Tim Schafer likes Star Wars. But as far as he’s concerned, Lucasfilm’s video games were the company’s greatest creative output. In the early ’80s, George Lucas’ burgeoning computer division explored a few forms of entertainment outside of the movie industry. In 1984, the company released a sci-fi-inspired sports game called Ballblazer as well as a primordial first-person shooter set in space called Rescue on Fractalus! To Schafer, these games were a revelation. The video game industry, on the whole, seemed almost magical.

“I was there at the beginning,” Schafer says. “I remember my dad bringing home a Magnavox Odyssey, the first home arcade console ever and just being so fascinated with it. Sometimes it feels funny to explain to people why it’s exciting to see things moving on a screen. I’m trying to talk to my daughter about it. She’s grown up with smartphones, and I’m like, ‘No, you don’t understand. TV was controlled by other people, and then you could make dots move on it!’ It was so fascinating.”

Schafer quickly became a video game fan. He devoured text adventures such as Zork, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, and Scott Adams’ Savage Island series. After his dad brought home a few Atari consoles as well as an Atari Computer, Schafer began experimenting with designing his own games, but he didn’t initially think about pursuing a job in the video game industry. In college, Schafer studied computer science, however, he was most passionate about creative writing. Authors like Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse-Five, Breakfast of Champions) were his icons, and he dreamed of being a writer.

“I thought I would write short stories and get a job at a database programming [company],” Schafer says. “All the jobs back then were database programmers … I loved video games, but, in my head, they were made by companies. I would think of Atari as, ‘Oh, it’s this big, monolithic building full of scientists and robots and some big, massive brain.’ But I realized later, ‘Woah, they were just young kids. They were young programmers all by themselves making these games.’”

One day, a friend told Schafer that Lucasfilm Games (rebranded to LucasArts in 1990) was looking for developers who could program and write. Schafer felt that he had unknowingly been preparing for a dream job his entire life. He thought back to the days he spent playing LucasArts games on his Atari, and he knew he didn’t want to pass up this opportunity. He just had to nail the interview.

“I had a bad phone interview with David Fox [the designer and programmer behind Rescue on Fractalus! and Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders],” Schafer says. “He was really nice, but he asked me what Lucasfilm Games I had played, and I told him I really liked the games I had played on my Atari 800, like Ballblaster. He was like, ‘Ballblaster, huh? That’s what Ballblazer was called when it was pirated.’ [laughs] I was like, ‘Oh, God. He got me there because I had a disc of all their pirated games. Piracy’s bad, kids. Don’t do it. You’ll end up like me and have your own company and stuff.”

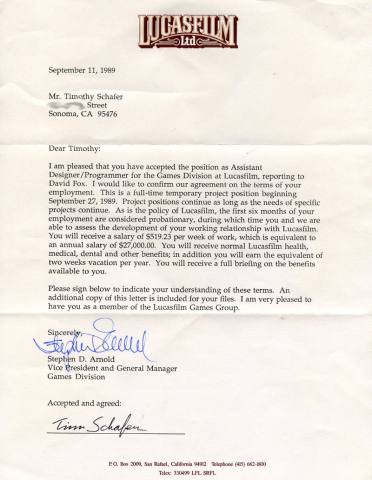

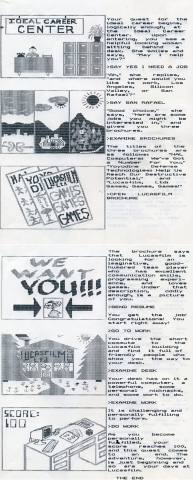

While Schafer was convinced he’d blown the initial interview, he wasn’t deterred, and spent several nights crafting a perfect cover letter/resume. In a cheeky nod to the job he hoped to one day attain, Schafer designed his letter to look like an early-’80s graphical adventure game complete with ASCII art depicting the Lucasfilm campus. Interview be damned, Schafer got the job.

