In addition to our main Game of the Year Awards 2025, each member of the PC Gamer team is shining a spotlight on a game they loved this year. We’ll post new personal picks each day throughout the rest of the month. You can find them all here.

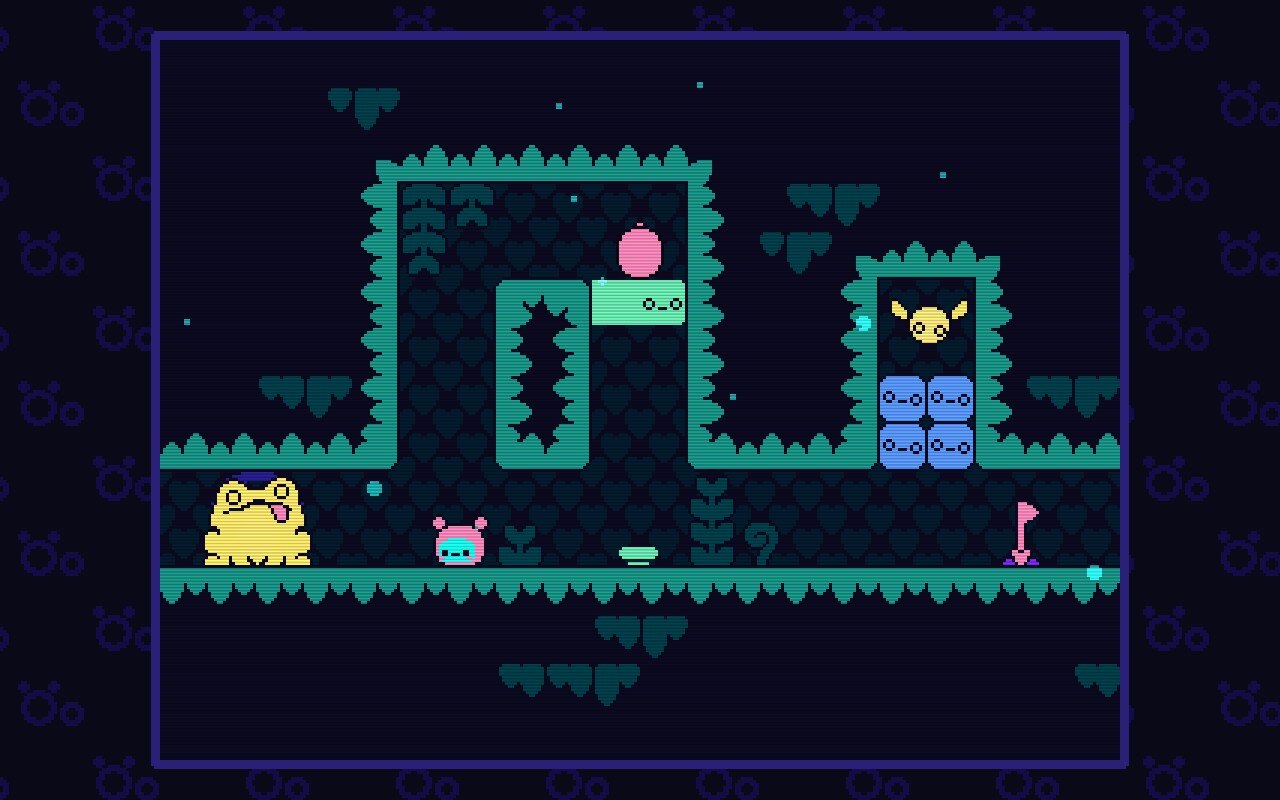

There are no words in Öoo. Even the title is a calligram: the umlauted O is our hero—the umlaut represents their ears—while the lowercase os are the bombs they carry around. In this puzzle metroidvania, the hero (let’s just call them Ö from now on) can’t really do much except explode those bombs. There is no jumping, no mantling, no attacking, no nothing, unless it can be achieved via the detonation of a bomb.

When Ö starts with one bomb things seem simple enough: to jump, I spawn a bomb beneath myself and detonate. If I place a bomb and stand to the left of it before detonating, I’ll be propelled leftward, which can be useful to clear a pit. Eventually Ö gets a second bomb, which offers a little more manoeuvrability while further complicating the puzzles.

All this points to a clever but by no means revelatory puzzle game. But Öoo is a truly impressive piece of design, mostly for the way it removes the dependable power-up driven progress structure of metroidvanias and replaces it with player knowledge. In Öoo, impassable obstacles are made passable not by a fancy new ability—like Hornet’s dash, or Samus’ Morph Ball—but with a new bomb-centric technique the game has taught me via a series of clarifying problems. And this is achieved with no text and no explanatory videos. (Not even the menus have text, resorting to glyphs instead.)

Early in this four-odd hour game I reached a confusing dead end. After all my efforts, there was nothing in this dead end for me to collect. There was a warp point, but why would I come this far just to warp backwards?

Then it clicked: during the preceding five or six screens I had learned how to get a bomb on my head. This is not a straightforward task for a legless and armless blob. The game had quietly taught me how to do it, and now I could destroy blocks that were otherwise too far above me.

The second bomb is introduced quite early on and opens up a lot of potential. One simple example: What if I need to collect an item hovering above a pit of spikes? It’s possible: place a bomb to my left and right. Detonate the left, which will propel me to the item, and then detonate the right, which will propel me back to safety.

Öoo constantly surprised me with strange new ways of approaching its two bomb toolset. For every half-dozen rooms, one would have me stumped, before I managed to find some new bombing technique that hadn’t occurred to me yet. Creator Nama Takahashi has, I feel certain, figured out every possible problem that can arise for our innocent, bomb-reliant Ö. But what’s more impressive is the amount of confidence Takahashi has in Öoo’s learning curve. If players were able to glean some of the more advanced techniques without the game’s gradual, ambient instruction, this game would be a failure: one with a pitiable 15 minute runtime.

Öoo elegantly and procedurally explores every permutation, every possible wrinkle, in its simple ‘move around with bombs’ concept, and each of its major areas brings a new overarching idea to the table. Some of the late game epiphanies had me fistpumping more than anything else I’ve played in 2025, not just for pride at having overcome the obstacle without checking Takahashi’s own walkthrough (I consulted it twice) but at the single-mindedness it must take to conceive it.

After playing Öoo I browsed the Steam forums and found some speculation that there might have been a third bomb planned but ultimately scrapped. I can totally understand why Takahashi might have abandoned that third bomb, if he had ever intended it in the first place: the complexity would be unmanageable. The sheer number of problems a third bomb could bring to the table is potentially endless. And since it’s not Takahashi’s style to leave problems on the table, it’s probably for the best that we only got two.