The Game Awards is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. But for a full decade before The Game Awards, there was another, rowdier game-honoring awards show produced by Geoff Keighley: the Spike TV Video Game Awards. Just like the modern-day Game Awards, Spike’s show aired live, but it was on an actual television channel, without a Twitch chat to accompany it. It had skits. It had a celebrity host; in 2004, that was Snoop Dogg. And today it is a high-octane time capsule into how video games were classically marketed side-by-side with extreme sports, Mountain Dew, and lingerie-clad models.

There’s an incomplete, heavily edited version of the 2004 Spike TV Game Awards on YouTube; sadly, the full version appears to have been lost to time, despite my searching. But in an effort to understand what was gained — or lost? — when the “Oscars of gaming” fully transitioned into an independent operation divorced from Spike TV, the self-proclaimed “First Network for Men,” I decided to rewatch as much as I could. For science.

The first half of the YouTube video I found, uploaded by a user named PAPAGEORGIO84, includes a different Spike TV segment called “The Ultimate Gamer” in which one lucky guy wins a home makeover for his gaming setup. It’s a similar time-capsule trip but it actually ends up being extremely boring to watch so I skipped most of it.

The actual awards show starts off with Snoop Dogg doing a skit. Here’s a big thought: Some of the vibes of this old show could stand to return. I for one would love to see Snoop hosting TGAs this year (or really any year). I don’t know that the “Cyber Vixen of the Year” award should get a reprise this year (or, again, any other year… ever), but TGAs could use a host like this.

In the cold open, Snoop’s playing golf, complete with an argyle sweater vest, on one of those miniature home office golf sets. This is to set up Peak 2004 Famous Athlete Tiger Woods walking out of a nearby trailer wearing a fur coat, gold necklaces, and a fedora over a black toque. They both look adorable in their respective “switched” outfits. Tiger Woods then wonders aloud if PGA Tour stands for “Pimp Golf Association.” Then he points at the camera and tells us to game on.

