We live in a landscape where words like “reboot” and “retcon” are common knowledge. Hollywood executives use the word “multiverse” in complete seriousness. No one can talk about “Batman in the movies” anymore — you have to specify. Nolan Batman? Snyder Batman? Reeves Batman? Bryan Singer’s Magneto, or the First Class one? Raimi Spider-Man or the Amazing run or the MCU version? Superhero movies don’t have to explain comics anymore. They can just be like comics — places for creative folks to drop in, do their take on a long-established character, and see what the audience thinks about it.

The gift this era has given me, as a comics fan and a critic, is a new thought experiment: What would I think of this superhero movie if it had been a comic book? Did the movie find something insightful to say about a decades-old character? Did it play well in the space, relative to all the other stories that have gone before it?

I think Matt Reeves’ The Batman might actually have been even better as a 12-issue alt-universe miniseries, giving its characters more time to breathe in a new variation on Gotham. On the other hand, the original Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse has so much to say about Spider-Man’s themes of responsibility and identity, and it’s also so inventive with the form of the animated film that converting it into a comic would definitely rob it of some of its magic.

But this year, I found my experiment running aground when considering Todd Phillips’ Joker duology. Setting aside my own problems with Phillips’ writing and directing, did these two movies — which reimagine the Joker as the alternately pathetic and dangerous failed comedian turned successful murderer Arthur Fleck — have something to say about the iconic supervillain? And how did that statement measure up against the comics themselves? With Joker: Folie à Deux now streaming on Max, it seemed like a good time to reconsider the question.

And here’s my conclusion: Todd Phillips’ Joker movies don’t have anything to say about Joker comics, because they are simply not about the character of the Joker in any recognizable way.

Who is the Joker?

The mutability of a character is a sign of its strength, but characters are not endlessly mutable. How much mutation is acceptable before a character becomes unrecognizable is a topic upon which gallons of metaphorical blood have been spilled in forums digital and in person. But I think we can agree that that line exists.

You could slowly make changes to Batman — give him guns, make him OK with killing criminals, take away his money and friends, give him a differently themed costume — and eventually he would simply become the Punisher. We can argue about exactly where the line between the two of them would be, but that line exists.

And where the Joker is concerned, I believe, that line is about his interiority.

Phillips makes a lot of changes to the Joker. His films give him a name, Arthur Fleck, and an inciting incident: getting roughed up by some corporate bros and blowing them all away. They give him mommy issues and a yearning for a romantic partner, and remove his rivalry with Batman and his context within a world of theatrical supervillains and powerful superheroes. Folie à Deux has Arthur meditate aloud on the question of “Who is Arthur Fleck?” — via a sad and profoundly delivered knock-knock joke recited during the closing argument of a trial in which he has elected to defend himself, no less.

You can make a lot of changes to the Joker, because good characters are mutable. You can remove him entirely from a setting where superheroes and villains are commonplace, or remove Batman, and therefore his rivalry with him, entirely. You can make him a silly trickster or a horrifying psychopath or a Lego man. You can give him obsessions like “getting Batman to acknowledge me” or obstacles to overcome like “accidentally committing tax evasion.”

But if you give the Joker a parsable human interiority, I would argue you’ve stopped interacting with the idea of “the Joker” in any meaningful way. I think this is the fundamental nucleus of his character, as whittled down, sharpened, and compressed to a fine point by 80 years of Joker stories and hundreds of striving creative minds.

Batman’s dark mirror

We like to say that the best supervillains are mirror reflections of their heroes, which is fun to apply to Batman and the Joker, because I don’t think there’s anyone out there who, when asked “What is the opposite of a bat?” would answer “A clown.” Dig a little deeper and you can pull some oppositions from the way they’re typically characterized: They’re equally theatrically invested in fear, but they aim it in opposite directions.

