This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 391 in December 2023, as part of our Reinstall series. Every month we load up a beloved classic—and find out whether it holds up to our modern gaming sensibilities.

Quake 2 has a fascinating legacy. Released only 18 months after Quake in December 1997, it was quickly celebrated as the best game ever made. And I mean the best. PC Gamer awarded it a score of 96, only the second game in the magazine's history to receive such a dizzying number. A technological marvel, it offered a far more focused adventure than the original's dimension-hopping escapades, with a distinctive setting and consistent enemy design. It even had something id co-founder John Carmack had previously dismissed as superfluous to a good shooter: a plot.

Over time, however, Quake 2's reputation has diminished. The following year, its narrative ambitions were superseded by Half-Life, which told a better story in a more interesting fashion. More recently, critics have pointed out that its shooting experience is flatter and more sluggish than the 1996 original, while its setting and level design lack the same weirdness and imagination. David Szymanski, creator of the retro-shooter DUSK, has described Quake 2 as “the worst id game”.

In the wake of Nightdive Studios' recent remaster, which overhauls Quake 2 for modern machines, the debate over the significance of id's sequel has arisen once more. But the remaster also provides a chance to reappraise Quake 2. What's interesting is not which of these two viewpoints is correct, but how both are equally supported by the game.

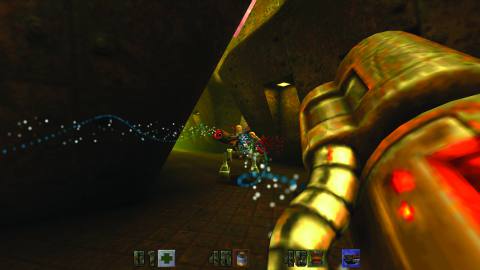

Whatever Quake 2's own ambiguities, there's no questioning the brilliance of Nightdive's work remastering it. Not only has Nightdive updated the game to make the best of modern PCs, supporting 4K resolutions, widescreens, enhanced multiplayer support and more, it also supports your ideal version of Quake 2. The remaster supports a whole host of visual modernisations like bloom lighting, dynamic shadows, antialiasing, and enhanced character models. Alternatively, you can turn all this off, switch on CRT simulation and play like it's Christmas Day 1997.

Flexible makeover

It's a wonderful, flexible makeover, and its improvements do help communicate some of what made Quake 2 such a phenomenon at the time. First and foremost are The Strogg, Quake 2's twisted cyborg adversaries. Quake 2's overarching function of space marines fighting a race of alien cyborgs may feel a little tired after two decades of similarly plotted games, but the Strogg's dilapidated, ad-hoc cybernetics that resemble the result of catapulting a body into a scrapheap, help the game maintain some flavour of its own.

Indeed, one of the toughest challenges in FPS design is creating enemies that are both imaginative in presentation, but also satisfying to fight. With the Strogg, id struck a perfect balance, giving players recognisably humanoid enemies, but with countless variations that all behave in different ways. Taking on a melee-focussed Berserker presents a substantially different challenge from dodging the shoulder-rockets of a heavily armoured Tank. Some enemies I'd completely forgotten about, like the Mutant, one of the few opponents that isn't a cyborg, and the Brains, a particularly unnerving cyborg that answers the question “What if WALL-E got infected by John Carpenter's The Thing?”

But the Strogg's most notable characteristic is how reactive they are to damage. Blast a guard onto the ground with your shotgun, and they might take one last potshot at you as they expire. Shoot the head off one of the bulky enforcers, and they spray the area wildly with their chaingun arm before collapsing. These detailed animations represented a huge step forward in 1997, and the feature that struck me as the most noticeable step forward when I first played it around its original release. Even today, few shooters afford their cannon fodder such bespoke, imaginative deaths.

These grisly ends don't exist in isolation, either. One of the more striking things about returning to Quake 2 is just how horrible the Strogg world is. This is clear enough in its desolated, brown environments and the Strogg's brutal approach to creating new cyborgs, mercilessly chopping up humans with sawblades and lasers. You can imagine the overwhelming smell of iron oxide as your press through rusting facilities smeared with the blood of your fellow marines. But it isn't the sights or scents of Stroggos that lingers in your mind, it's the sound. The compressed screams of Berserkers as they die, the shuddering moans of your imprisoned comrades turned mad through torture, the buzzing fl ies that surround a Strogg corpse after it's laid for a while in the alien sun. Quake 2 isn't a scary game, but its monstrously unpleasant world can be thoroughly unsettling.