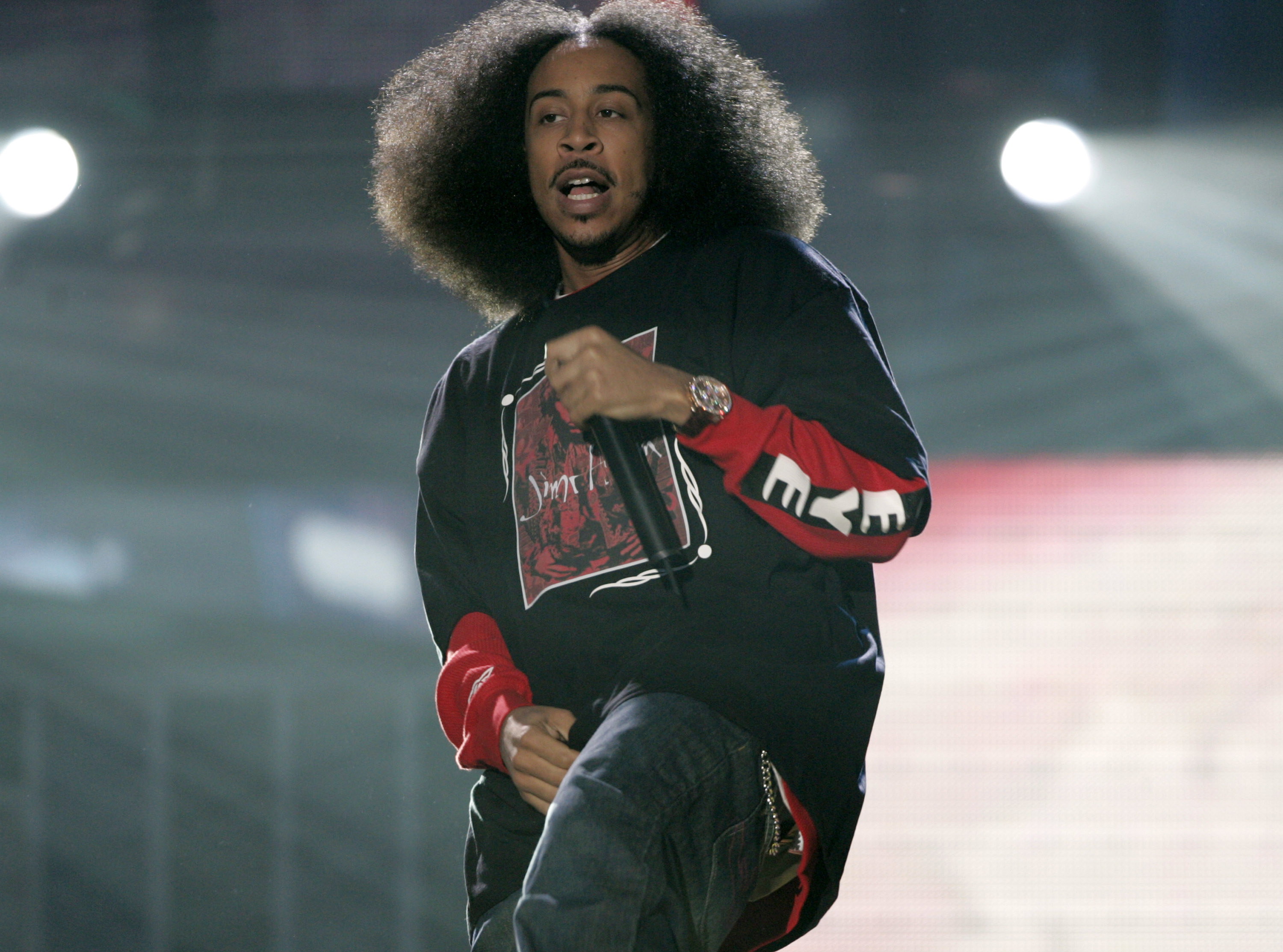

In the theater, attendees are treated to a CGI version of the rapper Ludacris greeting the Video Game Awards crowd. Luda is surrounded by other CGI dudes, whom he starts beating up. (This is probably a promo for a Def Jam game; he was in several of these in this time period.) Then, of course, we get IRL Ludacris out on stage, performing “Get Back.” There’s a live drummer, bassist, and guitarist accompanying this; Wikipedia tells me this is a rock remix of the song featuring Lazyeye. Rap-rock was huge during this time (although it usually didn’t feature people who could rap well). The performers do not play a shortened version of the song. They fully complete the track. The audience applauds, and then it’s time for… somehow, another musical performance? The early-2000s hip-hop energy and undiluted joy in this show is honestly exhilarating compared to the formality of current TGAs.

In a voiceover, Snoop rattles off a list of guests who will be appearing, ranging from Lil Wayne to John Madden to Michelle Rodriguez. With equal speed, he then lists off more musical guests who’ll be showing up — Busta Rhymes, Mötley Crüe, Sum41, and on and on.

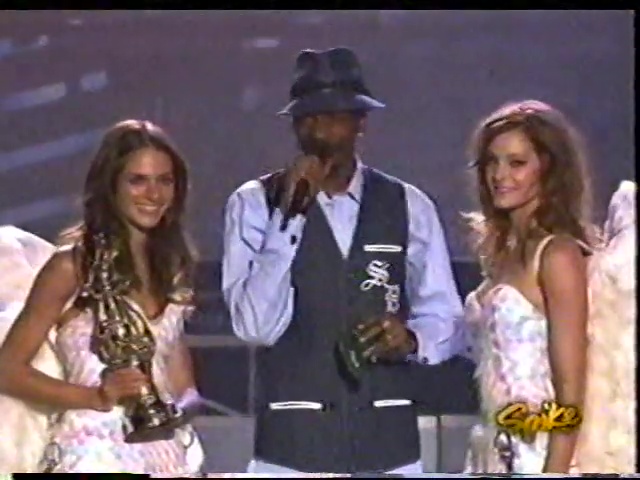

Before Snoop Dogg actually comes out on stage, radio maven Funkmaster Flex appears behind a turntable setup, serving as his hype man, introducing him as “the biggest rap star of all time.” Snoop Dogg enters wearing a vest over a button-up shirt with jeans and a fedora. “Video games are blowing up so crazy right now,” Snoop says into his handheld mic, “You know what I’m saying? Spike TV wanted me to have a co-host. At first I was like, hell nah. But then I realized who they had in mind.”

