A zombified Maximus — Russell Crowe’s Roman warrior from Ridley Scott’s 2000 Oscar winner Gladiator — straightens his tie while looking into a bathroom mirror in the Pentagon in modern-day Washington, D.C. Then he exits the room and prepares to embark on his next mission, in an endless cycle of violence stretching back to ancient Rome. Thus ends the infamous script for a Gladiator follow-up that will never get made — especially now that the conventional-by-comparison sequel, Gladiator II, actually exists.

A quarter of a century after Ridley Scott’s swords-and-sandals epic made more than $450 million at the box office and won Best Picture (and four other Academy Awards), the saga of Maximus Decimus Meridius has returned to theaters. But while Gladiator II follows Maximus’ son Lucius (Paul Mescal) on a familiar quest to win his freedom, get revenge, and change Rome for the better by way of the Colosseum, there was a moment in the mid-2000s when Scott, Crowe, and Australian alternative rocker Nick Cave tried to take the franchise in a radically different direction.

In a 2013 interview with Marc Maron, Cave revealed how all of this came about. After the success of the original movie, Universal Pictures wanted a sequel. But while Scott’s initial plan was to tell a new story with new characters in that same world (a logical choice, given that his hero and villain are both dead by the film’s end), Crowe was keen to return to the role that won him his first Oscar, so he asked Cave to help out.

This wasn’t quite as strange a request as it seems. Yes, Cave is best known as the frontman for the rock band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, but he also wrote the 2005 film The Proposition, an Australian Western that earned widely positive reviews. Fresh off that success, a Hollywood career seemed like an attainable goal for Cave.

Regardless of who wrote the script, however, the real problem was figuring out how to bring Maximus back from the dead. “That’s where it all went wrong,” Cave told Maron, recalling a blunt conversation that apparently went like this:

Nick Cave: “Hey, Russell, didn’t you die in Gladiator 1?“

Russell Crowe: “Yeah, you sort that out.”

So Cave did… sort of.

His screenplay (subtitled Christ Killer) has become the stuff of legends. The bizarre yet captivating script starts in the afterlife, sends Maximus back to Rome as an undead warrior, and ultimately ends with a centuries-spanning war montage in which Crowe fights his way through the Crusades, World War II, and Vietnam. “I enjoyed writing it very much because I knew on every level that it was never going to get made,” Cave told Maron.

You can read the entire 103-page treatment for yourself online, but you probably have better things to do. So here’s a recap.

Gladiator 2: Christ Killer opens in the Underworld, a desolate afterlife full of human suffering and endless rain. (Cave describes it as a “sodden wilderness.”) Maximus soon meets a guide, Mordecai, who brings him to a crumbling temple where the Roman gods hold court.

Cave imagines the gods as decrepit, petty old men who’ve lost their power due to the rise of Christianity. They send Maximus on a mission to kill one troublesome god, Hephaestos, who’s rallying support for Christianity. If the assassination mission succeeds, they claim they’ll reunite Maximus with his dead wife and son. But the heretical deity tricks our hero and sends him back to the world of the living. Maximus is suddenly transported through space and time, arriving in France 17 years after the events of Gladiator.

Maximus’ resurrection is one of the script’s most dramatic moments, with Russell Crowe rising out of the body of a dying man, right into the middle of a skirmish between Roman soldiers and Christian rebels. In a 2017 interview, Scott explained the logic behind this resurrection, telling a YouTuber that Maximus could travel through “the portal of a dying warrior” to come back to life.

That’s never made clear in the script, but Mordecai does reveal that the gods have banned Maximus from the afterlife for failing in his mission, rendering him immortal. “You, my friend, have angered the gods,” Mordecai says. “They have deemed you never return… to the other world.” In 2023, Crowe offered a more thematic explanation on the Happy Sad Confused podcast: “He’s killed too many people to go to heaven, but he’s too good of a man to go to hell.”

