In front of me are two VR headsets. They’re practically identical; both versions of the Pimax Crystal Super, a high-end, tethered unit. Though for their near-indistinguishable appearance, they are different in one very important way: one is fitted with QLED displays, and the other, Micro OLED.

My job for the past couple of days has been to switch between the two headsets. Trying one, then the other, and back again, until my eyes hurt. I’ve tested a range of games, carried out a selection of tests, and jotted down plenty of notes along the way. We’ll get to those, but if you want the shortened version, here it is: Micro-OLED is excellent, with a few caveats that I’ll go into greater detail about below.

The Crystal Super comes with, what Pimax calls, an optical engine. This is essentially the core of the headset and includes the lenses, screens, cooling, and even some of the tracking, including the eye-tracking sensor. A user can slide one optical engine out of a headset and replace it with another, and Pimax offers four to choose from for the Crystal Super:

Feature | Micro-OLED | 50 PPD | 57 PPD | Ultrawide |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Pixels-per-degree | 53 | 50 | 57 | 50 |

Resolution per eye | 3840 x 3552 | 3840 x 3840 | 3840 x 3840 | 3840 x 3840 |

Max. refresh rate | 90 Hz | 90 Hz | 90 Hz | 90 Hz |

Field of view | 116° horizontal | 127° horizontal | 106° horizontal | 140° horizontal |

Eye-tracking | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

All except the Micro-OLED use a QLED (LCD with Quantum Dot) panel with a Mini LED backlight, which allows for local dimming—switching on and off a small zone of the backlight to improve contrast. Every one of these optical engines is capable of displaying an impressive picture quality and with excellent brightness, but from my time with the 50 PPD and Micro-OLED options, the latter certainly takes the cake.

The Micro-OLED optical engine uses a Sony panel with a lower vertical resolution than the QLED option—presumably the Sony ECX344A with a matching resolution and 90 Hz refresh rate. The reduction is not noticeable, however, due to the second-highest pixel-per-degree (PPD) rating at 53 PPD. This is made possible by the reduced field of view, which is the second-lowest of the four.

PPD, pixel pitch, resolution, and FoV all play a part in the overall clarity of a virtual reality headset. Think of it like an image painted onto a folding fan: the wider the fan goes, the larger the image becomes, but the easier it is to spot the individual brush strokes and creases that make it up. Open the fan only three quarters of the way and the image appears to be a higher quality but you see less of it. Pimax, and other VR manufacturers, use varying lens designs to balance between overall FoV and clarity.