Snoop Dogg then introduces… himself. Again. But now he’s CGI and on a secondary screen. The CGI Snoop tells us, “Real people are played out, fool.” Snoop points out that there’s one thing real people can do and he uses a remote to turn off the CGI Snoop.

Snoop then introduces an award that is amazingly called “Best Performance By a Human Female.” There is an accompanying “Human Male” award as well. In the previous year, 2003, this award was just “Best award for a Human” — 2004 is the first time it got divided up by gender. (2003 was also the first-ever version of this awards show, by the way.)

“If there’s one thing I love, it’s human females performing for me,” Snoop says. “Which — ladies?” He gestures to the ceiling, from whence two Victoria’s Secret angels descend on wires. Snoop thrusts the mic into the face of one of the two women, who mechanically intones a line about the awards themselves, which are: “The Vector Monkey — awesome, isn’t it? It makes all those other award show trophies look like junk.”

This is around where I’m remembering why I and so many other people did not like this awards show at the time; it’s not all fun musical performances, sadly. There is lots of talk of how bad the Vector Monkey statue looks.

As I half-watch the clips of the nominees for Best Performance By a Human Female, Idiscover that there’s actually a separate Voice Actor category, and that the Best Human Female category appears to refer only to characters who were modeled after specific human beings (albeit not necessarily with mocap tech). For example, one of the nominees is Jennifer Garner for her performance as Sydney Bristow in a 2004 Alias video game. The Vector Monkey goes to Brooke Burke for her performance as a character named Rachel in Need for Speed: Underground 2.

Who the hell is voting on these awards? Here’s the answer (according to a Spike TV press release reposted on thefutoncritic.com): “Winners for the Spike TV Video Game Awards were determined by votes from Spike TV’s Advisory Board, made up of a group of gaming industry experts, and consumer voting […] More than 4.6 million gamers and Spike TV viewers logged on to cast their votes for their favorite games.”

Pulsing techno music plays as Brooke Burke takes the stage, delivers a two-sentence acceptance speech, then books it. I will learn, as the show goes on, that this short “speech” length is standard across all winners and categories. Immediately afterward, Funkmaster Flex yells into his mic, “And now, hot girls read cheat codes!”

We get treated to a clip of a woman wearing only underwear reciting part of a cheat code in a sultry voice. The audience is mostly silent during this part until a couple of people titter awkwardly. It’s grim.

Next up, BMX rider Mat Hoffman walks out with pro skateboarder Bam Margera. Did you know that there was a Mat Hoffman’s Pro BMX game in 2001 and a sequel in 2002? Margera, meanwhile, made regular appearances in Tony Hawk games. The pair read some jokes off the teleprompter about fake, hyperbolic injuries they’ve incurred in their respective sports, then Hoffman tells us it’s time to announce the winner for Most Addictive Game, “fueled by Dew.” This was a fan-only vote, Margera reminds us, before name-dropping Virgin Wireless Mobile (because, uh, you have to use the internet to vote? Sure).

The most addictive games included City of Heroes, which gave me a nice nostalgia surge, Donkey Konga (of all things), The Sims 2, Katamari Damacy, and Burnout 3: Takedown. They don’t announce a winner, and at this point I realize that the voting is going to happen live during the show itself. There are no Twitch drops during this show because we still have seven years until the livestream service is invented.

Funkmaster Flex then introduces “the next generation of sports superstars,” Bobby Crosby (who had appeared in MLB 2005) and Freddy Adu (who was in FIFA 2005). Their staged bit is that Bobby is too busy playing games on his PSP to read his part on the teleprompter. Apparently, the PSP had only just come out in Japan, and “this one’s the only one in the country.” Freddy makes a joke about selling it on eBay and runs offstage with it. Bobby takes over reading the nominees for Best First-Person Action, including some absolute all-timers like Half-Life 2, which actually loses out to Halo 2 (Half-Life 2 does win other awards later in the show). There’s also Unreal Tournament 2004, Far Cry, and Doom 3 in this category — a truly stacked year for FPS games.

