Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist '80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

I've been spoiled. The modern RPGs I spend my time with are filled with waypoints, automaps, and quest markers, all designed to keep me on task and pushing forward. The old ones I choose to play today are rarely more than a decent emulator away from having instant-access save states and handy turbo features on tap, able to compress all that grinding and walking around into easily digested chunks.

And why shouldn't I use these features if they're available? Why spend hours walking in circles when typing “[Game Name] maps” into a search engine can show me where I need to go in an instant? Why jot down my own notes when the internet's filled with FAQs and videos?

Because I've taken it too far.

The intent of these modern tools is to be helpful, flexible, convenient. But all too often the reality is I end up thoughtlessly sanding games down into smooth, efficient, samey experiences. I don't invest myself as fully as these games deserve. And when that happens, I miss out on the chance to make an adventure of my own, to take my route through a game and come away from a game with a personal story to tell instead of a tidy checklist of completed tasks, the same as everyone else's.

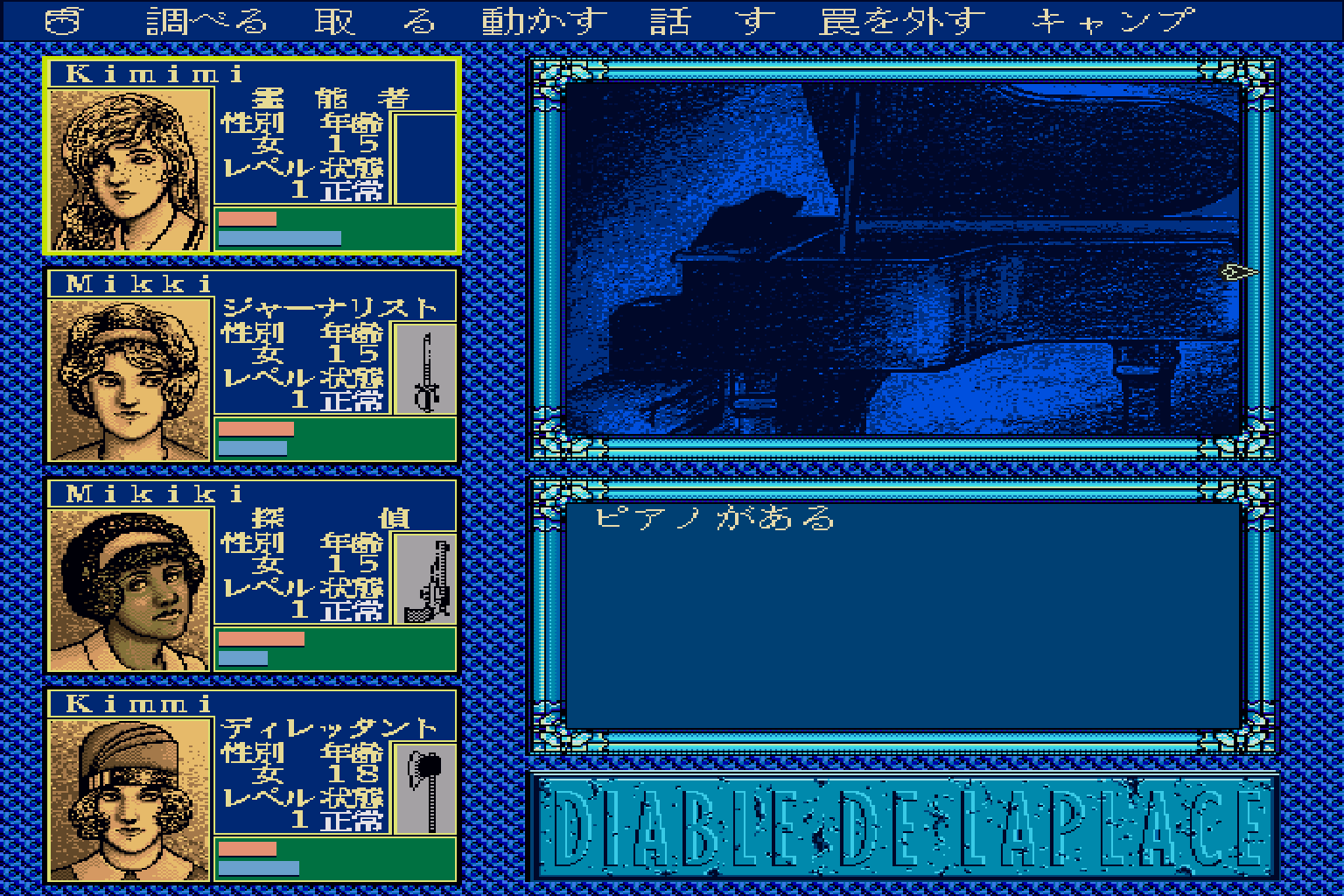

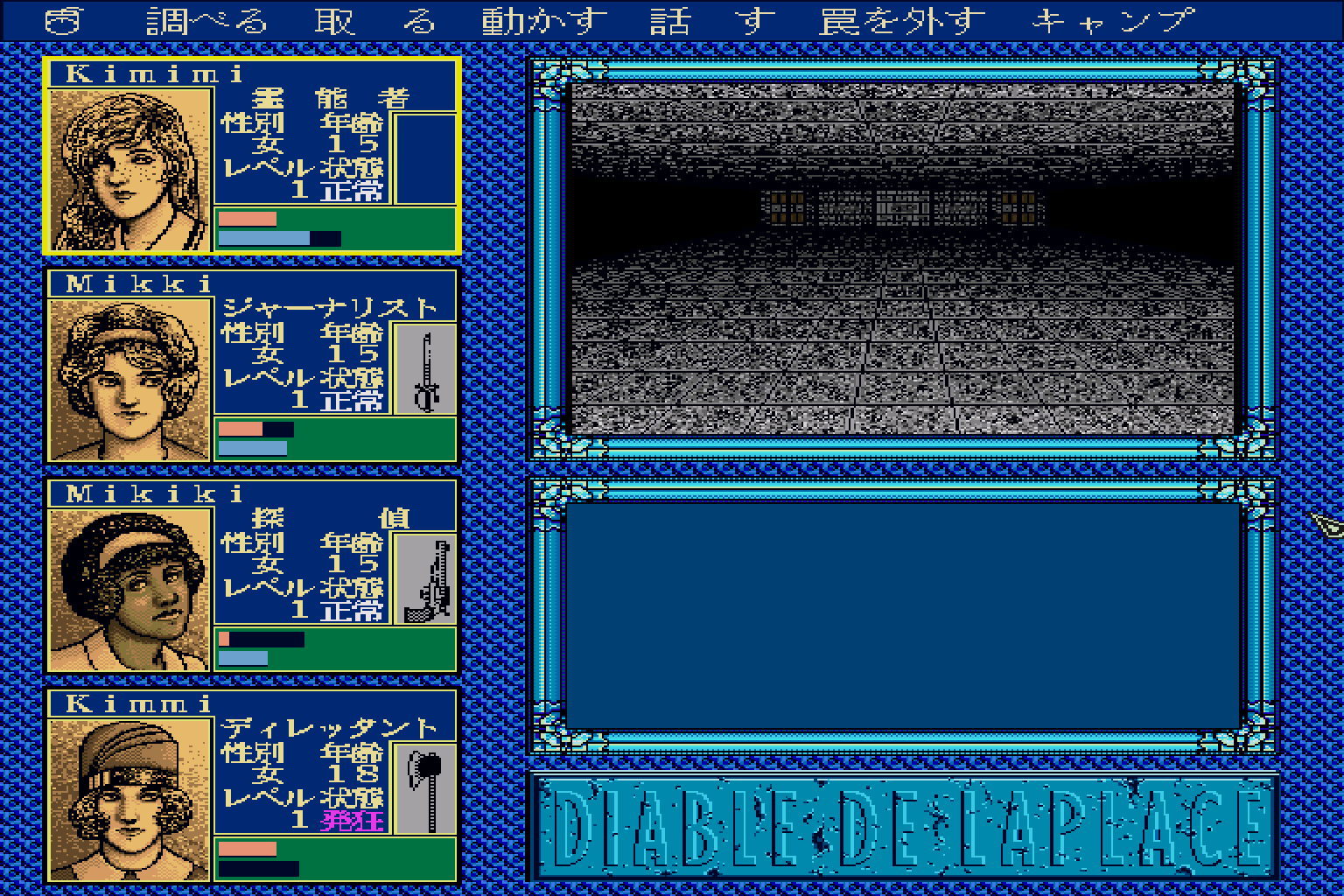

So I'm going to fix that—for one game, at least. I'm going to play Laplace no Ma, a brilliantly unsettling 1920s-themed dungeon crawler that lets me send a team of detectives, psychic mediums, and journalists into a spooky mansion, the old fashioned way. The really old fashioned way. I've printed out copies of the game's official graph paper, I've got the pointiest pencil in the house to unleash upon it, and I'm ready to go.

