There’s always a city. There’s always a lighthouse. There’s always a man. There’s also always an opportunity for a company to create a new game in a franchise to make some money, and while I recognize that’s exactly why a fourth BioShock game is in development, it’s hard to stop myself from growing more and more excited about what it might be.

BioShock Infinite, the last in the series, was released in 2013, and at the earliest, the next one, now in development at 2K’s new Cloud Chamber studio, hits next year. That’s a massive nine-year gap, which has hopefully given those at Cloud Chamber enough time to stir on what a new BioShock game needs and doesn’t need – it has for me, at least.

Ignoring rumors of above-ground and underground cities and Antarctic metropolises – because after all, those are just rumors until Cloud Chamber reveals what it’s cooking up – here are five things the next BioShock needs to do and three things it does not.

Needs: A City

If there’s one thing people think of when they think of the BioShock franchise, it’s the cities that players inhabit. Be it the first two games’ underwater utopia-turned-dystopia Rapture or the high-in-the-sky Christian religion-inspired Columbia of Infinite, the city itself was a character. Rapture was iconic as an underwater city, filled to the brim with 1960s glitz and glamor. It was also designed in such a way that finding your way around was easy.

Columbia was a bit more open, leaning heavier into the shooting gallery aspect of the FPS genre, but it was saturated with color and iconography that made a seemingly bright and sunny place feel daunting and alien. If one thing is certain, Cloud Chamber’s BioShock must feature a setting that’s long-remembered after its debut.

Needs: A Strong Narrative That Highlights The Flaws Of A Particular Philosophy

At its core, the first BioShock about the flaws in objectivism, particularly as it’s presented in Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged novel. It’s not trying to hide that, either (see: that character named Atlas). John Galt’s utopia is Rapture, except gone wrong. What was supposed to be a perfect paradise for artists, doctors, engineers, and entrepreneurs who wanted to break away from the Church and the governments above the surface was quickly destroyed by class warfare after the discovery of ADAM. It turns out the ultra-rich are always going to do what the ultra-rich do regardless of where they’re living, huh?

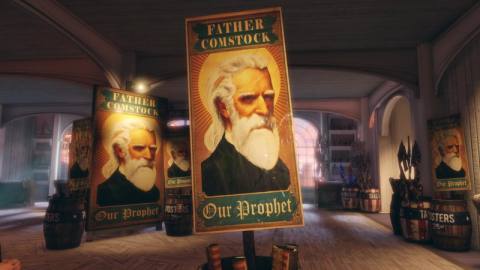

On that same note, Columbia also represents an ideology perceived as a utopia that quickly becomes anything but when put into practical play. A society built on the foundation of God, led by one man who thinks the rest of the world should fall in line behind America – what could go wrong? Well, if said “one man” begins to think he is God, or at least someone who thinks God looks like him and acts like him, a floating and isolated city quickly becomes a place rife with oppression, particularly for people of color.

At the heart of both BioShock, BioShock 2 (which largely continues the objectivism critique of the first), and Infinite are stories that critique these philosophies in unique sci-fi ways. It’s the commentary on real-world philosophy that’s core to the pillars of the series’ storytelling, and without that foundation, the next could risk becoming blasé, losing what makes these games interesting in the first place.

Needs: Plasmids And Vigors

Memorable settings and characters aside, BioShock is also a fun and tense first-person immersive sim – though Infinite leans further into being a straight-shot shooter. What makes the series’ combat so great isn’t the guns – in fact, I’d argue the guns need some heavy tweaking to stack up against other immersive sims like Deathloop – but rather, the plasmids and vigors.

These are essentially magical abilities that come by way of ingesting something you probably shouldn’t. It can be the ability to shoot fire, ice, lightning, or even a flock of crows. Instead of shooting an enemy, you can look for oil on the ground to light them up with ease. Perhaps they’re standing in water – a quick shock of electricity would take them out much faster than your measly pistol. These almost puzzle-like scenarios that BioShock has traditionally built into its combat are what make it memorable at all.