Michelle Rodriguez and Ron Perlman are there to accept Halo 2’s award, which feels like a surprising amount of star power even by today’s standards. Also present: Bungie composer Marty O’Donnell (because… sure?). Ron Perlman fires off a one-sentence acceptance speech in which he gestures to his character on the splash screen and says it’s “the best I’ve ever looked.”

Next is time for Tony Hawk, who is not in attendance to talk about a Tony Hawk game, but rather to hype up Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, which is one of the games in contention for the big GOTY prize at the end of the night. Each of these nominees will apparently get a little hype cycle throughout the show.

Hey, and now it’s time for, as Geoff Keighley would say, a “world premiere” exclusive. Snoop returns to introduce a trailer for The Godfather video game adaptation. In looking up how this game did, I learned that James Caan lost out on the 2006 Spike TV Best Supporting Male Performance award to James Gandolfini who appeared in The Sopranos: Road to Respect. The early 2000s were all about gangster prestige game adaptations. In any case, the 2004 trailer is mostly just a cutscene featuring James Caan in CGI form. The tagline? “An offer you can’t refuse.”

“That game looks mad crazy,” says Funkmaster Flex, before introducing boxer Roy Jones Jr. to talk about some nominees for best driving game. Once again I am baffled that the career of the person introducing the award has absolutely nothing to do with the nominee(s) they’re talking about, but that’s probably due to the types of content that aired on Spike TV (extreme sports) and not really about the video games of the era. These were the gettable celebs!

Anyway, Best Driving Game is sponsored by the Pontiac GTO. After the clip reel of nominees, an actual Pontiac GTO rolls up in front of the stage. Its driver hands a copy of Burnout 3 to Roy Jones Jr. who holds it up and announces it as the winner. Alex Ward, the game’s director of design, comes onstage to accept the award with DJ Stryker, a Spike TV mainstay who also appeared in the game as himself. Alex Ward notes while accepting the award that “78 people made this game,” a number so specific that it genuinely endeared him to me. Short as it was, this moment felt like an actual acceptance speech as opposed to just a two-sentence quip, for once.

Funkmaster Flex then introduces his “new favorite actor,” Giovanni Ribisi, who was in Call of Duty (as in, the very first Call of Duty game ever, titled simply that, back in 2003). Ribisi immediately hands off to Sum41, performing “No Reason,” which apparently appeared in NFL Street 2 so that’s why they’re at the show. The 2004 Spike TV Video Game Awards is inspiring me to coin a music genre called “gamercore” that is made up of every musician who has appeared onstage at this event.

After a commercial break, Funkmaster Flex introduces Danny Masterson by saying, “While his castmates were off dating Lindsay Lohan and Demi Moore, he was playing video games.” This was, reportedly, not all that Masterson was doing during this time period.

Masterson appears to be chewing gum before introducing one of the Game of the Year nominees, which is Half-Life 2. Instead of being a trailer for the game, this spot includes interviews with various anonymous gamers (I assume, anyway, since none of them get chyrons). The first one says “I like Half-Life 2 because it’s a continuation of the original Half-Life.” It sure is, buddy. It sure is! Another guy tells us that it is “in fact mandatory to replay every level.” I mean, it’s not. But I get it.

Funkmaster Flex then reads one of the more horrifying jokes of the night off the teleprompter: “She’s the star of the upcoming movie Alone in the Dark, and I know every guy in here wants to be alone in the dark with her.” Yikes!