Venturing forth

The rewards for the daunting amount of effort I'm about to put into this game turn up much faster than I expected.

The first map sheet, included in the box as standard back in the '80s/'90s and now bundled with the digital re-release as a convenient PDF, isn't blank, but comes with a few notes and a small segment of the mansion's first floor filled in, and I'm enthralled by this place before I've even finished creating my party. Why is that fireplace important enough to mark down? What can I do there?

And what about the unfinished corridor leading deeper into the mansion behind the stairs, where does that go? Is it spooky? (Surely it's going to be spooky).

By encouraging me to look and think like this the pace of the whole game instantly slows down, and this unhurried mood changes my relationship with everything. If I'm hand drawing individual map tiles on paper, then taking a few minutes to check up on something I was curious about in the manual, or spending a good chunk of time taking my freshly made party around town to stock up on supplies and weapons is hardly disrupting the flow of the game, is it? I'm giving my imagination the room to breathe, and my mind the time to pay attention—really pay attention, not just check a guide every now and then to make sure I'm still on the right track.

Because of that I noticed how precisely my first view inside the mansion matched up perfectly with the map. The stairs were right where I expected them to be, and I started off next to the door leading to the room with the fireplace, just as expected.

It sounds like an odd thing to say about a game that runs in a tiny window of an already (by today's standards) low resolution screen, but staring down a corridor I noticed how detailed everything was, and how far into the distance my view stretched. I could see everything from the ground at my feet to the double doors right at the other end of the hallway, as well as every set of doors down the sides along the way. When being able to accurately map where I am and what I'm looking at could mean the difference between life and death, these things matter.

Although “accurate” is kind of open to interpretation when it comes to my wobbly lines. The scrappy notes I've been making down one side of the first floor's sheet now overlap a room's western edge, and there's a ghostly outline of a mistake lingering around on the opposite side of the paper. I did think it was strange that two rooms right next to each other had the exact same layout, not realising that between swigs of coffee I'd turned myself around and accidentally wandered into the same place twice.

