful beam frigates deadly against other large ships, but easily picked apart by a cloud of fighters, which you can guard against with drones or assault frigates, and so on.

Golden age

Playing Homeworld today drives one thing home hard: how good we have it. If this game were made today, it would have a control scheme adapted for a controller, visual lists of ships from which you could pick the ones you wanted instead of relying on keyboard shortcuts to choose idle combat units or resource collectors. The icons to switch between tactics and formations would be larger. You wouldn't have to hold Shift and the right mouse button—which is also bound to camera control—to choose options from a menu. Maybe you could zoom out to the tactical map using the mouse wheel rather than having to hit the spacebar. My favoured screenshot button wouldn't have a command attached to it that centres the camera on the mothership.

And it would also be full of people. One of the reasons Homeworld has aged so well, and weathered the remastering process to come out the other side looking like a new game, is that it keeps its human figures to cutscenes. Human faces from this period are deep in the uncanny valley at best, and absolute nightmares at worst. Homeworld sidesteps this as everything in the game itself is a machine, a lump of metal built to be functional rather than beautiful, and for which it doesn't matter if they're entirely made out of fl at edges, and the recesses in their skin are textured on instead of being built into the 3D mesh.

Shape of things to come

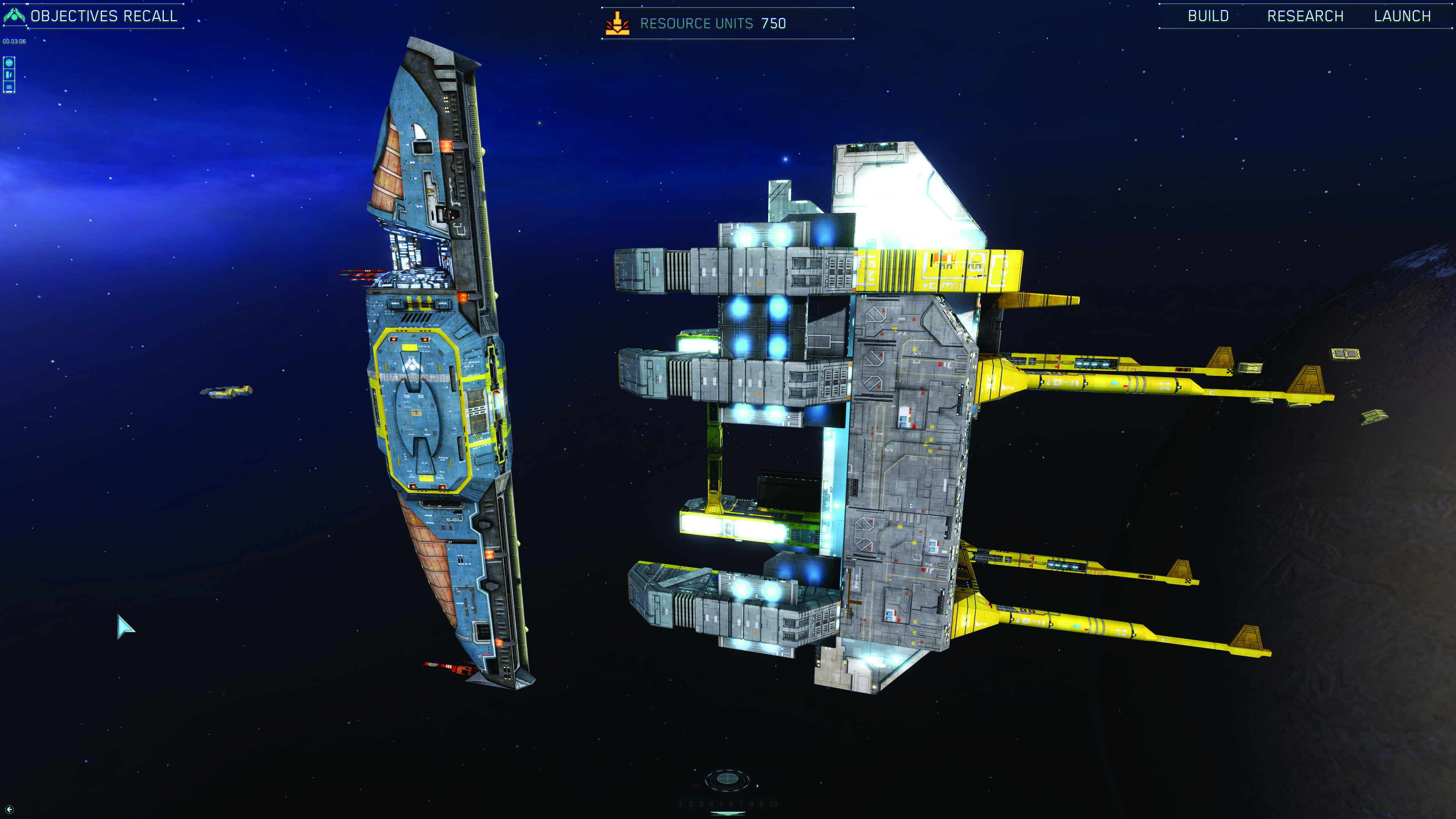

Take the Kushan mothership, aka the Pride of Hiigara. It has no need to fly in an atmosphere, so it doesn't need wings or a sleek aerodynamic form. It could have been an orbiting car park, the Pompidou Centre or a school gym block. But its designers chose to make it a space banana, an interstellar almond croissant, or perhaps a boomerang—apt considering the way it goes out then comes back in the first few missions. It's a distinctive piece of design that rightfully made it to the cover art for the game. In my memory it's bright yellow, but appears grey in the remastered game, with yellow highlights around the docking bay and what appear to be sections of wood panelling, though they might just be advanced space materials.

The continued interest in the series that’s led to Homeworld 3 means it has never really left the collective PC gaming consciousness.

This shape also plays a role in the game. Despite being 3D, missions generally play out in a flat 2D plane, and your vertical home is easily recognised among the trails of fighters and the lances of beam frigates. Attack ships on fire are a common sight in Homeworld, but the trails they leave behind as they travel are another key part of its visual appeal. Not only do they help you to zero in on ships that might just be a point against the star field, but they allow you to differentiate between friends and enemies too.

The continued interest in the series that's led to Homeworld 3 means it has never really left the collective PC gaming consciousness. The remastered edition did so much to make a classic playable again, and was much needed, but nine years after its release it's beginning to show its age, and a new Homeworld, full of the things that make gaming great today, feels fitting for a series now clocking up a quarter-century.