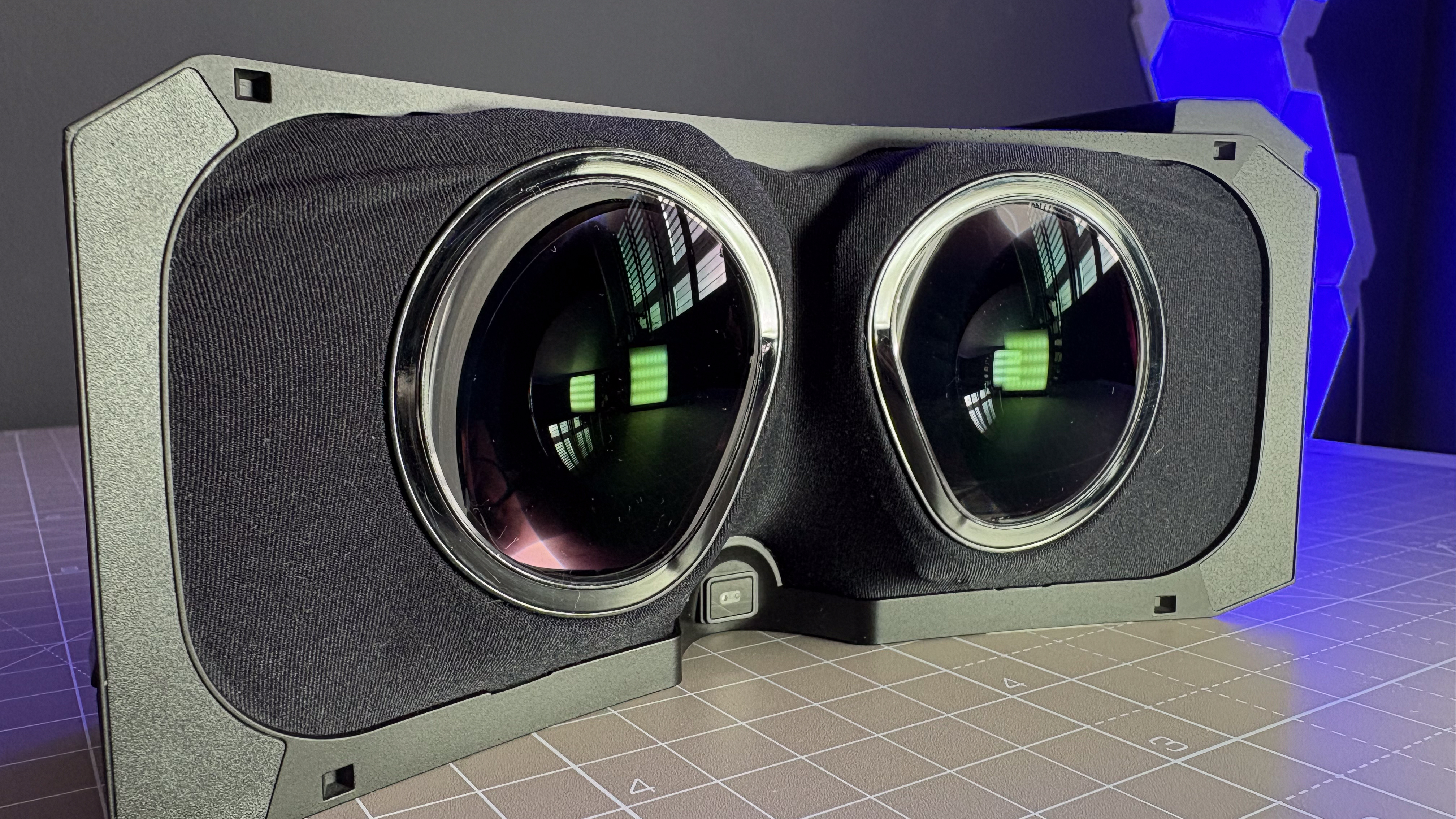

For the Micro-OLED optical engine, Pimax uses specially-designed pancake lenses. Pancake lenses require plenty of brightness—as Valve’s engineers told me when I had a go with the Steam Frame, which also uses pancake lenses. Though brightness doesn’t appear a problem with the Sony displays used on the Crystal Super. The ECX344A is rated to 1,000 cd/m2, though not all of that is making it through the pancake lenses to your eyeballs. I never thought to increase the brightness during testing, anyways, which is a good thing, as on closer inspection I already had the brightness set to 100%.

These pancake lenses are concave, which is a little different to the ever-so-slightly convex lenses I’m used to seeing with the Quest 3. I’d guess in part due to the magnification required for the tiny Micro-OLED screens.