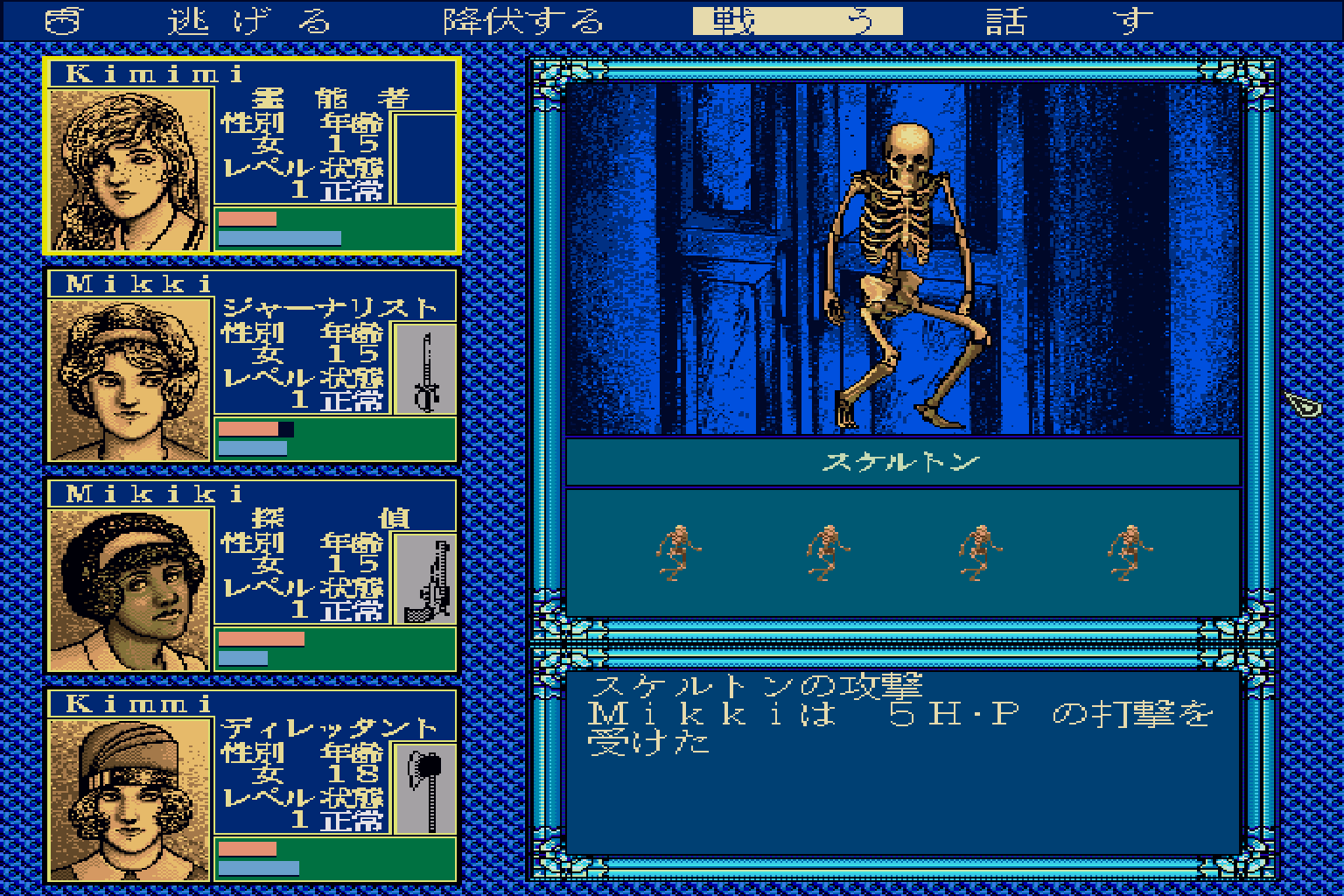

To make matters worse, running away from many potentially life-ending random battles literally moves my team several tiles away and facing a different direction. It makes sense, in theory—if I was running away from flesh eating monsters I wouldn't pay too much attention to where I was going or how I got there either. But as there's always a real chance I'll end up completely lost in a different room and facing a blank wall it almost makes dying to a small army of zombies and being forced to start over feel like the superior choice.

I could give in. Find a map online. Nobody would bat an eye at someone FAQing their way through an old dungeon crawler. So why make things more difficult for myself? If Digital Eclipse's Wizardry remake can include an automap and still receive hundreds of positive reviews, who am I to argue? It's not 1990 anymore and I don't have to pretend it is.

