“Who is Final Fantasy for these days?” is a question without an obvious answer, but it’s one that its developer and publisher, Square Enix, must reckon with all the same. Both Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth and Final Fantasy 16 failed to meet sales expectations according to Square’s financial report from September, which created a whirlwind of takes on why that was, and what Final Fantasy’s future could or should look like.

I don’t have the crystal ball I’d need to tell you which of those takes are right or wrong. What does seem clear is that the era of Final Fantasy as the Japanese role-playing game series that most people are thinking of when the genre comes up—the one with a grip on games culture that’s a guaranteed sales bonanza—is at an end.

That’s not to say no new Final Fantasy will sell and sell and sell, but the last 15 years have shown that it is, more often than not, selling a few million copies per game rather than 10 million-plus, like Final Fantasy 15 managed. Which would mean that the issue with Final Fantasy has at least as much to do with Square’s expectations for it as those of either its fans or potential fans.

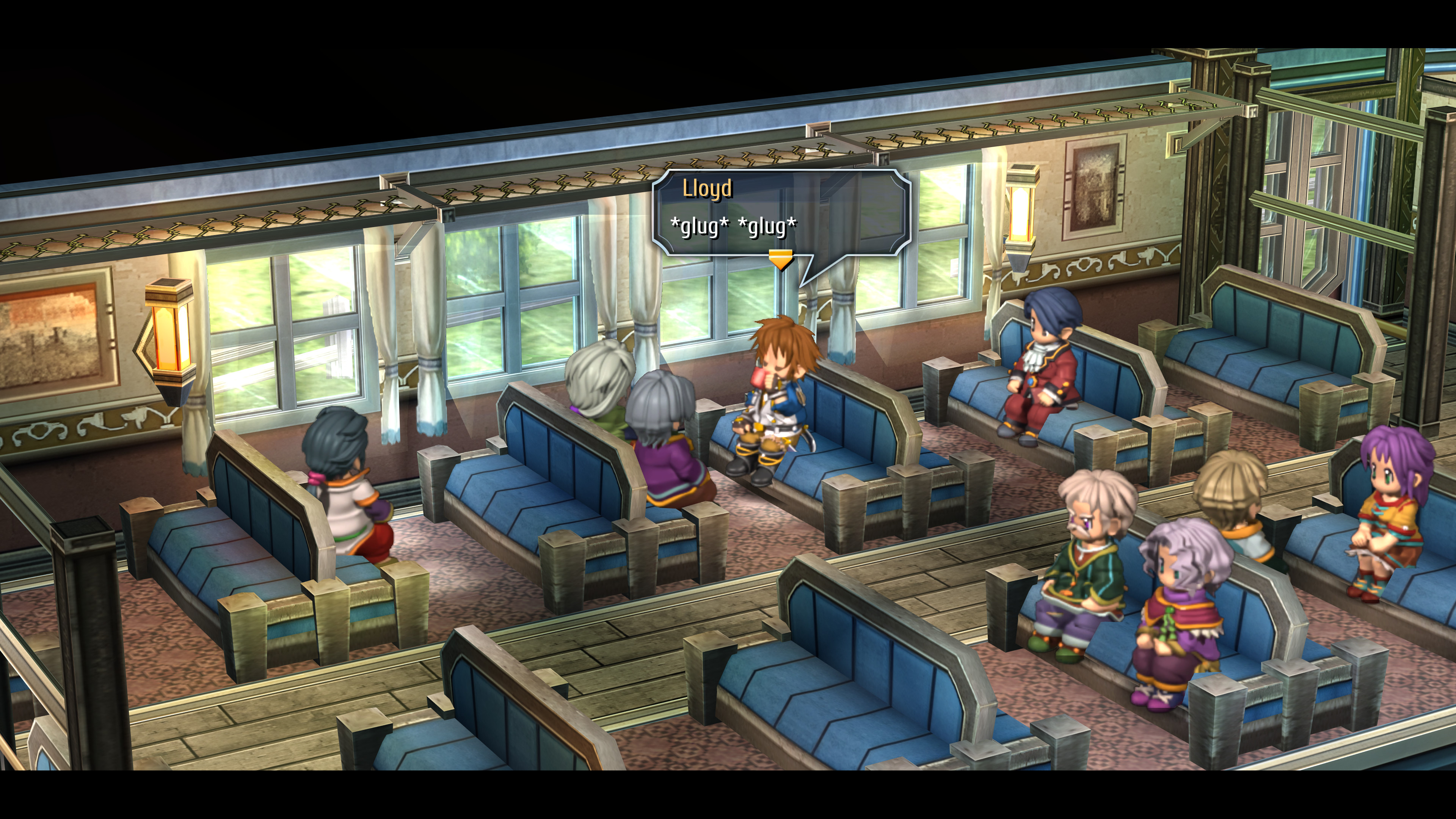

Despite this, Japanese roleplaying games are thriving. Nihon Falcom never had the massive international breakout of Square nor Enix back in the 1980s or ‘90s, but the company is seeing unprecedented success in the present with its tentpole franchise, Trails, owing to the growth in the series’ popularity outside of Japan. In a 2024 interview, Falcom president Toshihiro Kondo declared that 60 percent of its sales are now international, and the rate at which the company publicly celebrates another 500,000 or million in Trails sales has risen exponentially in recent years.