While the Strogg remains a compelling foe, Quake 2's arsenal has aged less well. A few of the weapons still hold up. The super shotgun rightly earns its name, packing a double-barrelled blast that will put a serious dent in most Strogg armour. Quake 2 also introduces the series' defining weapon, the railgun. Quake 3's railgun may be more famous for enabling multiplayer frags, but the corkscrew trajectory of Quake 2's slugs gives the older game's iteration a more distinctive appearance. Gibbing multiple guards with a single slug also never ceases to thrill.

Most of the other weapons, however, are either slightly or seriously underpowered. The chaingun and hyperblaster are both effective at shredding enemies into strogghetti, but they'd equally benefit from extra kick. The machine gun is still limper than a three-legged possum, while the shotgun is so ephemeral that you're never inclined to use it once you acquire its sibling.

Quake 2’s greatest weakness, however, is its level design.

Quake 2's greatest weakness, however, is its level design. With the sequel, id Software wanted to create a more believable world than previous id games, with object oriented levels that designed as recognisable, functional places. Unlike previous id games, many of these levels are connected together to form Units, with you often travelling to and from a central hub level to several side-maps where secondary objectives are completed. The Jail unit, for example, includes a Detention Centre where prisoners are held, a Guard House that serves as the Strogg barracks, and the Torture Chamber is self-explanatory.

It's fascinating just how precisely Quake 2 straddles the line between the classic mazes of Quake and the more 'realistic' approach of Half-Life. You can almost see the transition happening as you prowl the game's many gun-metal corridors. Unfortunately, id's attempt to hammer the abstractions of classic FPS design into something more grounded results in many of levels looking quite samey. They're still fun spaces to navigate, and there are a few areas that stick in the mind, but for each one there are ten brown warehouses filled with brown crates.

Fundamentals

The limitations of Quake 2's maps becomes more apparent when you boot up the remaster's new episode, Call of the Machine. Developed by Wolfenstein: The New Order creators MachineGames, Call of the Machine takes Quake 2's fundamentals and uses them to build more elaborate levels stuffed with challenging set pieces. Instead of encountering one or two enemies in every corridor, MachineGames build roomier, more arena-like environments where you'll battle dozens of foes, all carefully selected to press you in new and interesting ways.

Admittedly, MachineGames has a significant advantage in today's more permissive technology. Some of the levels in Call of the Machine would have brought the average PC to its knees back in 1997. But Call of the Machine also much better understands how to build encounters around specific weapons or enemy types. In particular, Call of the Machine is a railgunner's delight, regularly funnelling you through tight corridors stuffed with weaker enemies just desperate to be gibbed, or placing Gunners on distant, elevated platforms that require a precisely planted slug to take down.

Call of the Machine is intense and frenetic in a way Quake 2's campaign rarely is. Yet while not entirely successful, Quake 2's Units are nonetheless an important landmark in FPS design. Half-Life is often characterised as a revolutionary moment in the history of the shooter, a completely unanticipated event that shook the whole industry. But Quake 2 shows the ideas Half-Life executed so brilliantly were very much in the water at the time. Quake 2 might not thread together its levels in a contiguous way. But it nonetheless succeeds in making Stroggos feel like a specific and coherent place, one that has grimly logical reasoning behind its form and function.

And while the game's premise is trite by today's standards, the execution still holds up in a lot of ways. The satellite-view briefing cutscenes that fill the gap between missions, presumably influenced by Westwood's work on Command & Conquer, are a great way of contextualising your progression without getting in the way of the action. Similarly, the framing of your adventure around specific objectives, rather than simply finding your way to the end of the maze, effectively communicates your role in undermining the Strogg war effort. Although you only ever glimpse the broader war around you, you nonetheless feel like part of something greater than yourself.

Quake 2 felt tangible, believable in a way no shooter ever had before.

Rather than being a singular event, Valve's shooter was just another step down a path that games like Quake 2 and Duke Nukem were already traversing. In that context, it's much easier to see where Quake 2's exuberant reception came from. Its reactive enemies, its more narrative driven campaign, its interconnected levels designed to resemble a place, all of these were significant advancements in FPS design.

Quake 2 felt tangible, believable in a way no shooter ever had before. Nobody was to know that something even more realistic lurked beneath the deserts of New Mexico, ready to be unleashed a year later. Today, Quake 2 might represent an intriguing evolutionary link between Quake and Half-Life. But for a few months in the rapidly changing development scene of the 1990s, it was the most advanced shooter anyone had ever made.