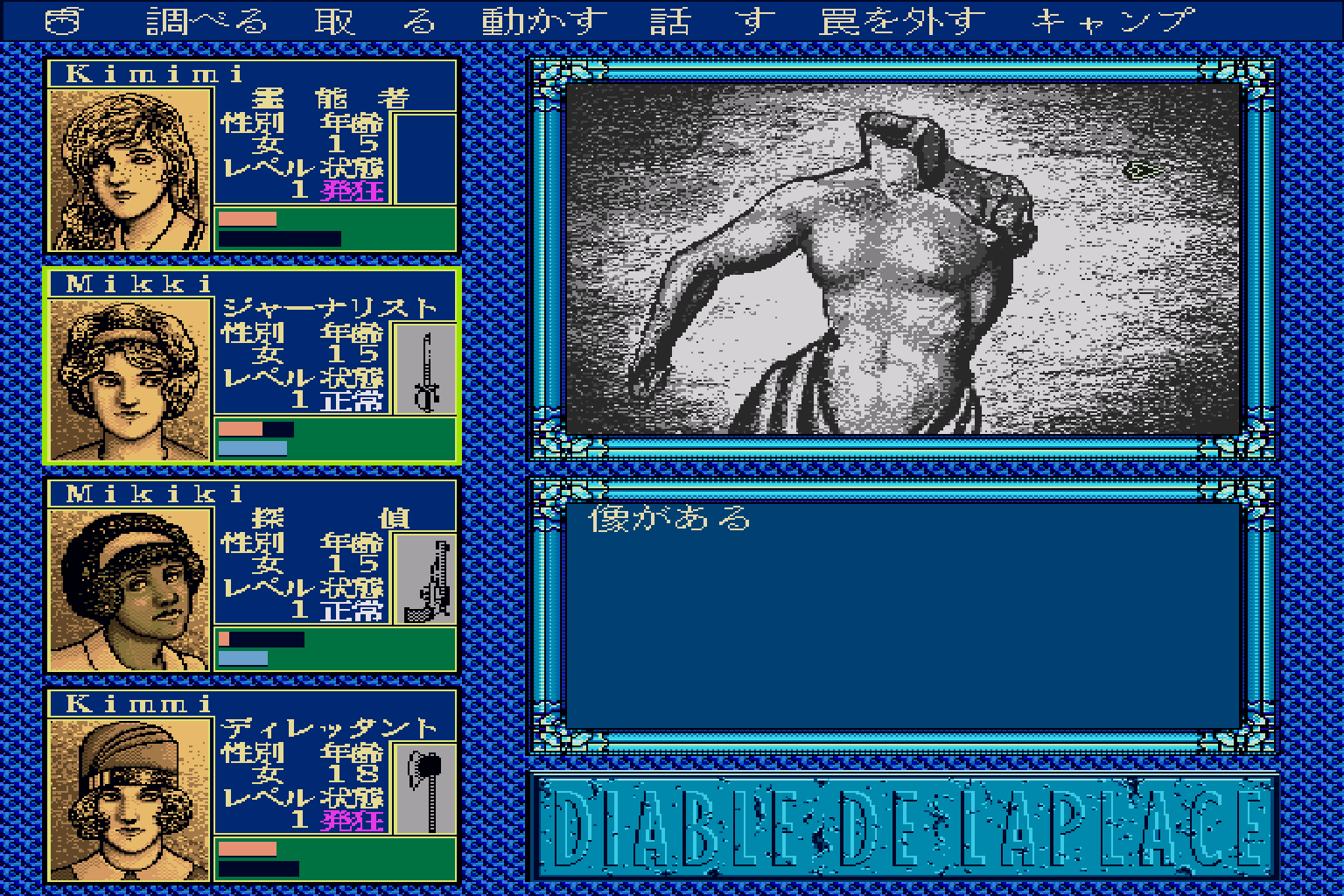

I let the question stew for a bit as I direct my team, one of them driven mad through MP loss, to continue poking around in the dark. I'm making things more difficult for myself because I'm enjoying it. It's fun, like… like getting smacked around and kicked off a cliff in Elden Ring is fun. I want to shout and swear and chew straight through this damned pencil, but I know I'm coming back for more. Because this isn't Humming Bird Soft's game now, it's mine. My team. My experiences—good, bad, and plain embarrassing.

Dear diary

I love this imperfect mess I've made. I'm drawing over my own notes. Marking secrets. Scribbling little half-formed thoughts down as odd bits of dialogue come my way. Writing ENFORCED GHOUL ENCOUNTER in the margins and then underlining it because I don't want to get caught out next time.

Just below that is another helpful note for future me: KEY INSIDE, a happy memory of finding something useful, safely stored forever on paper. Not even Etrian Odyssey's mapmaking features can match how personal it is to create something like this, the sequential numbers I've used to mark various points of interest forming a sort of diary of my path through the game as I go.

By modern standards I have spent a very long time achieving very little. The amount of ground covered since I started playing has been painfully small—I've investigated about a dozen rooms, found a few unusual spots to keep in mind, a small handful of items, and died more often than I'm prepared to admit—and I know that if I'd been given a quest list, a decent HUD, and an automap I could have covered the same ground in minutes, rather than hours.