Needs: A Mascot Enemy

When you think of enemies in these games, you probably think of the Big Daddy. The same can be said for the Songbird of Infinite. They’re the stalking brutes of each entry, and anytime they appeared, you knew bad (for you) things were about to go down. They’re meant to up the ante of combat against standard mobs while injecting some terror into the formula. Everyone remembers their first encounter with a Big Daddy or the screech of the Songbird as it crash-lands onto the roof of the building you’re in.

These enemies are the mascots of their respective games – they reside on the covers, too – and the next BioShock needs one that stacks up against them. Shooting mobs is fun, but a mascot that terrorizes the setting with the ability to appear at basically any time is what keeps us on our toes.

Needs: An Omnipresent Antagonist

Both Andrew Ryan and Zachary Hale Comstock are seldom seen but often heard in their respective games. They almost mock you as you navigate Rapture and Columbia, discouraging you from further destroying what they’ve supposedly built. As discussed above, Andrew Ryan is the Ayn Rand representation of Rapture’s objectivist society.

While Zachary Hale Comstock is reminiscent, if a bit on the nose, of Anthony Comstock, a 19th Century self-proclaimed anti-vice man who attempted to censor and remove anything not upheld in the Bible. Much like his real-life inspiration, Zachary wanted God present in every aspect of life, but Zachary was able to literally rise above (into the clouds) to build the city of his godly dreams.

Andrew Ryan and Zachary Hale Comstock were both easy figures to want to take down, largely due to their always-in-your-ear pest-like nature. They mock you, preach to you, and ultimately oppose you every step of the way (when they aren’t controlling your mind, of course) until you get to finally take them down. Both men go down with ease, too. Funny. Anyway, their presence in their respective games is the icing on the cake that is the narrative of BioShock games, and nobody wants a cake without icing.

Doesn’t Need: An Open-World Design

There’s a non-zero chance the next BioShock is an open-world game. If that happens, there’s a non-zero chance that Cloud Chamber makes a really interesting open-world game, proving this entry completely wrong. A new game in the series does not need to be 40 hours long. One could argue that existing in these settings would be exhausting after 15 hours, and if it’s open-world, it more than likely would exceed that.

Plus, open-world design often introduces side quests, an abundance of collectibles that many don’t really care about, and a lack of unique polish. That’s not to say open-world games aren’t polished – in fact, many are, but BioShock levels have always felt more personally designed with a developer’s vision in mind. In an open-world take, Park B might be closer to a copy-and-paste of Park A rather than one park designed to house bees to help pollinate flowers with another designed to be a celebration of art and culture (looking at you, Silverwing Apiary and Dionysus Park). Again, Cloud Chamber might create an open-world that’s better than both Rapture and Columbia, but I personally don’t believe the next BioShock needs an open world.

Doesn’t Need: A Live-Service Play Model

Though I can accept an open-world BioShock, I’m absolutely opposed to it resembling anything live-service. If the franchise has done one thing right, it is committing to single-player, narrative-driven experiences, and it should stay that way. Playing with friends and strangers while attempting to pop some colorful loot out of an enemy is fun, but the inherent design of live-service games would remove the tension and thrills of a BioShock game.

Imagine killing your first Big Daddy and seeing two purple orbs, a blue orb, and one green orb pop out of its helmet? Imagine unlocking a Songbird outfit after the Songbird goes down in Infinite? Do both scenarios sound cool on their own, right? Sure. But when placed inside a game that has presented its narrative tension as the priority, emphasizing something like loot or being able to emote to another player feels odd.

Doesn’t Need: A Direct Connection To The Games Before It

BioShock and its sequel were connected. Infinite was not directly connected to its predecessors, although the use of multiverse theory did allow the game to harken back to Rapture. However, Infinite’s Burial At Sea DLC directly connected the games, making the events of BioShock only possible because of some things and characters in Infinite. That’s fine – it’s not surprising that Infinite director Ken Levine wanted to connect that title to the first game in the series.

However, that story is a closed-loop now thanks to the events of Burial At Sea. There’s no need for Cloud Chamber to associate its game with its predecessors. 2K has named Cloud Chamber the new BioShock studio going forward, and this team’s first entry in the franchise should represent that. It should say, “we’re the new BioShock team, this is our first crack at the series, and this is what BioShock is going to be moving forward.”

What do you think the next BioShock game needs? Let us know in the comments below!