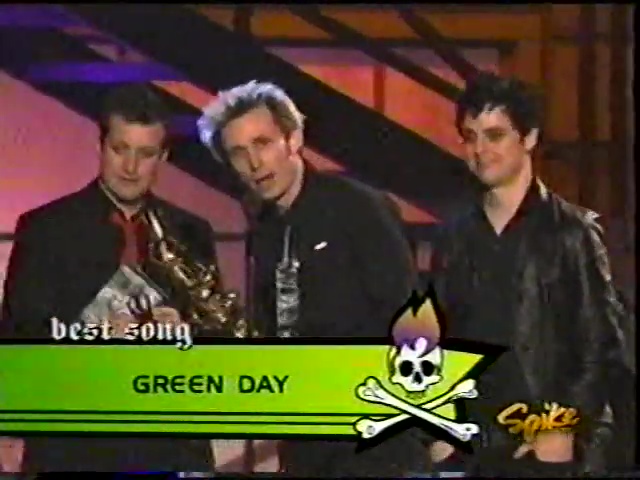

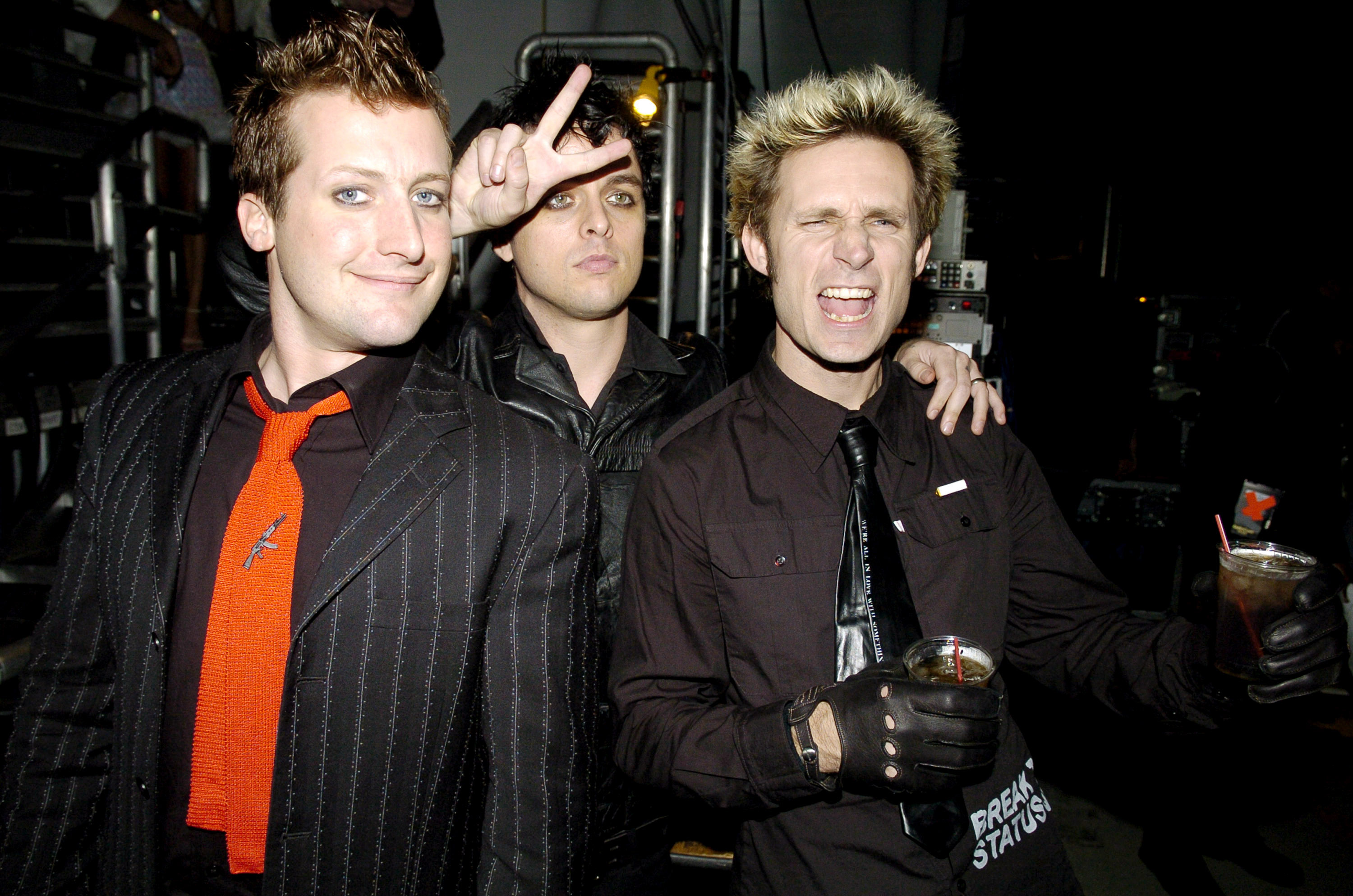

Anyway, it’s Tara Reid. We get a cutaway to a bunch of guys in the crowd full-on hooting and hollering at her. Reid introduces Best Song in a Video Game, which is actually a lineup of pop songs that were licensed for games as opposed to tracks that are original to the games in which they appear. The winner is “American Idiot” by Green Day, which appeared in Madden NFL 2005. A new classic gamercore track. The idea of a Green Day song in a Madden game winning an award for Best Song in a Video Game is making me feel disconnected from reality and the normal meanings of words.

Steve Schnur goes up to accept the award alongside part of Green Day; Schnur’s job is listed as “Executive in charge of music” at EA (this appears to still be his same job, 20 years on). Clips from Madden play in the background, because this is an award honoring a Madden game, technically. It’s hard to make out the bandmates in this low-res video, but I’m pretty sure that’s bassist Mike Dirnt who elects to talk into the mic, holding up his hand to show off what he calls “gamer gloves” (they appear to just be regular black leather driving gloves, not even fingerless ones or anything). He then holds up his Vector Monkey and says, “That is one funky monkey. Mmm.” Again, this is the standard length and tone of this event’s acceptance speeches.