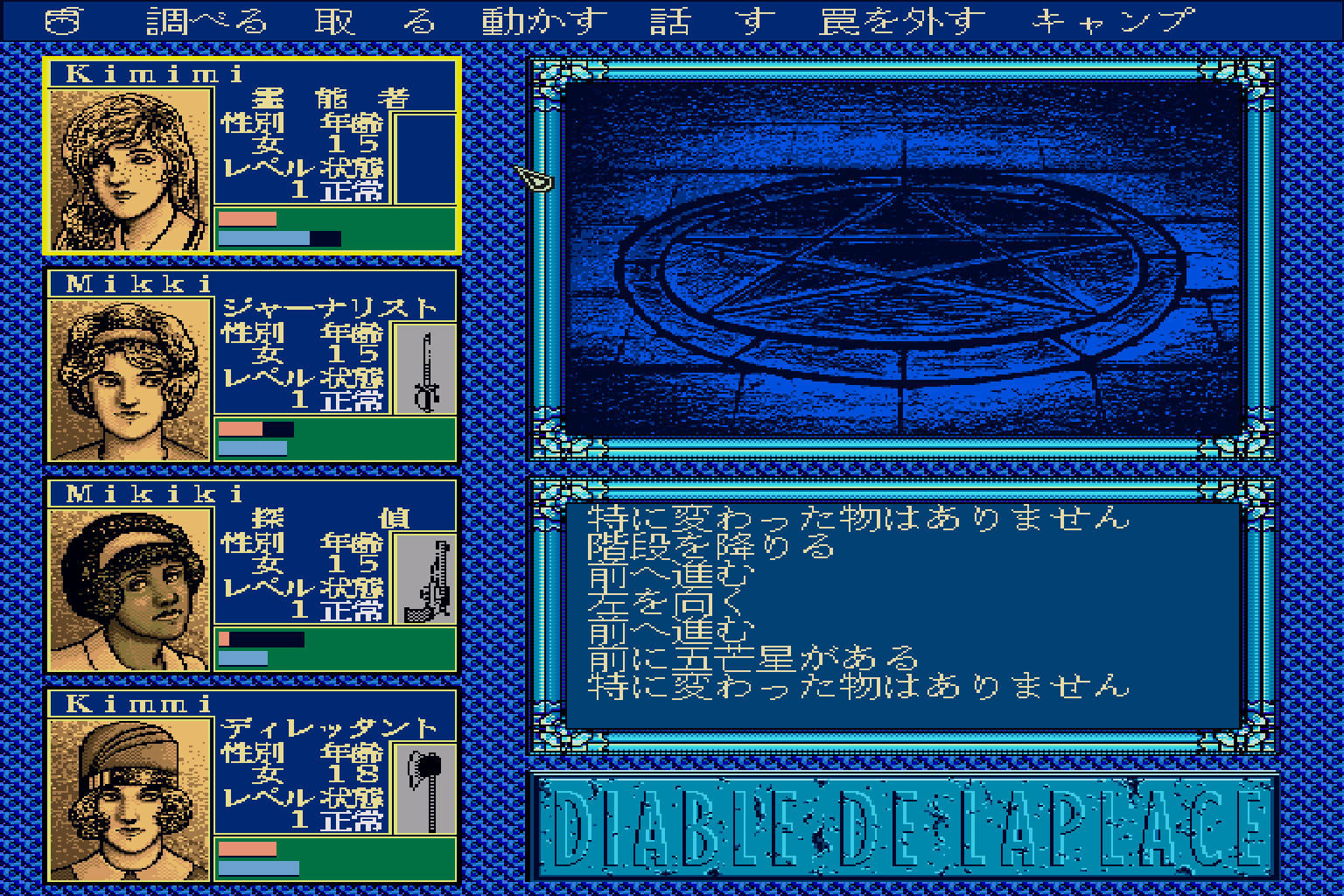

But by Laplace no Ma's standards I've risen to the challenge, and lived(ish) to tell the tale. The game doesn't care that it's old, and it definitely doesn't care that modern release schedules demand a punishing combination of utter devotion and blistering clear times just to keep up with the next big thing's season pass. My next goal here isn't supposed to be to perform “Take Key B from 1F X12 Y7 and use it at locked door 6 [see map]” in the most efficient manner possible, it's to take some tentative steps into the basement. It's to cautiously investigate the teleporting pentagram I found in a hidden room behind a bookcase, if I dare. Maybe even to safely make it back to town and restock on precious supplies.

I don't need to be so hard on myself. I don't need to make tangible progress, just to explore. I need to doodle little cartoon skulls in the margins of my maps. I need to spend more time having fun than counting down the hours until I can move onto the next game.

I need to take this attitude into the next game I boot up, no matter how new or old it is. I'm tired of winning—I just want to play.