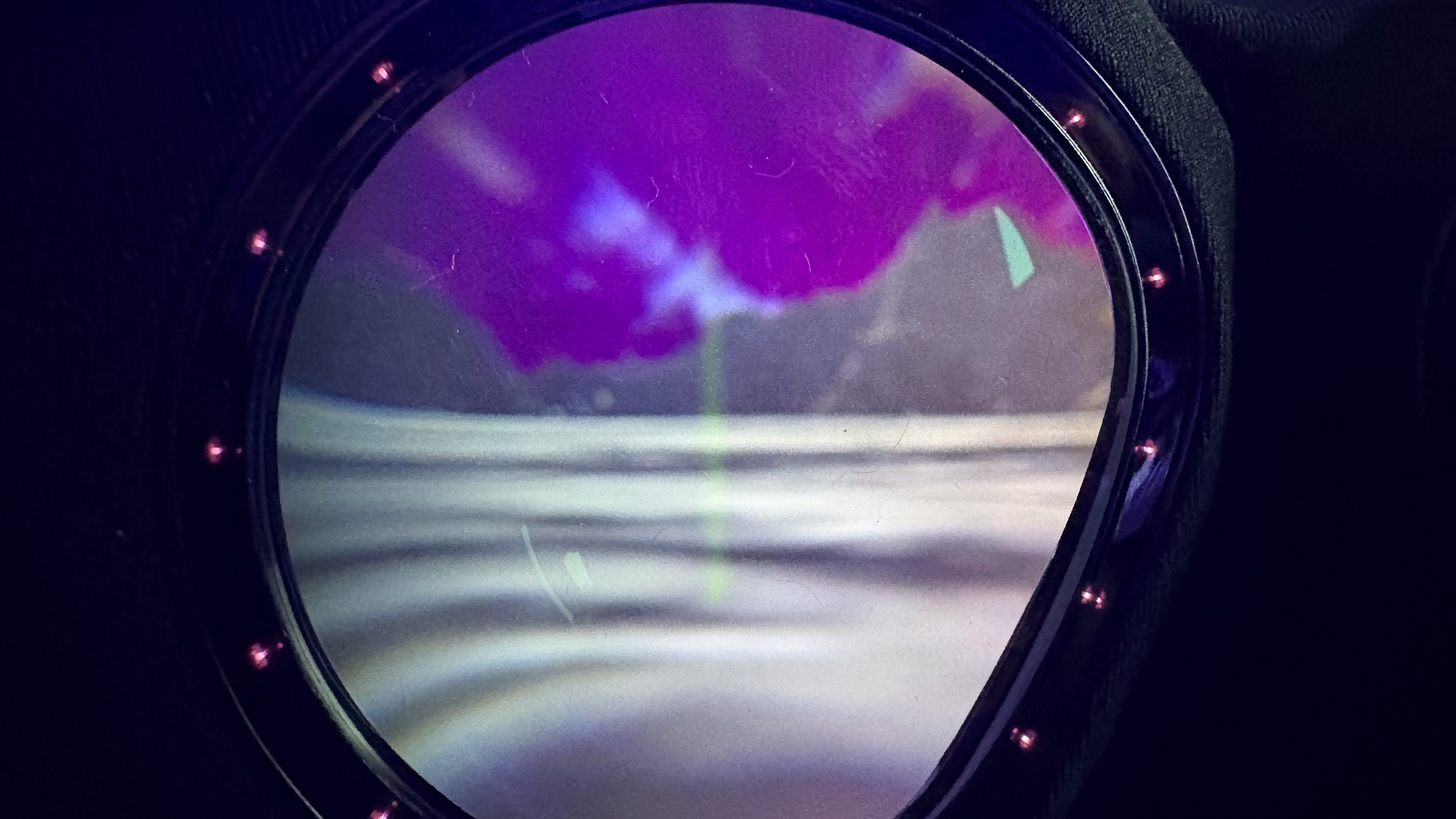

The Pimax has more glare than the Quest 3 and QLED Crystal Super, especially in tests that aim to show any glare at its worst. In practice, it’s not anywhere near as distracting as it seems, though is a definite downside to the Micro-OLED optical engine compared to others.

The Micro-OLED optical engine only weighs 231 grams compared to the QLED at 355 grams, though at any rate, it’s not as compact or convenient as the Quest 3. That’s to be expected considering it’s using the same shell as the non-pancake optical engines.

For the QLED options, Pimax uses aspheric glass lenses. All three QLED versions use the same panel, with the 57 PPD model able to offer a higher PPD with different lenses to the others. The Ultrawide, on the other hand, is able to increase the FoV with the same lenses and screen as the 50 PPD model by essentially moving the screens further apart—reducing what’s known as stereo overlap.

