It was a secret the entire gaming world had been privy to for nearly two decades, but Resident Evil director Shinji Mikami would only admit to it in an October 2014 interview with the daily newspaper Le Monde: his most celebrated work, one that would go on to spawn a new, wildly popular genre, had been heavily inspired by French horror adventure Alone in the Dark. Without it, he conceded, his landmark survival-horror game would probably have ended up as a first-person shooter.

Even that belated confession, focusing mainly on visual design—perspective and camera placement—rather downplayed the similarities between the two legendary horror titles, from the zombie-infested mansion setting to the choice of an underpowered protagonist, and from the awkward tank controls to the memorable scenes featuring window-crashing hellhounds. One can trace earlier precursors to survival horror: Project Firestart on the Commodore 64 and Capcom’s own Sweet Home on the NES. But Alone in the Dark, published in 1992 by an ailing Infogrames, became the first game to provide the complete template for the genre, lacking nothing save a world-conquering platform like the PlayStation to anticipate Resident Evil’s seismic impact.

Still, inspiring one of the most popular franchises in gaming history and sparking the emergence of a subgenre that defined two successive console generations in the late 1990s and early 2000s was hardly the extent of Alone in the Dark’s influence. Perhaps less overtly, the progenitor of survival horror has guided the evolution of the medium in two other ways since its release 32 years ago.

The rise of cosmic horror

Horror subgenres, from the invasion movies of the 1950s to the millennial zombie mania, are inextricably tied to our sociopolitical anxieties. It’s not hard to see how in an increasingly precarious world, one where we’re increasingly aware of our daily existence being shaped by faceless powers we can neither understand nor control—from a global economy in constant upheaval to the whims of social media platforms—Lovecraftian horror has been elevated to a dominant mode of expression. Nevertheless, the emergence of a subgenre requires a catalyst, a work that compellingly introduces its core themes. Zombies needed Resident Evil and The House of the Dead in 1996; gaming’s era of cosmic horror was ushered in less conspicuously, as befits the genre, four years earlier by Alone in the Dark.

There were a few scattered precursors, naturally: Gary Musgrave’s Kadath, written for the obscure Altair 8800 home computer in 1979; Infocom’s first foray into spooky territory with The Lurking Horror in 1987; and the flawed, wildly ambitious The Hound of Shadow, published by a then-adventurous Electronic Arts in 1989. But Alone in the Dark was the first Lovecraftian game which forced the industry to take note: winning awards, pioneering new design techniques, and becoming a huge crossover success in the process.