Batman is taciturn where the Joker is chatty, and dark where he’s colorful. Batman represents order, while the Joker is chaos. But careful! Batman is mutable. He’s not always frightening, grim, and lawful, and neither is the Joker always flamboyant, deadly, and philosophically chaotic.

What’s immutable about Batman is that he does what he does for extraordinarily specific reasons. His motivations are entirely known, and constantly restated to the audience. His core character trauma is infamous for how often it’s been recreated in adaptation. It’s been memed into immortality. With Spider-Man as a close second, Batman is the origin-story superhero. And so by force of the narrative Joker is the anti-origin-story villain.

We don’t know why he does what he does. It’s not even clear whether he knows. His interiority is a black box, open to embody our worst fears about man’s inhumanity to man. Titans of the genre have tried to give the Joker a motivating origin story, and none of them have succeeded in crafting one that sticks. And while we should never dismiss something as impossible just because nobody’s done it yet, I also think it behooves us to learn from history.

Even recent history would suffice: It’s hard to find a compelling emotional throughline if you can’t peek into your main character’s thoughts, but Matthew Rosenberg and Carmine Di Giandomenico’s 2022 series The Joker: The Man Who Stopped Laughing gets around that issue by featuring a main character who isn’t sure whether he’s really the Joker, or just a guy the Joker brainwashed into being a Joker decoy. Jeff Lemire and Andrea Sorrentino’s 2019 series Joker: Killer Smile, meanwhile, is actually a series about the Joker’s new psychiatrist.