From here, Gladiator 2: Christ Killer plays out as a surprisingly straightforward and somewhat boring historical epic. Maximus heads to Rome, where his dead son has been reincarnated as an adult Christian rebel. The version of Gladiator II now in theaters retcons Lucius, the Emperor’s nephew in the original Gladiator, as Maximus’ son, but that doesn’t happen in Cave’s script. In his version, Lucius is the villain — a Roman general determined to snuff out Christianity.

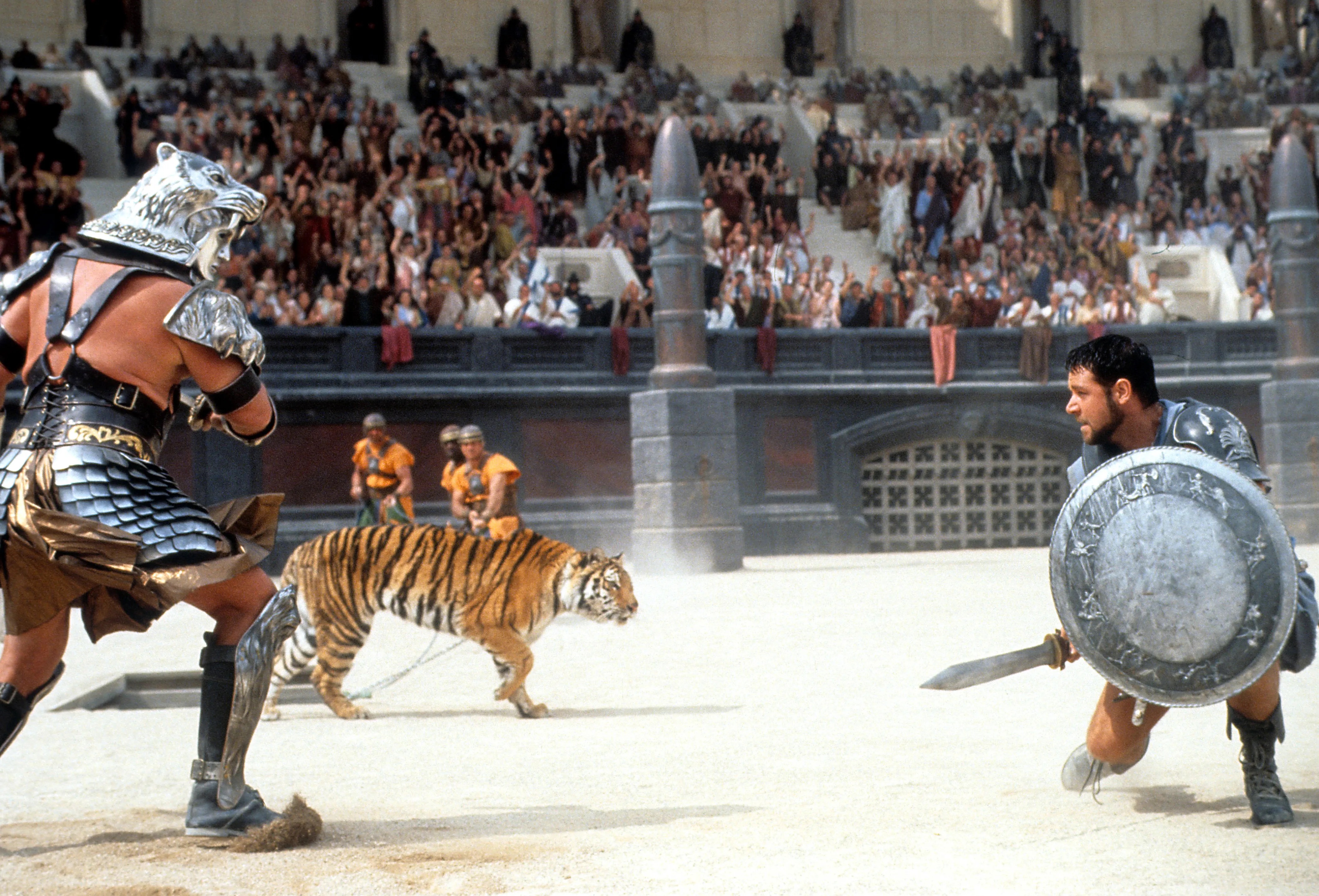

Both versions of the film emphasize civil unrest, but while Cave’s script devotes many scenes to the Christians living in Rome and their fight to survive, Ridley Scott’s 2024 sequel — written by Napoleon screenwriter David Scarpa — continuously tells us the Roman people are unhappy, but never really shows us why. Scott and Scarpa’s movie gives audiences what they enthused about from the first movie, however: Colosseum battles and plenty of them, with the first one taking place within the film’s opening hour, followed by several more.

By comparison, Cave’s script takes 81 minutes to get to the arena, and then only for one brief scene. Both screenwriters flood the Colosseum for a historically accurate naval battle, but neither can resist adding animals that never would have been present. (Scott fills the waters with deadly sharks; Cave opts for “100 alligators.”)

Ultimately, the biggest problem with Cave’s script is that it doesn’t make much use of its core concept. Zombie Maximus is a creative idea with endless possibilities, but apart from one early scene where he strolls through a plague-ridden town on the way to Rome, his immortality doesn’t matter much to the plot until the end of the story. (Maximus has always been a killing machine, and making him undead doesn’t change that.)

While Scott’s sequel climaxes in a rousing Lucius speech that stops a war before it can start and restores peace to Rome, Cave chose to end his script in mass bloodshed. His version of Lucius sends an army to the woods where the surviving Christians are hiding, which leads to a violent battle.