A copy of Schafer’s cover letter to LucasArts, which helped him get the job

A copy of Schafer’s cover letter to LucasArts, which helped him get the jobLife On The Ranch

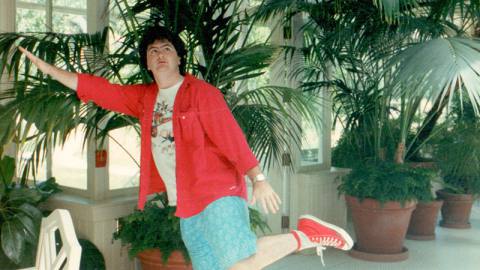

After the success of Star Wars, George Lucas built Skywalker Ranch near Nicasio, Calif., to function as his personal movie development workshop. The grounds contained an animal barn, outdoor swimming pool, fitness center, vineyard, and gardens full of fruits and vegetables for the onsite gourmet restaurant to use. When Schafer joined Lucasfilm in 1989, the campus also housed a motion picture mixing facility and served as the corporate offices for the studio’s many accountants and lawyers.

“It was amazing!” Schafer says. “I mean, right out of college, to go to work at Skywalker Ranch, you know? This was before Episode 1 was even imagined, so this was Star Wars in the magic times … there were a lot of celebrities around Skywalker Ranch. Jack Nicholson stopped by. Pearl Jam would record records there. At one point, Michael Jackson was at the Fourth of July picnic. You had to get used to like, ‘Don’t go up to people. Don’t bother them. Be cool around celebrities.’”

Schafer and his LucasArts family celebrate the release of The Secret of Monkey Island, which is still considered one of the most important adventure games of all time

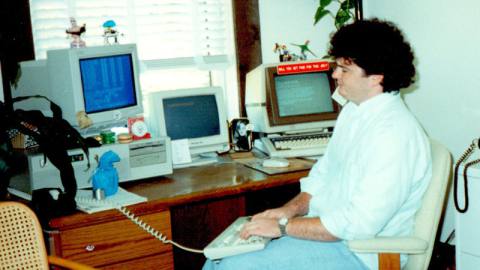

Schafer and his LucasArts family celebrate the release of The Secret of Monkey Island, which is still considered one of the most important adventure games of all timeLucasfilm’s computer and game division was tucked into the back of the Ranch’s facilities, but Schafer still found it to be a near-idyllic workspace. Over coffee breaks, he could walk out on the balcony and watch deer graze in the field. When he returned to his desk, he and his cohorts would joke around and talk about their favorite computer games. “It had a really well-funded startup kind of vibe, and then at lunch, you’d walk down to the main house, this beautiful Victorian, where there was gourmet food for $3 a day,” Schafer says.

However, Schafer’s time at the Ranch didn’t last long as some of the higher-ups at Lucasfilm eventually got fed up with the rowdy antics coming from the games team. “They kicked us out because games people do things that they don’t like at the Ranch, like ordering pizza at midnight and being a little bit rowdier,” Schafer says, laughing.

Schafer and the rest of the LucasArts team moved into the Kerner Complex in San Rafael, Calif. The building was also home to the movie special effects giant Industrial Light & Magic. At the time, ILM was working on films such as The Hunt for Red October, Back to the Future Part III, and Total Recall. The practical effects for many of these films required a lot of model work, and Schafer remembers watching scale figures of World War II bombers exploding outside his office windows.

Schafer in Die Hard 2

Schafer in Die Hard 2“Fun things would happen,” Schafer says. “They’d be like, ‘Hey, anyone wanna be an extra? It pays 50 bucks. You’ll be an extra in Die Hard 2.’ We ran out there [at] 11 at night to 3 in the morning and just walked around this field with fake snow. They filmed us walking in different directions and put potato flakes on our shoulders.”

Schafer’s time at LucasArts was unforgettable, but it wasn’t all fun and games. He had been hired to complete some serious work … work that also involved a lot of fun and games. As it would turn out, Schafer’s creative output over the next several years would result in some of the most beloved adventure games of all time.

Monkeying Around

Before Schafer joined LucasArts, George Lucas had licensed the Star Wars video games to companies like Atari. This meant Lucas’ own employees couldn’t produce games connected to the company’s massive blockbuster franchise. “They’re like, ‘You guys have to just make up stuff; we can’t do Star Wars,’” Schafer says. “It was this golden age of having access to a big chunk of George’s money and just being told to make up stuff from scratch.”

Star Wars games may have been off the table, but that suited Schafer just fine; he was more excited by the prospect of working on strange, original ideas. As soon as Schafer started, he met a brilliant young designer named Ron Gilbert who was already working on a point-and-click adventure game called Mutiny on Monkey Island – later retitled The Secret of Monkey Island. Schafer joined the team, spending days researching serious pirate lore and reading books like Treasure Island to get into the right headspace. However, when Gilbert asked Schafer to write dialogue for the game, Schafer hesitated. Instead, he wrote a couple of jokes about a three-headed monkey, which got a laugh out of fellow game designer Dave Grossman.