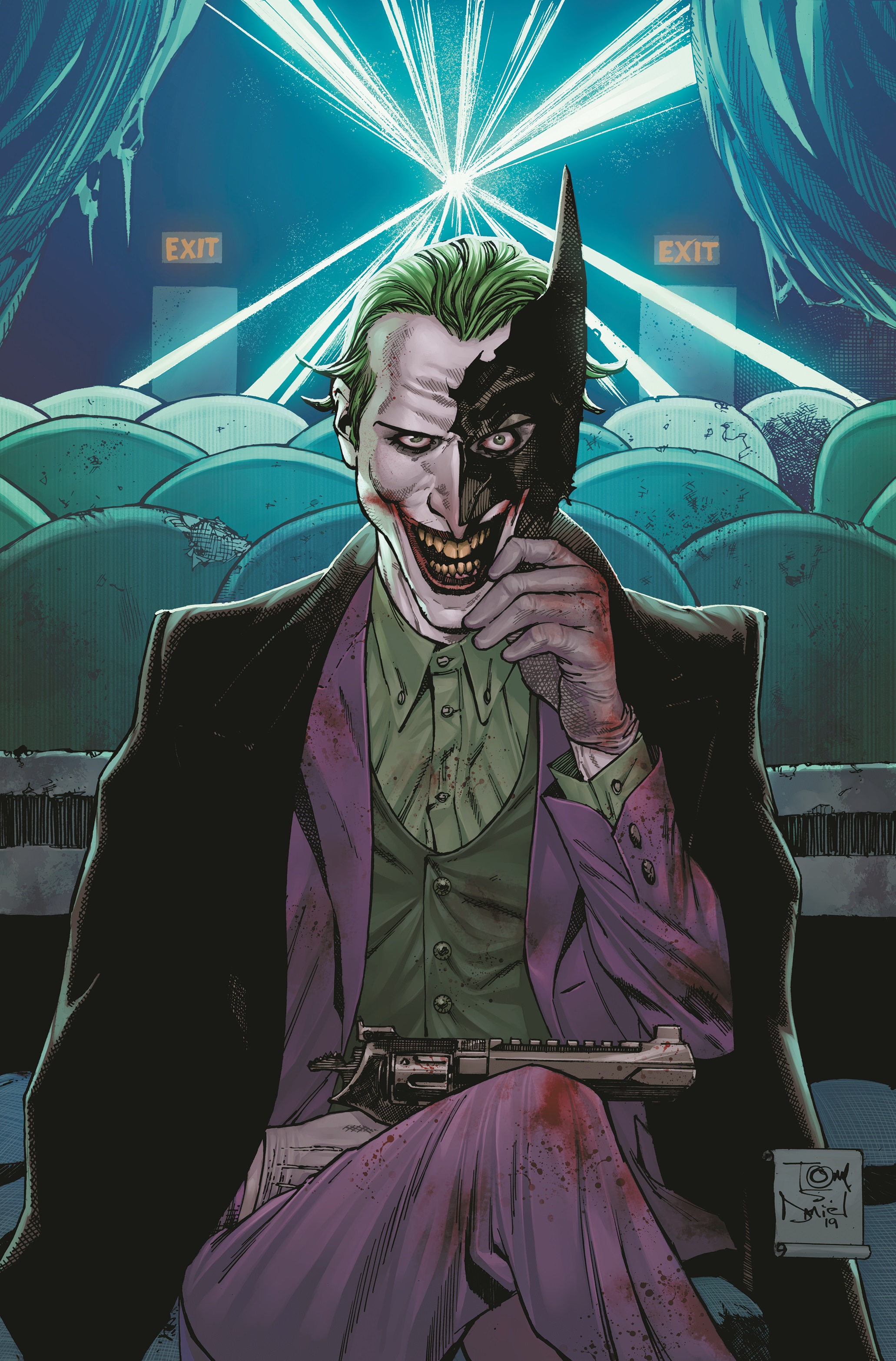

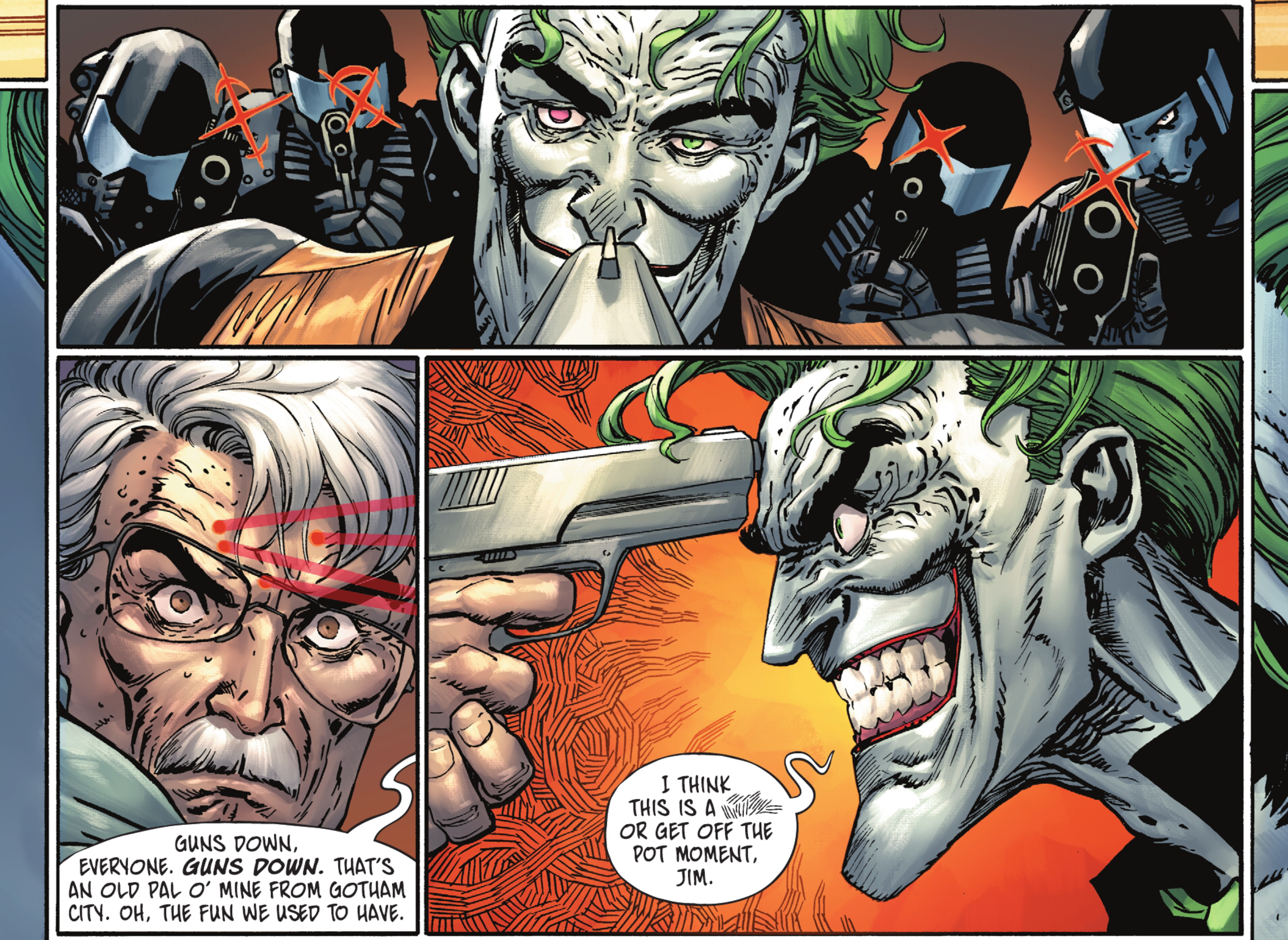

James Tynion IV and Guillem March’s 2021 Joker series tells a great story about the Clown Prince of Crime based on the extremely cogent observation that ex-police commissioner James Gordon might be the only person in Gotham City more personally wronged by the Joker than Batman. Their book features Gordon as the point-of-view character on a Catch Me If You Can-style manhunt for the Joker, wrestling with whether he should just put a bullet in the murderer for the good of humanity instead of apprehending him.

Said the Joker to the thief

This is why I struggled to apply the “Is this a good Joker story?” framework to Todd Phillips’ Joker and Joker: Folie à Deux. The Joker resists origin stories and clear motivation because they’re fundamentally opposed to the narrative purpose he fulfills as the summation of all that Batman opposes. At his most immutable, Batman is the guy who says “A senseless thing happened to me, and that’s why I have to stop more senseless things from happening.” And what has made the Joker his perfect foil is that at his most immutable, the Joker is a machine for making senseless things happen.

If you remove Batman, the character the Joker was molded around, you might still have a Joker story on your hands. And if you change the Joker so that he’s the main character of the story, you might still have a Joker story on your hands. But if you do all that and you examine who the Joker is and why he does what he does — you are simply not making a story about the Joker anymore.

And that’s fine! There are a lot of characters who are not the Joker, and I think we can agree that some of them are even quite compelling. But you’re not telling me anything salient or new about the Joker, a character honed over 80 years into a highly efficient narrative machine for making senseless things happen. You’ve made him make sense. You’ve made up a new guy for your story, and slapped Joker’s name on him.

That is, I think, what I most want to explain to any creative who, like Phillips, sees the superhero genre as a means to an end. I don’t just want to point out the faux pas of dismissing the work of the creators who came before you, of picking up someone else’s toys while not “playing in the space.” Not because I don’t think that’s important, but because I just think that if you’re a person who sees superhero cinema as a means to an end, you probably don’t care about being rude to comics creators.

What I want to get into the skulls of this particular kind of superhero filmmaker is that comics have already done the work. What you’re dismissing is decades of evidence of what succeeds, doesn’t succeed, or only succeeds if you do it like this. Phillips saw the Joker’s lack of an origin story as freedom to make his own take, not a sign that his origin story’s very absence, despite 80 years of opportunity to create one, was significant.

Declining to learn from decades of stories made by hardworking creatives developing the same character is rude, sure, sure. But it’s also shooting yourself in the dang foot.