As the dust settles, Nick Cave finally reveals his mind-boggling twist. A series of scenes show Maximus trudging endlessly through history, fighting in the Crusades, World War II, and Vietnam. Each battle is depicted in a single vignette, creating a montage of warfare somewhat similar to the opening credits of X-Men Origins: Wolverine. (The Vietnam War gets just four words in Cave’s script: “Jungle. Carnage. Choppers. Flamethrowers.”)

The action carries Maximus from ancient Rome to modern-day America. It’s unclear why he ultimately winds up at the Pentagon, working for the U.S. military, but the implication is that after Vietnam, he was enlisted into some sort of top-secret special-ops unit. It ends with that tie-adjustment moment, as Maximus looks at himself in the Pentagon mirror — then turns to find Mordecai behind him. He greets him with “Ah, Mordecai,” and Mordecai responds, “Yes, Maximus. Until eternity itself has said its prayers.”

Maximus doesn’t respond to this odd gibe — he returns to a Pentagon briefing room, where he apologizes to the assembled men for the interruption, sits down with a laptop, and tells them, “Now, where were we?” Roll credits.

When Cave presented the script to Crowe, the conversation went about how you’d expect (again, via that Marc Maron interview):

Russell Crowe: “Don’t like it, mate.”

Nick Cave: “What about the end?”

Russell Crowe: “Don’t like it, mate.”

And yet despite the absurdity of Cave’s script, there’s a powerful idea at its core. In turning Maximus into a Christian hero (both in Rome and later in the Crusades), the script appears to be drawing a line between religion and some of the deadliest conflicts in human history. It’s a dark message, especially compared to the more uplifting ending Scott offers in Gladiator II, in which Lucius embraces the dream of a Roman republic — the same idea that fueled his non-zombie father. But beneath that dream, Scott’s story still accepts that violence (both in and out of the Colosseum) is integral to any sort of change in the face of imperial power.

Then again, maybe we’re giving Gladiator 2: Christ Killer a smidge too much credit. After all, even Cave himself has admitted he had no real intention of turning his script into a movie.

“The last thing I ever wanted to get involved with is Hollywood,” he told Variety in 2006. “It’s a waste of fucking time, and I have a lot to do.”