All this week we’re looking back on the best of the Dragon Age series, to celebrate its 15th anniversary. We’ve got loads of great Dragon Age opinions and retrospectives, and we’ll be adding more to the list in the days to come.

The Mage’s Tower section in Dragon Age: Origins is already quite the marathon: Four floors of labyrinthine halls stuffed with demons and fleshy growths on the walls, with side quests and classico BioWare moral quandaries (let a guy have his soul stolen by a sex demon, or kill them both?) galore. But three quarters of the way through, it also has one of the most breathtaking roadblocks I’ve ever seen in an RPG.

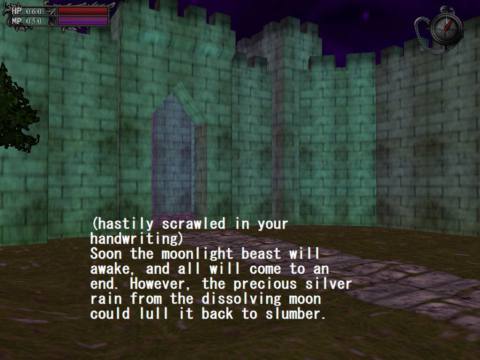

A real nasty ugly guy who looks like he got lost on his way to Scorn forces you to take a nap, bringing all the momentum of the Broken Circle quest to a grinding halt in favor of an hour-plus digression into surreal solo puzzle-solving. Everyone hates The Fade: Lost in Dreams, but you know what? There’s nothing else like it in the Dragon Age series.

Sleepy time

Dragon Age: Origins’ strengths are character writing and tactical group combat, so of course The Fade sequence has you exploring completely solo and in contemplative silence. Your jaunts into companion dreams are some genuinely great explorations of their respective characters, but they serve as these brief blasts of fresh air before your head gets held down for yet more surreal dissociation.

The zone consists of an archipelago of floating islands in Dragon Age’s sickly yellow-green dream world, with the discrete areas connected by warp points. You have to scurry about, defeating the guardians of your companions’ dreams to unlock their respective cutscenes and recruit their help for the final battle against Sloth, the demon who trapped you here. The big twist is that the islands are crammed with impassable terrain and other obstacles, requiring you to also collect four shapeshifter forms to have the full run of the place:

- Mouse form to squeeze into holes.

- Spirit form to get past force fields (sorry, “spirit doors”).

- Burning Man to

microdose hallucinogens and be annoyingwalk unharmed through flaming rooms. - Golem form to break through barriers.

My overriding memories of first going through The Fade in 2010 are of frustration and feeling lost: Pushing through promising paths only to find obstacles I didn’t have the form for yet, muddling through solo combat encounters, and generally just wishing I could get back to the main plot. A mod to skip the section entirely (save the companion scenes and big fight at the end) has remained one of the most popular Origins addons at the Nexus for 14 years.

Sickos yes

And yet, I find myself having this fascination and nostalgia for The Fade: Lost in Dreams. Maybe I’ve played one too many incomprehensible indie horror games at this point, but there is something genuinely dreamlike and unsettling about the much-maligned exploration and puzzle solving in this sequence that really speaks to me.

Looking at the Fade’s appearances in later Dragon Ages, it might as well be a layer of Hell from D&D or something: Just a nasty place where demons come from and big, high level plot points happen. Lost in Dreams’ isolating exploration amid such a strange implementation of familiar Dragon Age assets has this almost vaporwave quality that I find myself digging more and more as years pass. It’s more a really experimental, fan-made Dragon Age mod, but it’s part of the official game.

The Fade: Lost in Dreams really feels like it should have been cut, this vestigial digression that kills all the momentum of its parent questline, and that makes it even more interesting. Surely the one-off shapeshifting mechanic and companion dreams were somebody’s (maybe multiple somebodies’) darlings, not quite fitting in anywhere else, but too dear to get rid of.

For better and for worse, you just wouldn’t see this kind of thing in a game of Origins’ scale and profile nowadays: Too many developers working on it, too much money riding on its success, a more pressing and established drive toward flow and approachability. That makes sense, it’s not any kind of moral or artistic failing, but it’s why I think I’ll always cherish Origins’ weird little hour-long tumor of a dream sequence.