Imagine this: You tell your doctor that you're struggling with stress, and she sends you home with instructions to play videogames every week. Even better, your health insurance is going to cover a subscription to the game service, and maybe even a VR headset to play them on. That's the vision of Seattle-based company Deepwell DTx, and it's making real progress: the company's biofeedback software development kit for games just received FDA clearance for “over-the-counter treatments for the reduction of stress and as an adjunctive treatment for high blood pressure.”

Deepwell co-founder Ryan Douglas doesn't just think the news is good for patients (and medical device entrepreneurs), but also for gamers and game developers. Introducing games to the world's trillions of dollars in healthcare spending can “bring us back to the golden age of gaming,” he said on a call with me last week.

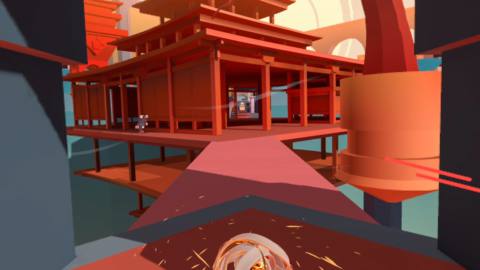

Deepwell has demonstrated its technology in VR game Zengence, which it calls a “mental health action shooter.” It sounds funny, since discussions about mental health and first-person shooters largely center on the claim that violent games disturb vulnerable young minds, but Douglas is convinced that not only are violent videogames not harmful (a recent Stanford study and others agree), they're valuable therapeutic tools. “It turned out that the action genre was one of the most therapeutic we had,” Douglas told me during an earlier conversation back in June.

Zengence isn't exactly Call of Duty, though: Its enemies are “wraiths” and you're shooting them with wizard beams, not hot lead. It uses the Meta Quest's microphone—this is the biofeedback component—to detect when the player is humming or chanting. When it picks up those meditative tones, which indicate that the player is exhaling, it sends an orb into the environment which reveals wraiths to zap with your mental health wand.

The basic idea is to get players into the relaxing, dopamine-rich “flow state” game designers and athletes often talk about, and to improve their everyday stress response by incorporating breathwork—a well-established stress management tool—into the mildly-demanding task of shooting accurately.

“It turns out, when we're heavily engaged in play, we learn at a highly accelerated rate,” said Douglas. “So we want to get people into environments where they're having a lot of fun, they're having a lot of flow, and that gives us the opportunity to do something called consolidation of memory, or to get you building new neural pathways. And as a result of that, you you can literally adopt new thoughts and ideas about yourself, but you can also adopt things more limbically, like something that would respond to your autonomic nervous system. You get a trigger, and you behave differently than you did before, because you have a new neurological pathway that's become preferred over time.”

Deepwell's next big regulatory ambition is to be granted Medicaid and Medicare codes that “provide monetary incentives for companies to develop, doctors to recommend, and patients to use” games that feature DeepWell's tech. While I digested the somewhat startling idea that doctors may soon receive financial incentives to recommend videogames to their patients, Douglas surprised me with left-field perspective: that it isn't just about changing healthcare, but about changing the videogame industry.

The way Douglas sees it, great games are already therapeutic, and developers don't necessarily have to design around Deepwell's biofeedback system to take advantage of the FDA clearance. For example, a hub of games meant for stress reduction, some of which make use of the breathing mechanic and some of which don't, would still qualify. They can also continue to sell their games outside of a healthcare context. The result, Douglas hopes, is that game developers will gain access to the healthcare economy while still making the kinds of games they want to make.

There are some conditions, though: No predatory monetization, and no unmoderated chat. “When you're highly dopaminergic, and there's a steady stream of hate speech coming into your ear and a whole bunch of social pressure, it could be a very radicalizing situation,” Douglas said. But for developers who aren't about loot boxes and open comms, Deepwell could be a new way to thrive.

The most effective mental health videogames are commercial games.

Deepwell DTx co-founder Ryan Douglas

“If you want to tell a great story, you have a fabulous game … now you can have that same format, except you're going to keep getting paid,” Douglas told me last week. “There's a whole economy coming here, tying back to these reimbursement codes. They're real. They're real dollars. They're very powerful. So with our clearance right now, we have access to about 70 million people through HSA. When that [Medicaid and Medicare clearance] kicks in, we talk about another 144 million folks, and exactly the people who need it: seniors, low income kids, low income families. And then it's a very natural progression. You tend to go: HSA cleared, Medicaid and Medicare cleared, and then the next step is very logically to the rest of the care continuum. So you end up with everybody with private insurance. So if you're a game dev, and you're just tired of building economies … this is going to be a real alternative.”

It'll be a symbiotic relationship. Douglas thinks that Deepwell needs good game designers on its side if this gambit will work, because wellness software with bolted-on “gamification” features isn't going to cut it.

“I think what happened in gamification is that the game designers were not really recognized for how much expertise they were bringing,” he said. “The most effective mental health videogames are commercial games. They were accidentally therapeutic. And the one thing they have in common is they were created by the masters. So it looks like the same skills that overlap into play, that are so important to get us heavily involved in a game—so much that we can't stop doing it—they have a ton of overlap with being therapeutic, too.”

Deepwell's FDA clearance currently allows the company's SDK to be used for products indicated for stress reduction and as a supplementary treatment for hypertension, alongside medication. The company is working on new biofeedback systems, and Douglas told me that “after more clinical work” he wants to target anxiety and depression, and said in a press release that Deepwell may also pursue treatments for pain, PTSD, epilepsy, sleep disorders, immune disorders, Parkinsons, and Alzheimer's.

Digital therapeutics are a relatively new industry that has grown significantly since the start of the pandemic. Daylight, for example, is a mobile app launched in 2022 that's used to help patients manage Generalized Anxiety Disorder. GameChange is an Oxford-developed virtual reality therapy aimed at agoraphobia. 20 digital therapeutics have been cleared by the FDA so far, according to Deepwell chief medical officer Dr Samuel Browd.

The new field faces skepticism over its effectiveness—can an app really replace a pill?—privacy concerns, and other criticisms. Douglas argues that good videogames are effective in part because it's medicine people will actually take; he told me that getting patients to comply with their doctor's advice, even when the ask is small and the side effects negligible, is a formidable challenge.

A lot of healthcare is already happening online post-pandemic: Therapists and psychiatrists are meeting with patients remotely, commercial videogames are already being used as therapy tools, and there are loads of “wellness” apps that haven't sought out validation from healthcare regulators and insurers. Anecdotally, VR games have been effective fitness tools for people I know.

The voice control mechanism in Zengence doesn't seem especially challenging for other game developers to replicate, but Deepwell and other digital therapeutics companies bring clinical research and knowledge of the healthcare industry, insurers, and regulators to the table that game developers don't have. I'm not so sure that Douglas' golden age of gaming is really imminent—a more conservative outlook is that there'll be a new crop of interesting mobile and VR rhythm games that can now tap into healthcare revenue streams—but the idea that integrating videogames with the healthcare economy could emphasize their best qualities is certainly intriguing.