Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 – The Fatalities and Fandom of the Arcade Era is an upcoming novel detailing the origin and early history of Mortal Kombat. The book compiles interviews with MK co-creator John Tobias and other designers, critics, and fans to weave a comprehensive tale of the franchises’ beginnings. Author David L. Craddock (Stay Awhile and Listen trilogy, Monsters in the Dark: The Making of X-COM: UFO Defense) has launched a Kickstarter campaign to get the book off the ground and shared an exclusive chapter from the book with Game Informer that you can read below.

Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 Book Cover

Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 Book CoverLong Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 – The Fatalities and Fandom of the Arcade Era goes behind the scenes to reveal untold stories from the making of Mortal Kombat 1 through 4 and explores how the franchise impacted popular culture, and is funding now on Kickstarter. In this excerpt from the book, a small boy earns the respect of the drug dealers who rule his arcade by besting them in a fight—in Mortal Kombat.

**

Bulgaria’s opioid crisis didn’t happen overnight. The country was part of the Soviet bloc, a totalitarian regime whose agents policed drug channels in and out of regions under their control. Residents of countries such as the United States and Europe had access to a plethora of recreational drugs, but a drug network taking root in Bulgaria was viewed as next to impossible.

That changed in 1968 when Bulgaria’s International Youth Festival allowed young people to meet attendees from other countries. They traded stories of where they lived and what they liked to do for fun. Drugs, a staple of the counterculture movement in the U.S. and abroad, were a huge part of the gathering. Still, Bulgaria avoided an epidemic until the fall of 1990. At the Hemus Hotel, located downtown in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, Iranian refugees who had fled to escape the politics of their homelands spread word that they were open for business. They were careful, operating out of locations such as the underground shopping area of the National Palace of Culture. Rates of heroin usage climbed over the next two years. In 1992, incidents involving heroin addicts soared by 31 percent as the drug spread.

As those who ran the drug market grew bolder, their dealers emerged from the underground and set up shop in more public places. Amusement parlors became prime spots to conduct business. The clientele consisted largely of children and teens who were unsupervised, and the latter group showed an interest in substances that would guarantee them a good time. The market’s reach grew as dealers worked together to trade secrets and strategies. To avoid detection by law enforcement, they stashed heroin in pockets or, bolder still, held it in their hands until they made a sale. With nothing to do between serving customers, they commandeered coin-op games until a buyer approached. Soon, they were unafraid of police intervention. Local law enforcement had no clue what was going on.

By 1993, Bulgaria’s dealers thought of themselves as kings. Anyone who game rooms knew not to approach a cabinet if local dealers were playing, usually surrounded by a coterie of toughs who were there to protect him, or push their own supplies, or both. If you weren’t there to buy drugs, the cabinets with their flashing screens may as well not exist. No one dared oppose them.

No one except a 10-year-old boy with preternatural hand-eye coordination and enough strength to tear a head free of its body.

**

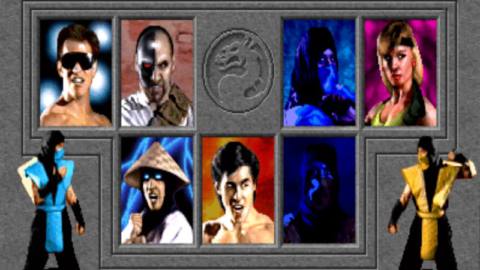

Growing up, Andrey Stefanov had zero interest in video games. He wanted to build kingdoms out of LEGO bricks. He dabbled in home games like Super Mario Bros. 3, but always returned to his bricks. Then he discovered Mortal Kombat. However, Bulgaria’s Kombat cabinet looked nothing like the hardware found across North America. Coin-op games were expensive to import, so Bulgarian operators would buy kits to install in the cabinets of older games no longer earning. “We had MK1 with a three-button layout. It was not the original arcade design; it was used in some other game,” Stefanov says.

At first, Stefanov watched older kids play Mortal Kombat and didn’t see what all the hype was all about. The graphics were great, with characters that looked more realistic compared to Street Fighter II, and the bloodshed was kind of cool. But so what? Take away the gore and it was just another punch-and-kick game. Then, at the end of a match between a ninja clad in black and yellow, and a cocky Hollywood star, the sky turned dark and the ninja peeled off his face to reveal a skull. Turning to his dazed and bloodied opponent, the ninja breathed flame and reduced the humbled star to charred bones.

“I was like, ‘That changes everything.’ The real reason for me to start playing was Scorpion’s fatality in the first game,” he says.

