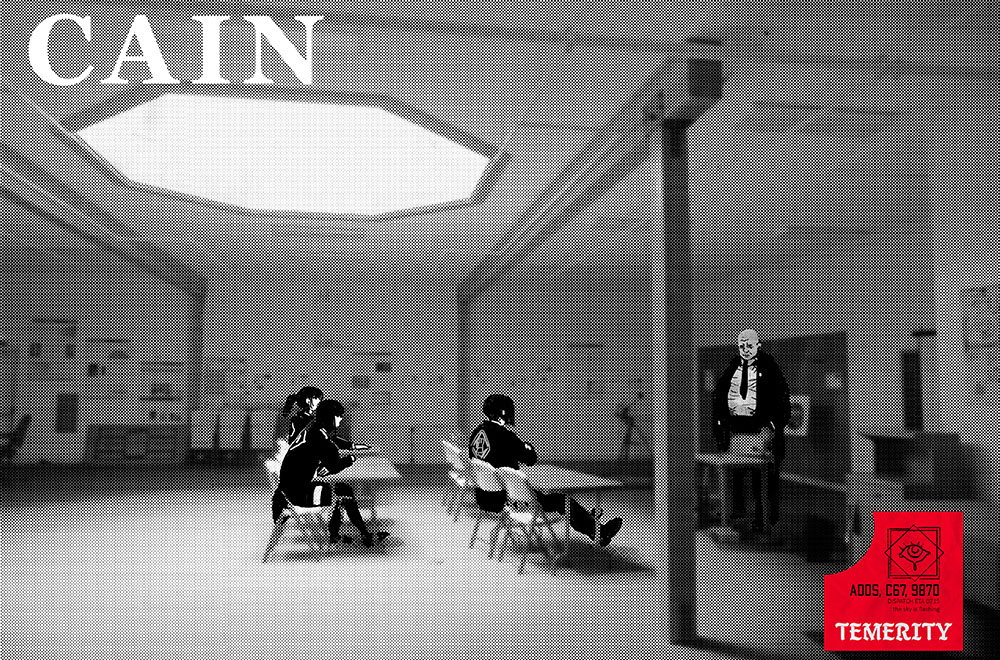

Games played entirely in the imagination are a tough sell. To successfully construct scenes, a player needs sturdy cultural touchstones, a strong visual identity, and a sense of what beats make a dramatic scene. Cain, the new tabletop role-playing game from the Tom Bloom (co-creator of Lancer and writer of webcomic Kill Six Billion Demons), offers as good of a hook as a person can get: It’s Chainsaw Man meets The X-Files, where players piece together clues left behind after a supernatural crisis event and exterminate the monster that caused it.

Cain casts players as exorcists — psychics recruited, trained, and employed by Cain, a supra-governmental force that manages psychic phenomena. The mission is simple: Enter the crisis zone and exterminate the sin, a monster manifested from human trauma.

“I’d compare the vibe very closely to [Neon Genesis] Evangelion,” Bloom told Polygon in a recent interview. “There’s this big, supernatural problem that’s totally outside of human control, and we have this massive, underworld-y organization that launches psychic supersoldiers at it. It’s a little SCP Foundation, a little XCOM.”