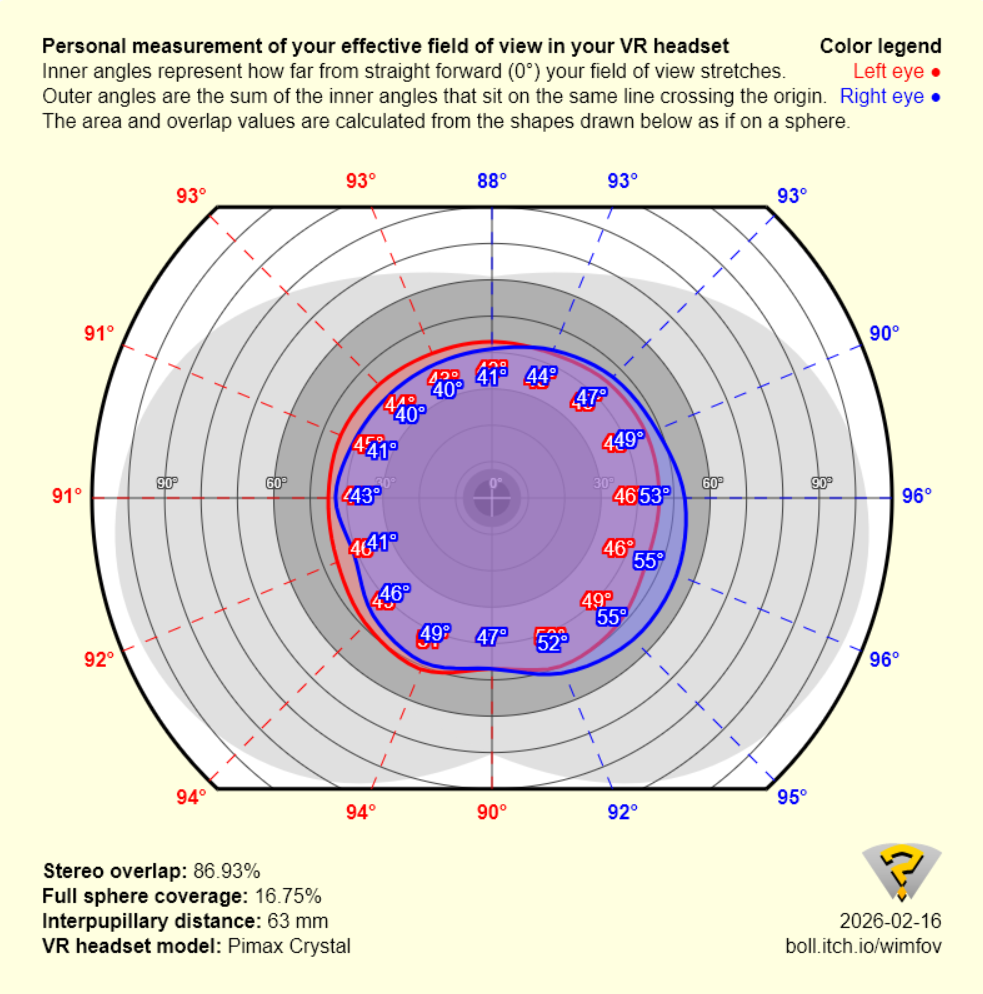

Stereo overlap is the area that is covered by both left- and right-side vision. It’s usually presented as a percentage, meaning the amount of L/R overlap; ie ~86% on the Micro-OLED Crystal Super. That’s a lot higher than the ~77% on the 50 PPD Crystal Super, and as someone that prefers more stereo overlap than less, mostly for keeping my vision clear and my head straight, the Micro-OLED once again comes out on top here.

Tests for FoV, such as Wimfov (seen above), can have varied results from person to person. As such, my testing should be at the very least consistent between the two headsets, if not necessarily the same as someone else’s.

You may be less prone to ocular mixups than me—perhaps I have a greater susceptibility to what is known as binocular rivalry, or in simpler terms, bad eyeballs—thus the 50 PPD QLED model may offer plenty of overlap. The Ultrawide model goes one step further again with less overlap. However, I prefer the increased stereo overlap of the Micro-OLED.