“I was like, ‘Later, Ron will come up and he’ll write the real dialogue, which will be serious pirate lore,’” Schafer says. “And then Ron came up and he played it, he’s like, ‘Oh, that’s funny.’ I was like, ‘I’ll put something serious in there later.’ And he [goes], ‘No, that’s the dialogue. That’s the dialogue for the game.’ I was like, ‘You’re gonna leave the three-headed monkey line in there?’ He goes, ‘Yeah. And you know what? We should get [LucasArts artist] Steve Purcell to draw a three-headed monkey and put it back there.’ I was like, ‘Are you kidding?’ I was terrified that this raw, silly joke was going in there.

“I still had that image in my head of the big building full of scientists and robots that made games, like some super smart brain that knows what they’re doing. And then you get in it and you realize everyone’s just like you. People are smarter than you, for sure, but not like a different species of smart. So yeah, I didn’t think the game would be super serious, but I thought it would be, I don’t know, I thought some adult was going to come along and write the real dialogue.”

Later, when the team was designing combat for Monkey Island, Schafer felt like they hit a wall. Early concepts were based on Jordan Mechner’s fighting game Karateka and featured high, low, and medium attacks that players could counter using high, low, and medium blocks. The team even spent time watching several classic Errol Flynn films for inspiration. However, the group never felt like the sword-fighting mechanics were a good fit for their adventure game. Gilbert eventually had the revelation that the dueling mechanic should be based on a war of words where players chose snappy comebacks and insults as a way of attacking their opponent.

“I was like, ‘You can’t – people want to swordfight! They’re gonna be so mad,’” Schafer says. “I was so scared by this crazy idea, and then, of course, it turned out to be that the insult sword fighting is some people’s favorite part of Monkey Island, and it’s this classic thing. That was another example of just how afraid you are sometimes of ideas that don’t fit. Learning to run with them was an important lesson.”

After working on The Secret of Monkey Island and Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge, Schafer moved into the role of co-director, alongside Dave Grossman. The two created Day of the Tentacle, a bizarre adventure game about a group of young friends and their time-traveling adventure to stop a sentient, disembodied tentacle from taking over the world.

“I used to talk about Day of the Tentacle as being the last fun game to work on,” Schafer says. “I always liked the games after, but that was the last time it felt easy because we didn’t have 3D and we didn’t do voice … The brainstorming sessions were so fun because we’d just spend all afternoon in a room eating candy and telling jokes and accidentally designing a couple puzzles a day. Those were really fun.”

Many of the jokes in Schafer’s early LucasArts adventure games came about as the team goofed off in their office, trying to make each other laugh

Many of the jokes in Schafer’s early LucasArts adventure games came about as the team goofed off in their office, trying to make each other laughSchafer became the lone director on his next project, Full Throttle. LucasArts hoped Full Throttle would revolutionize the adventure game genre, and Schafer had the freedom to craft a more serious story about near-future biker gangs and corporate espionage. Schafer and his team moved into the offices that once housed Pixar and got to work modernizing their traditionally convoluted mechanics into a streamlined point-and-click interface. At one point, Schafer designed an interactive sequence where Full Throttle’s protagonist underwent a peyote-induced hallucination. This sequence was cut from the game, but some of its concepts eventually took shape in the Psychonauts series.

Around this time, Schafer also continued to refine his writing style and prove himself as more than just a humorist. Where The Secret of Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle were off-the-wall cartoons, games like Full Throttle featured unique, detailed worlds full of compelling characters. Schafer began to understand that he could tell funny stories that still had heart and said something meaningful. Of course, as any artist will tell you, creating anything of value is hard.

Grim Fandango

Grim Fandango“There are lot of writers that have shot themselves; I think I know why,” Schafer says. “And that’s probably something I should learn [to deal with] better, because [writing] can be really isolating … When you do something creative, it’s one thing to just output your own creative ideas, but to be able to explain them, why you’re doing it – I’m not even clear why I’m doing half the stuff I’m doing. It’s hard to sit in a room and be like, ‘I think the reason I’m making this joke here is that three-headed monkeys are funny.’ And what if someone was like, ‘I think it should be a four-headed monkey!’ Being able to have that conversation is a skill that people have to learn.”