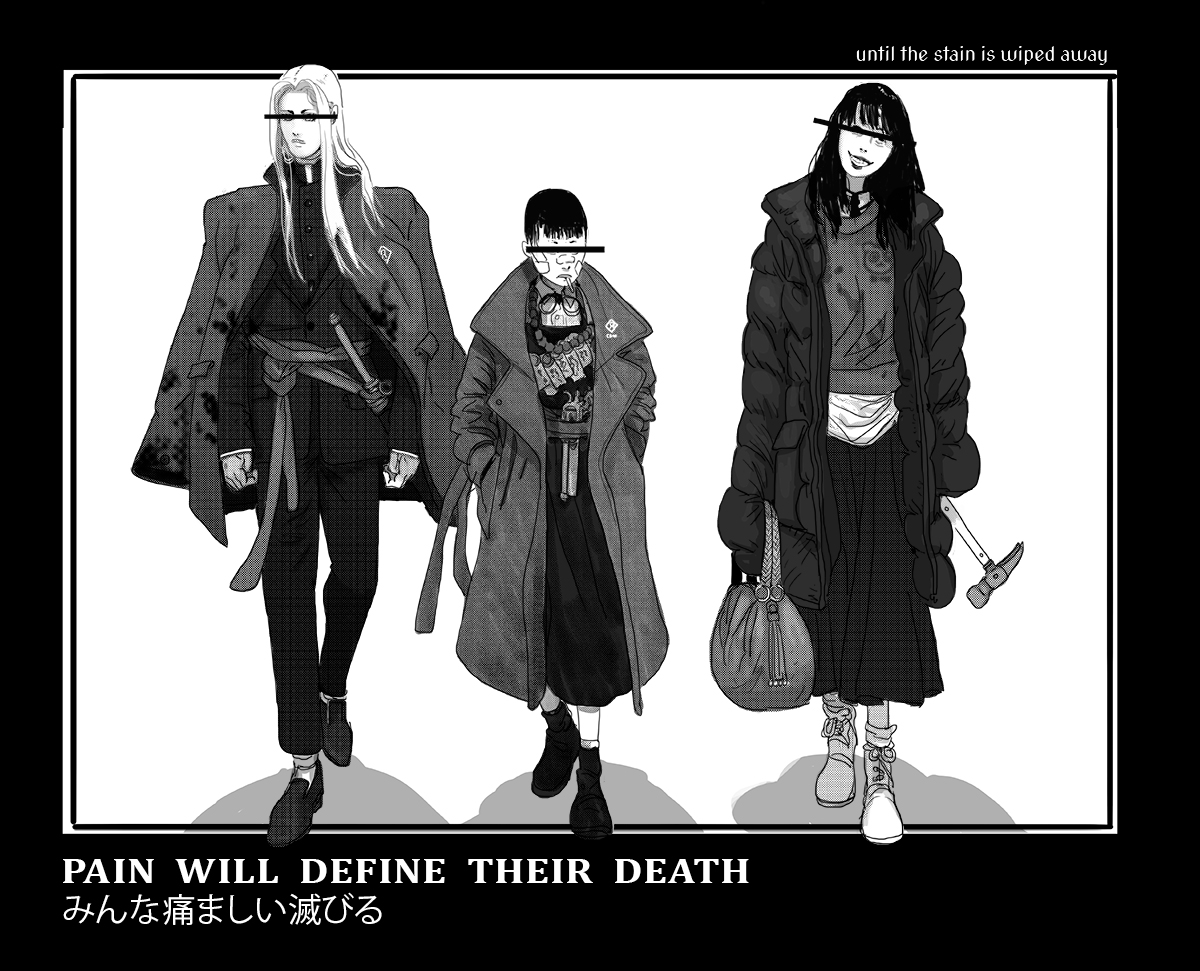

Just like its predecessors in the history of horror-tinged secret organizations (Chainsaw Man’s Public Safety, Evangelion’s NERV, SCP’s eponymous Foundation), Cain revels in the crushing horror of bureaucracy. Exorcists are “tools of Cain,” living on company land and paid in company scrip (a week of supervised absence costs 15 scrip; successfully executing a sin awards you five). Cain has one aim: to wipe out the stain of human sin, no matter the cost.

While Cain can seem like pure investigative horror, Bloom thinks about it more like supernatural shonen anime like Demon Slayer and Jujutsu Kaisen. “How those are all paced is that there’s an investigative period in which you learn what’s going on and you might have a few scuffles with the antagonist, and then in the climactic fight, you use those earlier experiences with what you’re fighting to get an advantage,” Bloom said. “I was trying to make sure that the investigative phase actually has weight in combat, and I’m pretty happy about that. I don’t think you can do it in a game where your primary opponents aren’t formed of human trauma.”