Every day, his parents gave Stefanov five coins for lunch at school. Every day, he made the five-minute walk to the mall near his apartment, climbed to the second floor, and ventured into the arcade where he spent his lunch money on Mortal Kombat. The game’s learning curve was steep. His three-button layout had one punch, one kick, and block. With two buttons missing, he had to do certain moves by pressing combinations of buttons such as throwing Sub-Zero’s ice by pressing down, forward, and high punch plus block.

The second and larger obstacle was the drug dealers. As Mortal Kombat‘s popularity exploded, the dealers dictated who could play. Their rules were simple: they played, and everyone else could watch or get the hell out. When they weren’t charring opponents or throwing fireballs, they stole lunch money from kids who wandered into the parlor. Some dealers knew Stefanov, so they took it easier on him. “The biggest threat I received was them taking my money for school,” he recalled.

Every now and then, the dealers let him play. The gesture was not made out of kindness. The dealer on duty would wait until Stefanov got near the end of the battle plan—an endurance match, or better yet, the fight against Goro or Shang Tsung—then insert coins, thrash Stefanov’s character, and finish the game in minutes. “It was kind of humiliating,” he admits.

Bullying was not enough to keep Stefanov away from the game room. He peeked his head in and played when the toughs weren’t around, and resigned to being chased off when one of the dealers decided it was his turn to play. Instead of running away, Stefanov hung back and picked up on strategies like punching characters out of the air and thought about how he might string moves together to form combos. One with Sub-Zero was simple: hit a jumping kick, then immediately perform his slide before his opponent landed.

Soon, a larger problem materialized. Stefanov only had so many coins. A solution materialized as a wealthy friend at school who lived in a huge house and had a Sega Mega Drive (known as Sega Genesis in the U.S.) with a copy of Mortal Kombat. “It is very different from the arcade, but you could practice on it, at least.”

Owning a Mega Drive was a status symbol. Bulgaria had been a communist country until mass demonstrations forced the government to adopt democratic reforms in the early 1990s. Part of the result was Bulgaria opening its borders to do business with foreign companies like Nintendo and Sega. Before democratic reforms were adopted, those and other game companies had no way of selling their products. That left the market open for imitators like the Terminator, a bootleg console that played Nintendo Famicom cartridges and some NES titles. Sega and Nintendo could release their 16-bit platforms in Bulgaria, but their machines proved too expensive for most consumers. Instead, most Bulgarians who had money for games bought the Terminator 2, a console with Super NES-like molding but colored black instead of beige, and only cost 23.09 Bulgarian Lev, or $13.68 in 2021 US dollars. Most games cost one Lev, or 59 cents.

Stefanov’s friend loaned him the Mega Drive and Mortal Kombat cartridge. After his family went to bed, Stefanov sat awash in the television’s glow, practicing special moves and combos. It was the first of many nights he sacrificed sleep. One morning a week later, Stefanov dressed, collected his lunch money, then skipped school and headed to the arcade. One of the dealers was hogging the cabinet. He was playing as Sub-Zero. After every win, he boasted that no one could play ice ninja better than he could. Stefanov approached and politely asked if he could challenge him. The dealer smirked and waved him forward.

At the character select screen, they both chose Sub-Zero. Two rounds later, Stefanov’s character stood over the doppelganger’s corpse, blood dripping from the severed spinal column. The dealer shot him a nasty look, then deposited more coins. This time he waited until Stefanov made his choice—Sub-Zero again—then counter-picked, a tactic where one player chooses a character based on their opponent’s choice. The dealer chose Johnny Cage, the cocky Hollywood star.

A crowd formed around them. Stefanov risked a glance at the dealer. The man’s face had gone from scarlet to puce. This was bad. Stefanov dropped his right hand from the buttons. With his left hand, he tilted the joystick one way, then the other, causing his character to pace back and forth. The dealer took the first round with Flawless Victory. The onlookers, mostly friends of the dealer’s, cheered and applauded. The dealer turned to his Stefanov wearing a smug grin. “It’s fine. You can play. I’ll beat you, anyway.”

Stefanov placed his right hand on the buttons. Within one minute, he’d won a round. Within two, he’d separated the dealer’s head and spinal column from his body again. The dealer swore and shoved Stefanov against the cabinet, slapping him again and again. Then the man stormed off. Wincing, Stefanov left the arcade.

He returned the next day. To his surprise, the dealers, including the one he’d killed twice, let him step up to the machine. This time, instead of bumping him off the cabinet or roughing him up, they asked questions. A grin split Stefanov’s face. “You had to learn to play the game so you’d be able to do well even on single-player,” he explains. “You had to learn respect to not be terrorized.“

David L. Craddock

David L. CraddockYou can support Long Live Mortal Kombat: Round 1 – The Fatalities and Fandom of the Arcade Era by visiting its Kickstarter campaign. Craddock plans to hold a Reddit AMA today at 1 p.m. Eastern to answer questions and share additional content.