After Full Throttle, Schafer worked on a film noir-inspired adventure called Grim Fandango, which followed a travel agent for the dead named Manny Calavera on a multi-year journey across the underworld. Like Full Throttle, Schafer hoped to expand the definition of an adventure game. Grim Fandango combined Aztec beliefs of the afterlife with a 1930s Art Deco aesthetic to produce an incredibly striking visual style. The game’s environments were built using a mix of pre-rendered 2D backgrounds and 3D character models, which allowed the team to design new kinds of puzzles that encouraged players to explore the world. When Grim Fandango launched in October 1998, it received rave reviews and a few “Game of the Year” nods. Schafer didn’t know it at the time, but it would be his last project with LucasArts.

Under The Shadow Of Star Wars

In the mid-’90s, the rights to Star Wars games had reverted to LucasArts, and by the turn of the millennium the company was ramping up production on a series of games to support the release of the Star Wars prequel films. Schafer watched the tide at Lucasfilm turn from supporting original ideas to focusing on expanding a singular science-fantasy universe. While Full Throttle and Grim Fandango had been critical darlings, their market value couldn’t compete with one of the biggest media franchises on the planet.

“Some people in management really didn’t like the adventure games because they were not huge money-makers,” Schafer says. “Especially once they started making Star Wars games … They were like, ‘Hey, Tim, after Grim, why don’t you just make a PS2 game?’ That was their code for some sort of actiony kind of game. And I kind of wanted to, too. ‘Yeah, sure. I’ll make a console game. I’ll take all of the things we know from adventure games – the dialogue and story and characters and stuff – but it’ll just be easier to use and interact with.’”

Throughout the ’90s, Schafer played Super Mario 64, Final Fantasy VII, and the original Tomb Raider games. Those experiences awakened an excitement in him to explore fully-realized 3D worlds. Inspired by those titles, he began work on a spy-themed game that was a mix of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the ’70s spy thriller Three Days of the Condor, and the Hong Kong wire-fu movies of Jet Li. Schafer continued to play with the idea of letting players travel deeper into their minds to meditate on objects to progress the story – circling concepts that would finally see the light of day in Psychonauts years later.

Schafer has hosted the Game Developers Choice Awards a number of times during his career. He also received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the organization in 2018

Schafer has hosted the Game Developers Choice Awards a number of times during his career. He also received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the organization in 2018However, after a year of prototyping this space-age spy game, Schafer felt like it was time to move on from the company that had given him a career. He wanted more flexibility over his company culture and the freedom to pursue any project that sparked his imagination. If he’d stayed much longer at LucasArts, he might have been asked to create a Star Wars or Indiana Jones game, which could have been fun, but he didn’t feel like he had the appropriate skills to play in someone else’s world.

“Making up a world from scratch is one set of skills, and working with someone else’s world is a different set of skills … Before [Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace] shipped, licensing was like, ‘These characters can’t have lightsabers; they’re not Jedi.’ [That team] was like, ‘What? We made all these characters have lightsabers!’ They ended up having billy clubs or something. At the last minute, they had to turn off the lights on the lightsabers. If I licensed Psychonauts to someone else, I’d be the same way. I’d be like, ‘That’s a psychic power, you can’t have magic! The difference between psychic powers and magic is rah rah rah rah.’ I’d be exactly the same way because when you make a world you want it to be consistent.”

Schafer and actor Jack Black during a promotional tour for Double Fine’s Brütal Legend

Schafer and actor Jack Black during a promotional tour for Double Fine’s Brütal LegendIn the summer of 2000, Schafer left LucasArts and founded Double Fine Productions which has achieved its own measure of fame over the years. Still, many fans look back with reverence at the work Schafer produced during the first decade of his career. Titles like The Secret of Monkey Island, Day of the Tentacle, and Grim Fandango are still considered some of the best adventure games of all time. Even so, Schafer recognizes that the most important thing he developed during his time at LucasArts wasn’t an impressive gameography, it was the formative experiences that shaped him into a designer who could lead a team.

“Something I learned at Lucas was that you don’t really place your bets on ideas, you place your bets on people,” Schafer says. “It’s not the strength of the game idea that makes the game successful, it’s the people who are going to push it, make it work, and change the idea.”

This article originally appeared in Issue 336 of Game Informer.