Cain’s missions play out just like the monster-of-the-week shows that inspired it. Exorcists enter a new location and are briefed on the broad strokes — what kind of sin they’re hunting, what initially caught Cain’s attention, et cetera. As their investigation continues, players may tangle with manifestations of the sin in combat, or face more mundane obstacles to their investigation, like law enforcement or paranormal documentary crews, before locating the sin’s dwelling and executing it.

Play is set out through scenes, described by the Admin (the formal name given to Cain’s game master), in which players state their actions and roll dice to determine the success of anything risky. The higher a character’s skill, the larger their pool of dice from which they draw successes. As the investigation drags on, the Admin imposes ramping consequences — killing non-player characters, sending low-level minions at the players — until the sin mutates into a catastrophic threat.

Cain’s dice system is key to maintaining this narrative tension. “Other games allow your character to improve over time,” Bloom said. “But the problem is that this pushes the odds of the dice in your favor so hard that it sucks the tension out of the game.” In Cain, no matter how much characters progress, rolls always carry risk in the form of a separate die rolled by the Admin to govern consequences. As a result, no hunt will ever be without complications.

As exorcists use their powers, they come closer and closer to manifesting an imago, their own version of a sin. Quite deliberately, it’s almost impossible to avoid accruing that trauma, so each outing draws the player numerically closer to becoming the very thing they’re employed to destroy. It’s another point of reference to series like Chainsaw Man and Blade.

“In a sense, you are what you’re hunting,” Bloom said. “You’re being used to fight fire with fire. There’s an inherent tension there.”

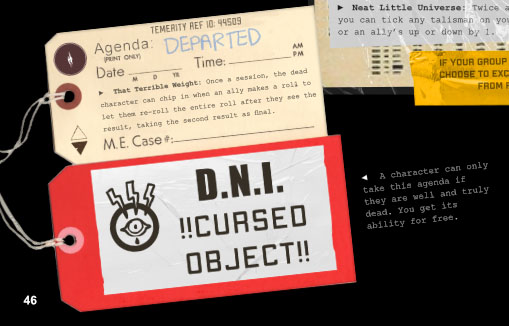

This struggle between individual empathy and bureaucratic heartlessness is a huge feature of Cain’s art. Bloom calls it “stickercore,” incorporating memos and ID cards into the book where a reader might expect standard text boxes, and creating a breach between the real world and the fiction.

“Why does manga get away with just being black and white?” Bloom said. “Well, it’s because they have screen tone, and screen tone adds texture. […] It had this certain aesthetic that’s manga-associated — manga has screen tone because they print on cheap paper.”

This manga inspiration extends to Cain’s characters, dressed in an eye-catching blend of streetwise fashion, combat gear, and mundane office wear. It’s a great microcosm of Cain’s stories, with stylish exorcists and horrifying Sins clashing against barren landscapes.

The end result is that with just a handful of photobashed illustrations and some creative typesetting, Cain has an unmatched visual identity. It’s a much-needed foundation upon which Cain builds its emotional core. The exorcists, gothic psychics drawn into a faceless organization beyond their control or understanding, don’t require any extra work to make compelling stories — they are compelling stories, waiting for players to inhabit them. Proud-worn inspirations, inspired visual choices, and a dice system that refuses to let up the pressure — all of this compounds into the amazing feeling that Cain is a game that actually has quite a lot to say.

“So much of what we do in society in general is just amelioration. It has nothing to do with curative justice,” Bloom said. “I wanted to make a game that was about that conversation. This person is suffering from this huge societal problem, but what are you going to do about the current situation? Are you going to follow your orders and execute, or are you going to spare this person and deal with the consequences of that? I think that’s an interesting question, and I hope that people playing this game will find that interesting, too.”

Cain is available now on Itch.io.