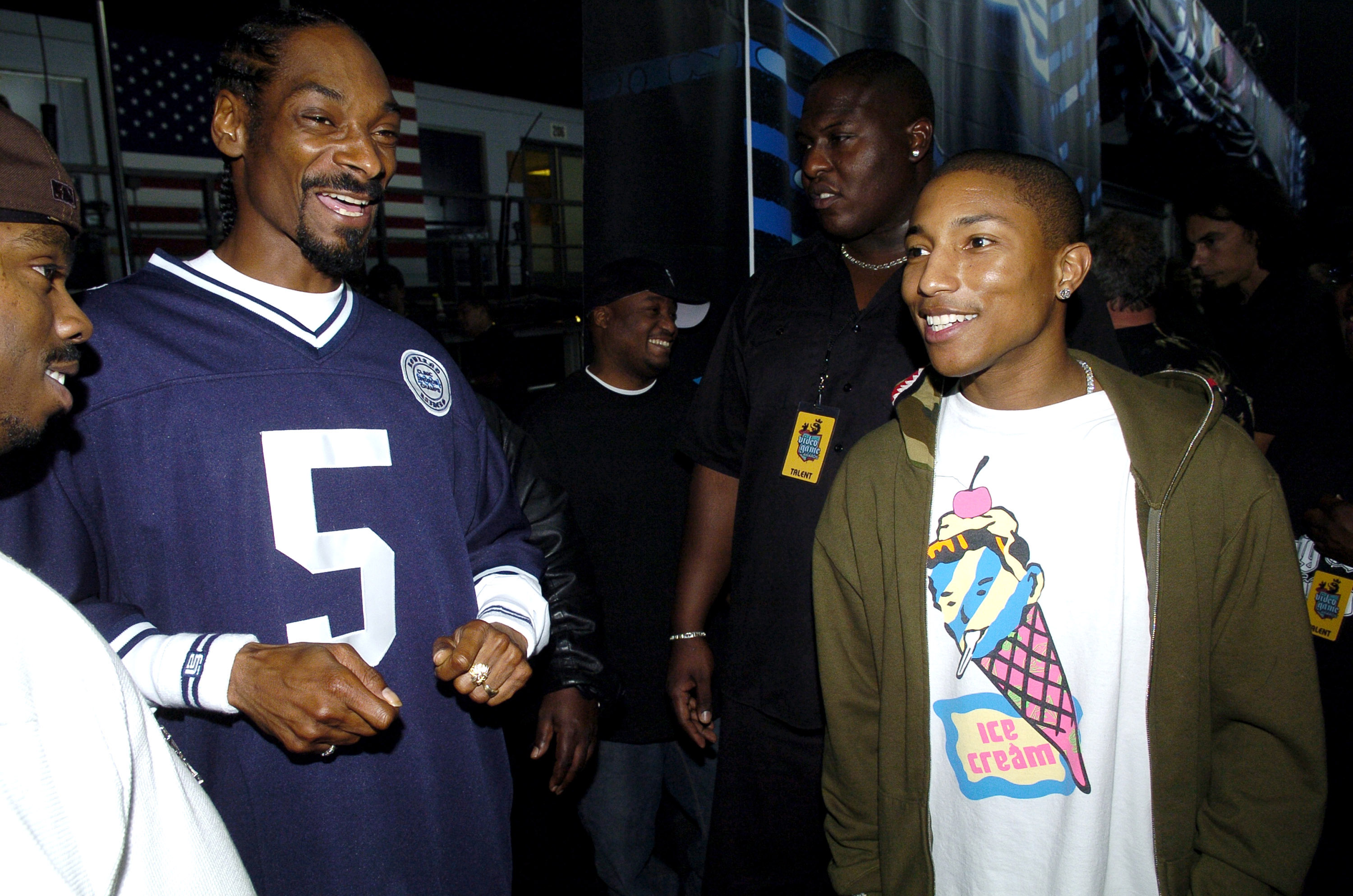

Now it’s time for Lil Jon and the East Side Boys. They’re not performing a song, though, they’re actually just introducing “the world premiere performance” of Snoop Dogg’s song “Let’s Get Blown.” Pharrell sings backups on this one so he’s here too. Snoop walks out and the crowd loses it. A couple of seconds pass. “Can we get the music?” Snoop asks. Nothing happens. “Well, can y’all play it? Come on,” he says. The musicians behind him finally start and it’s not entirely clear to me if that was an intentional delay or not.

What happens next is lost to time, but the YouTube rip picks back up with members of Papa Roach running through multiple awards at once, which is very modern-day Game Awards of them: We get Best Fighting Game, Best Action Game, Best Graphics, Best New Technology, Best Handheld, Best Mass Multiplayer Game, and Best Cyber Vixen of the Year (featuring a custom-made video clip of the winner, Rayne from BloodRayne 2, who thanks the voters).

I’m realizing I have barely any time left in the video that I’m watching. My personal grand finale before the YouTube video cuts out is JC Chasez, of NSYNC fame, who comes out to introduce a highlight reel for Game of the Year nominee Burnout 3: Takedown. (Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas takes home the big prize, but I was not treated to anyone at Rockstar accepting their Vector Monkey.)

The main thing that’s changed in 20 years is that flagrant, in-jokey misogyny isn’t a part of The Game Awards anymore, and I need everyone to understand how grateful I am for that cultural shift because… I’m about to admit that I do think something else was lost when The Spike TV Video Game Awards died and the modern TGAs rose up from the ashes.

The wooden but well-intentioned joke-telling on the part of slightly uncomfortable celebrities reminds me more of the Oscars than the current-day Game Awards do, at least from the vantage point of making up the pieces of a show that has decent pacing and a sense of humor about itself. In between lowering Victoria’s Secret angels onto the stage via wire and telling a downright disturbing joke about Tara Reid, this show also managed to get mics in front of more women than multiple iterations of the modern-day Game Awards. (I have no possible moral justification for the poor woman who read off a cheat code in her underwear, though.) It’s also undeniable that by featuring hip-hop and punk rock artists of the era, the show ended up with a far more diverse lineup of famous, entertaining guests. If the teleprompter jokes had been just a bit better written, I would have had to write an article about how this show was legitimately decent.

There is plenty of shit to laugh at here. Bleach-blond spiky hair, “gamer gloves,” Mountain Dew — these are the trappings of a bygone era. But I have to admit, this show was also just plain fun to watch. It absolutely helped that it wasn’t stacked to the gills with back-to-back advertising for upcoming games. Instead, it was a show that was designed to be an entertaining romp celebrating 2004 in gaming.

Now I’m sitting here thinking about how the best part of Half-Life 2 is the fact that it was a continuation of Half-Life. I can’t deny that.