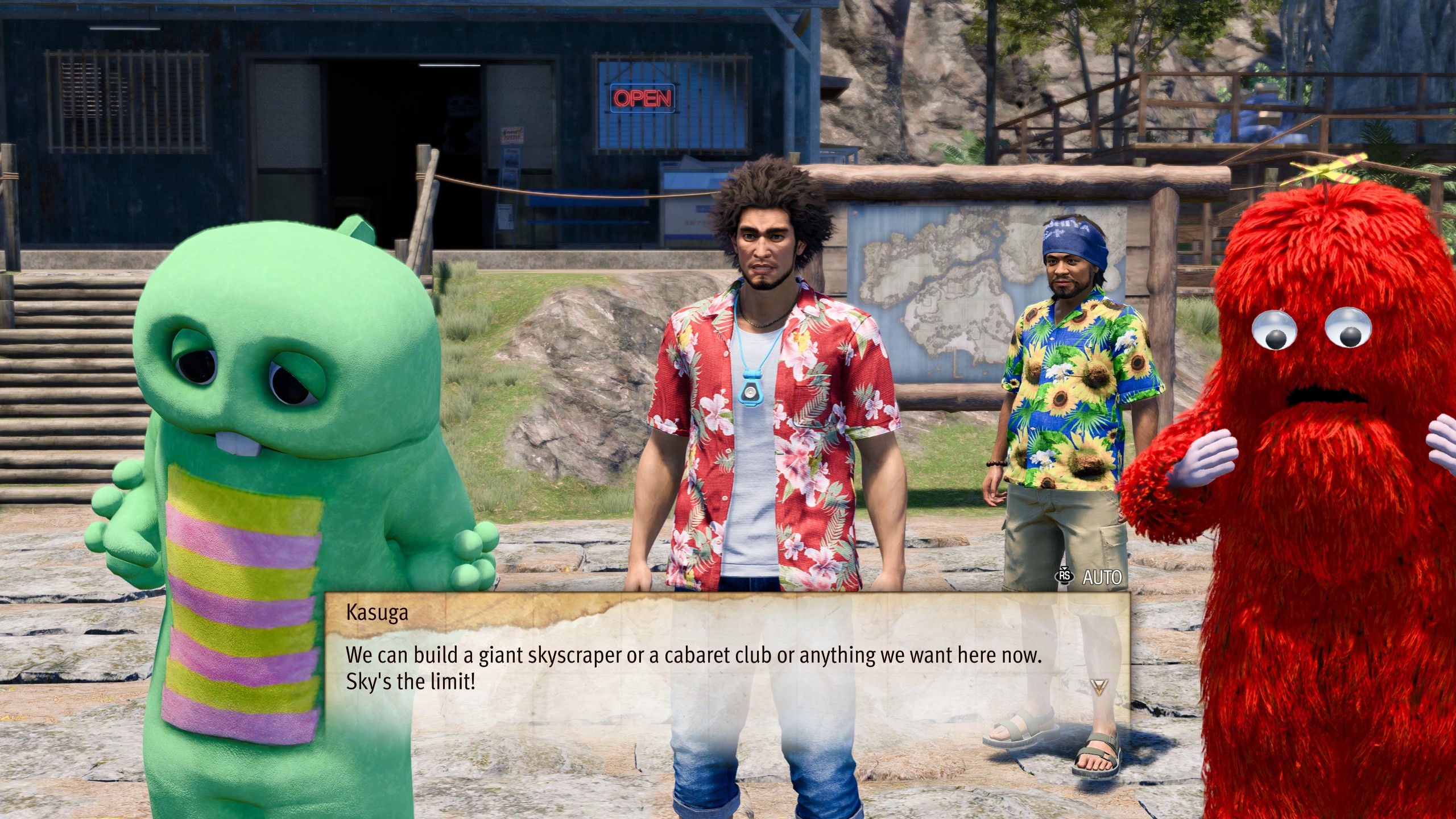

Similarly, Atlus’ Persona series used to sell just a few hundred thousand copies each, but Persona 5 has become an institution unto itself—with over 12 million sales between its various releases and spin-offs. Sega switched its long-running Yakuza (now Like a Dragon) games from beat ‘em up adventures to full-on RPGs more akin to Dragon Quest. They’ve only become more popular since those changes. And Dragon Quest itself just outsold every other 2024 game in Japan in one week with a 2D remake.