That’s true even though I play racing games in VR, which is one of the best use cases for a wide FoV. The added visibility comes in handy when you’re being overtaken by a late-braker or a serial shunter. Yet I don’t race enough to justify moving fully from Micro-OLED, which has a few other big benefits.

One being no screen door effect. You can chalk it up to a combination of all those aforementioned features, such as resolution, PPD, etc., but also the construction of Micro-OLED. Manufactured directly onto a silicon substrate, pixel density can be enormous on a tiny Micro-OLED display by comparison to larger OLED and LCD panels.

The Sony ECX344A, as is likely used here (BOE also makes a similar panel but Pimax names Sony here), has a pixel pitch (the distance between the centre of each pixel and the next) of 6.3 µm. A standard 27-inch 4K monitor is 165 µm. To put it another way, a 27-inch 4K monitor has a PPI of 163, whereas the 1.3-inch ECX344A has a PPI of 3,389. Even a much smaller LCD made for VR applications like BOE’s 5.46-inch 4K display has a PPI of 773.

A Micro-OLED is very small but densely packed. So much so that a human’s eyes aren’t very good at making out the gaps between subpixels on a Micro-OLED like they might a traditional monitor.

Look to the sky in Arizona Sunshine Remake while wearing the QLED Crystal Super and there’s obvious screen door effect. Compared to older generation headsets, and due to the high resolution offered by all Crystal Super models, this effect isn’t too bad, and less noticeable when you’re playing the game rather than looking for imperfections as I have been. However, with the Micro-OLED Crystal Super, and even when I’m intently interrogating the scene, I see no sign of the screen door. No traceable lines—nothing.

Look to the floor in the same game, or to the green guide that Pimax uses to warn you when you’re wandering out of your boundary, and you’ll spot some slight jittering on finer details on both QLED and Micro-OLED models. However, it is less noticeable on Micro OLED than QLED.

Then there’s vibrancy. Most know that an OLED panel naturally produces deep blacks, on account of the self-emissive nature of each pixel—essentially, per-pixel lighting. However, colours are also exceptional on an OLED panel and this Micro-OLED is no different. It’s noticeable in combination with white levels and contrast. Within bright areas, due to its comparably large lighting zones, the QLED optical engine washes out a good part of any colour. This is especially noticeable on the Arizona Sunshine Remake icon in SteamVR, which is completely blown out on the QLED compared to the Micro-OLED, and that tracks throughout the sunny game. Micro-OLED has no such washout.

Now to come crashing back down to Earth. I kept myself in the dark on the price tag for the Micro-OLED optical engine for the longest time, but I’m all too aware of it today. It will set you back $1,199/£920. The Pimax Crystal Super with the Micro-OLED is $2,199/£1,700, or with any QLED optical engine is $1,799/£1,393. So, the question is whether Micro-OLED is worth an extra $400/£307?

I have to say, yeah, it probably is. Though I’m assuming something about your character there. I’m assuming that you’re the type of person to spend big on a high-end VR headset to begin with. A budget-minded casual buyer might opt for the much more affordable Quest 3 and find that is plenty powerful, plenty fun, and plenty easy to use. The prospective customer of the Pimax Crystal Super 8K Micro-OLED is not that.

The Crystal Super is actually a pretty clunky device in ways. It’s not as convenient, nor as comfortable, and while it does have inside-out tracking, it’s still a tethered headset requiring a PC that’s able to handle a very high resolution. It feels like a VR headset that hasn’t got with the programme that even Valve, creator of the Valve Index, has ditched in favour of the streaming-first and standalone Steam Frame.

But the picture quality—oh, the picture quality—is too good on the Crystal Super to ignore. And the audio, too, from the optional DMAS earphones that keep the ear speaker dream alive—possibly the best thing about the Valve Index. As a headset for your average VR user, the Pimax doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. But for an enthusiast that talks a little too much about subpixels and screen doors, yeah, there’s a lot to like. Micro-OLED is seriously expensive but seriously good. At the very least, it’s a lot cheaper than the Apple Vision Pro.