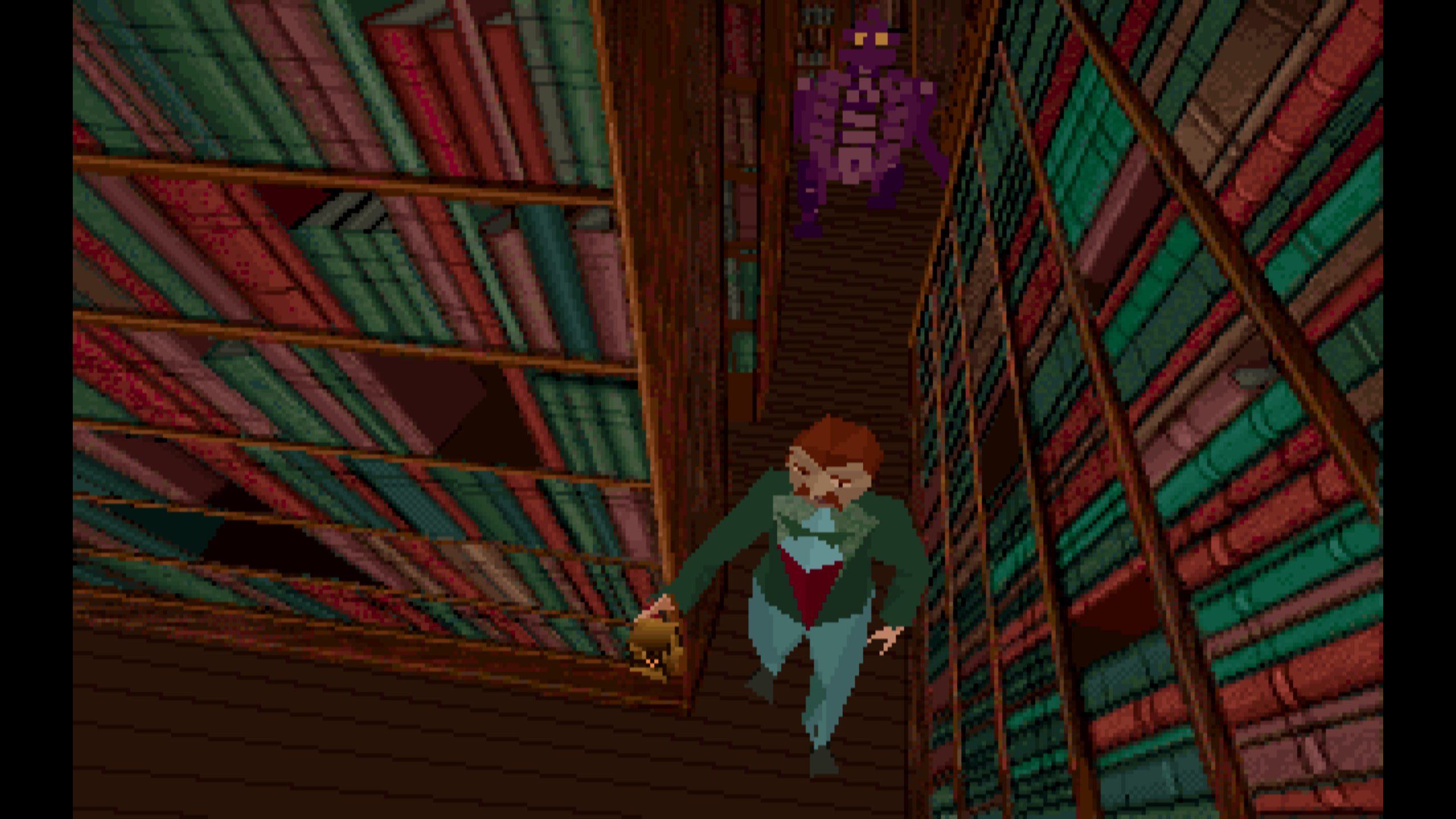

Practically every hallmark of cosmic horror was present within the walls of the Derceto mansion, not least its Prohibition-era, Deep-South setting. Its lobbies and ballrooms are guarded by strange extraplanar entities. The shelves of its library are laden with tomes bursting with forbidden knowledge. A sinister ritual to unleash chaos upon an unsuspecting world is the undying villain’s sole motive. Most characteristically (and most unusually, at the time, for an action game), its protagonist’s eventual triumph comes not through brute force but through careful investigation and piecing together, clue by clue, the manor’s dark history.

In the wake of Alone in the Dark’s spectacular success (shifting more than half a million copies in the limited PC market of the era), Lovecraftian themes started to proliferate. First, with Infogrames own follow-ups (developed as tie-ins with Chaosium’s tabletop role-playing system, Call of Cthulhu), Shadow of the Comet and Prisoner of Ice, then at slowly but steadily increasing rates, out of which arose the occasional gloomy classic: Anchorhead, Eternal Darkness, Sherlock Holmes: The Awakened, Dark Corners of the Earth.

And in the last decade or so, cosmic horror has become ubiquitous in gaming. A quick search of the keyword “Lovecraftian” on Steam yields nearly 1500 results, more than thirty of which were released this February alone. The theme has become so all-pervasive, it can be encountered in genres that are not typically associated with horror—from action RPGs like Bloodborne, to turn-based roguelikes like Darkest Dungeon.

New ways of seeing; new ways of playing

Glancing back at Alone in the Dark’s most accomplished Lovecraftian predecessors (including the three titles mentioned a few paragraphs earlier), one makes an intriguing observation: all of them were text adventures. Games had been drawing from horror movies since the mid-1970s (with Jaws, then the Alien franchise being especially popular sources of inspiration during these formative years) but had trouble finding ways of actually scaring the player in the 8- and 16-bit eras. Cosmic horror in particular, with its glacial pace and frail protagonists, was an obvious mismatch for the platformers and shoot ‘em ups that dominated the market in the 1980s. If a Lovecraftian game were to exist—one that did not rely on the the typed commands and obstinate parsers of interactive fiction—a paradigm shift was needed. Alone in the Dark provided that.

Even today, playing that unforgettable opening sequence in Derceto’s creepy attic, it remains striking how convincingly the game immerses you into your character’s plight and how organically it channels your thoughts into meaningful action. The first time that infernal cur smashes through the window, you’re likely to die but, after a quick reload, it becomes obvious how the creature’s access can be blocked by moving a nearby upright piano in front of the pane. A bulky chest can be similarly dragged above a trapdoor, barring entry to the zombie set to emerge soon thereafter. And all of these complex interactions are taking place in real-time, within a fully-realised 3D environment without the player being required to type a single verb.

Nicolas Deneschau, author of the just-released series retrospective Les dossiers Alone in the Dark : Aux origines du Survival Horror, narrates an early demonstration of the game at the Infogrames offices in Villeurbanne, as recounted by members of the developing team: “[W]e have these two journalists facing a single PC and the whole team behind them, including a very stressed Frédérick Raynal. Several witnesses told me, when they saw the logo (the armadillo) moving in 3D, they raised an eyebrow. But when they were able to manipulate the character in the attic and step back with a natural gait, one of the two testers literally fell out of his chair. They kept exclaiming ‘We can shoot!!! We can go back!!!’ It was crazy.”

While 3D environments were nothing new and, in fact, becoming something of an industry-wide trend in 1992 with both Wolfenstein 3D and Ultima Underworld releasing in the same year, Alone in the Dark’s fixed perspective guided the eye and exploited the player’s anxiety in unprecedented ways with its strategic camera placement. Moreover, its range of possible interactions (owing something to those earlier text-adventures or, perhaps, to its tabletop RPG associations), offered a different proposal for engaging with a gameworld, one that prioritised thought and careful observation and emphasised storytelling over either Wolfenstein’s action or Ultima Underworld’s exploration. Whether as private investigator Edward Carnby or concerned niece Emily Hartwood, Alone in the Dark’s players were encouraged to navigate and manipulate their environment in realistic, rational ways, dive into Derceto’s secret history, and become involved into an overarching narrative which unfolded with the kind of complexity hitherto reserved for text adventures and point ‘n clicks.

A couple of misguided sequels churned out in haste to capitalise on the original’s success, a forgettable film adaptation, and two fascinating but flawed attempts at a reboot mean the original Alone in the Dark is remembered more as the game that inspired Shinji Mikami than for its own considerable accomplishments. Among the numerous Silent Hill and Resident Evil homages, it’s disappointing to note that there are so few contemporary titles directly referencing Infogrames’ trailblazing classic (I have managed to locate only two, both of them well worth a look for series veterans: The Padre and A Room Beyond). Still, with a third attempt at resurrecting Alone in the Dark set to be released in a few days, this might be the perfect moment to climb the stairs to Derceto’s attic once again and, in the process, rediscover one of gaming horror’s underappreciated gems.