JRPGs are doing very well indeed, even if elements of the genre are now more ubiquitous than the genre itself. As has been pointed out elsewhere, part of what made Final Fantasy stand out at its peak was that JRPGs weren’t as widely accepted as they are now: many of the games you think of as classics weren’t selling like Final Fantasy, or selling at all, or only sold well in Japan but released to crickets internationally.

Final Fantasy managed to be cutting edge with its storytelling, with its visuals, with its tendency to experiment and forcibly evolve the genre in a way that broke through to the mainstream more regularly than any other RPG franchise out of Japan.

Final Fantasy is still experimenting. Square is still putting together stunning graphics. But this isn’t the ‘90s or early 2000s. The first six Final Fantasy games were released between 1987 and 1994. The PlayStation had three in four years. Since then the escalating cost and length of development for each new entry has meant fewer games that take forever to make, and the evolution part isn’t happening so much either, Final Fantasy begins to play more and more like other popular games that already exist in order to maintain mainstream attention.

And the story part? Well. Let’s just say for brevity’s sake that opinions are divided.

Meanwhile, Nihon Falcom’s pumping out Trails game after Trails game despite massive scripts, interconnected storytelling that resembles fantasy novels more than games, and huge worlds full of depth. There have been 13 of them in the series’ first 20 years—or, in the same stretch that Final Fantasy got from FF12 to FF16. Like a Dragon is switching back-and-forth between action spin-offs and its much lengthier mainline RPGs, never leaving fans wanting or waiting for the next ridiculous adventure.

One of the open secrets here is Falcom and Sega’s comfort with reusing assets and locations with each game. No one is going to criticize the production values of the Like a Dragon games, which look amazing and have obvious effort and care put into them, and the Trails RPGs have certainly seen some boosts to production value recently as well. Both franchises, however, are happy to return to old art and game structures, leaving plenty of development time and budget to focus on what’s new and justifies another trip down familiar roads. It’s a real ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ situation.

You know what you’re getting into when you start a Like a Dragon game, or a Trails, or a Dragon Quest, or a Persona. You can enthusiastically explain exactly what these games are to someone showing a hint of interest.

Trails isn’t going to outsell Final Fantasy, no, but it’s not budgeted to do that, and neither is Like a Dragon. Neither fails to evolve or grow. 2024’s Trails through Daybreak actually mixes action RPG elements into its turn-based setup for a new strategic blend that will also be used in the upcoming Trails in the Sky remake.

But in the same way a Dragon Quest game is always clearly a Dragon Quest game or an Atlus RPG is an Atlus RPG, they’re telling different and new stories with changing mechanics. The balance of consistency with new ideas has fostered smaller, but very dedicated, fanbases for both that have their publishers thrilled, their expectations met or even exceeded.

It’s hard to see the same clear lineage or consistency with modern Final Fantasy. Square titled a kinda-sequel reimagining of a beloved game “Remake” for meta wordplay reasons and made it the first of three “remakes,” all of which have drastically different gameplay from the original. And that’s is fine! But expectations should be better set for that sort of project. There are a few reasons the middle game of the trilogy might not sell as well as the first one: People falling off due to the game playing so differently from the original, or the “remake” only being 2/3 finished, or the dramatic shift towards an Ubisoft-esque open world experience.

As with Final Fantasy 16, PlayStation 5 exclusivity didn’t help matters. It’s no surprise that Square is planning simultaneous multiplatform strategies from hereon out. But that still doesn’t solve the identity crisis, one worsened by FF16’s switch to outright action RPG.

Final Fantasy is not what it once was, culturally, but it can still be there from a quality perspective. Square needs to take a lesson from the thriving franchises around it and figure out just what Final Fantasy is supposed to be, like Falcom has with Trails, like Sega has with Like a Dragon. Each of their sequels push their respective envelopes without betraying expectations, and are available on less powerful hardware—even Yakuza has made its way to Nintendo’s aging Switch, a good sign for the series’ future on the Switch’s successor and PC handhelds.

Maybe Final Fantasy doesn’t need to be as big a production as it used to be—to reflect the fact that it is, as a phenomenon, not as big as it used to be. And it doesn’t have to be that kind of phenomenon just to get people to pay attention now.

Maybe that change would better define the series and who is even interested in it, all while allowing room for the experimentation that helped make Final Fantasy what it was in the first place.