There’s a new Dragon Age game out, and for fans who’ve been tapped into the series for 15 years, it’s an incredibly exciting time (especially since 10 of those years involved simply… waiting for this game). But 15 years and three games means a lot of lore for new fans, especially if you’re a new fan coming from last year’s sprawling choice-driven fantasy RPG.

If you’re a fan of Baldur’s Gate 3 who’s decided to take a chance on Dragon Age, jumping right into the lore can be a lot. It’s not totally inaccessible, but there are a lot of big reveals that will feel more impactful if you have some context about the world of Thedas and what the previous three games have built toward.

Dragon Age is defined by apocalypses

The history of Dragon Age’s setting is kind of like a rolling succession of apocalypses. For close to a millennium, Thedas (an internal BioWare abbreviation for “The Dragon Age Setting” that stuck) has been plagued by five Blights, in which monsters called Darkspawn erupt from underground, spreading a bloodborne disease (the Taint) that turns victims into more Darkspawn.

But even before the Blights, Thedas was rocked by upheavals — the rise and fall of the Tevinter Empire, which at one point had conquered nearly every country you’ll see on Dragon Age: The Veilguard’s world map, and the mysterious fall of the elven empire that preceded it. History, in Thedas, is very much written by survivors, victors, and other biased sources, and all this upheaval has meant that even scholars don’t know what really happened “back then.” The Dragon Age games themselves are often about revealing that what everyone thinks is true is at best a simplification and at worst an outright lie.

Dragon Age: The Veilguard’s setting in Northern Thedas is a great example of this: It’s a bunch of countries that the games have never actually let us visit before, and that have until now largely been defined by outsiders. In previous Dragon Age games, Tevinter is known as the last remnant of the conquering empire whose yoke was thrown off centuries ago, a place where mages sacrifice slaves to fuel decadent blood magic (think late Rome, or Byzantium). Rivain is known as a nation of piracy and witch-like seers (and sort of the Spanish Caribbean in the age of sail?), Antiva as a mercantile nation ruled by a cabal of unstoppable assassins (fantasy medieval Italy, but with Spanish accents for some reason), and Nevarra as a creepy place where they let spirits inhabit the bodies of their dead loved ones in massive tombs (instead of cremating them, like basically everyone else in Thedas does).

But if you know anything about Dragon Age, you know that what we “know” about these places is, again, at best a simplification and at worst an outright lie. If you’re a new fan, Dragon Age: The Veilguard will give you everything you need to know about them, and it’ll be the old fans who’ll have to update their assumptions.

What is the Blight?

…Basically zombie infestations. Except in this case, the zombies are called Darkspawn and they’re more akin to the “infection” zombie trope versus the “resurrected undead” one. The Darkspawn are always around, usually lurking underground. But a Blight kicks off when they corrupt a powerful sleeping dragon (one of a pantheon of “the Old Gods” once worshipped in Tevinter), which ends up rising as an Archdemon and leading a horde. Usually, it turns everything dark and gray and dead. The only way to stop the Blight is to slay the Archdemon that’s leading it, and the only way to slay that Archdemon is to have a Grey Warden sacrifice their life to do it.

The Grey Wardens are a mysterious order dedicated to eradicating Darkspawn. Their joining ritual gives them a minor version of the Taint that allows them to sense Darkspawn and fight them. The first game’s protagonist was a Grey Warden who fought off the Blight in Ferelden (fantasy England), so that faction has been a huge part of the lore from the very beginning.

One of the series’ biggest mysteries is how the Blight came to be. Most humans who follow the in-universe fantasy Catholicism attribute it to divine punishment from the Maker (God), after a group of human mages from Tevinter got too cocky and marched upon the Golden City (heaven). But there have been hints in past games that this widely believed explanation is not the true story, especially considering how comparatively recently humans have been around Thedas.

What are gods in Dragon Age?

If you’re used to Baldur’s Gate 3, in which characters can talk with gods, kill gods, and even become gods, you’ll want to adjust your expectations for Dragon Age. Andrastianism, the largest human religion in Thedas, worships a single god, the Maker, who does not speak to his subjects, and the games have never explicitly weighed in on whether he even exists.

Maker-worship began centuries ago when his prophet, Andraste, rallied the armies of Southern Thedas to rise up and overthrow the Tevinter empire. And though her forces did succeed in liberating the nations that eventually became Ferelden and Orlais (fantasy England and fantasy France), she was betrayed, captured, and burned at the stake in the capital of Tevinter.

Andrastianism (often simply called “the Chantry”) has huge Catholic Church vibes — but if Joan of Arc was Jesus, and if one of those anti-popes had actually succeeded in causing a full schism. The Cult of Andraste eventually grew into the dominant organized human religion in Thedas, administered through churches called “Chantries” and led by a pope-like figure called the Divine. Then the Chantry split into two based on a disagreement about the role of magic. The Southern Chantry adopted the idea that mages were dangerous and should be controlled by the church, while Tevinter’s Chantry broke away and appointed its own Imperial Divine (known as “the Black Divine” in the South, which we mention only because it’s metal as fuck), adopting the idea that the Maker wanted his people to use magic to its fullest extent, actually.

Both Chantries teach that for the crime of killing his prophet, the Maker turned away from his people until such a time that the words of Andrastianism’s holy text, the Chant, were sung in all corners of the world. But the scattered elves of Thedas, who are treated as second-class citizens in many places, especially in the South, have an even more distant relationship with their gods. For centuries, elven legend held that the trickster god Fen’Harel, the Dread Wolf, trapped the elven pantheon in their realm in the heavens, cutting the elven people off from the protection of their gods and leading to the fall of a golden elven civilization.

But as recently as the final DLC of Dragon Age: Inquisition, the heroes of that game discovered that the elven gods were never gods at all: They were just really powerful mages who had enslaved their own people. One of that game’s companion characters, Solas, turned out to secretly be Fen’Harel, recently woken from a thousand years of slumber, an ancient rebel who had sealed those elven mages away by creating a barrier between the material world and the Fade.

But for as much as Dragon Age games show the flaws of organized religion — particularly the bias in how institutions like the Chantry massage history to their own advantage — it is also a franchise full of characters who have deep and individual relationships with faith.

OK, so how do mages work?

Unlike in D&D lore, where magic can come from a wide variety of places, the magic in the Dragon Age world comes from one specific place: the Fade, a metaphysical realm separated from the world by a barrier known as the Veil. Humans, elves, and Qunari enter the Fade in their dreams; dwarves, however, are cut off from it and cannot dream (Why? Nobody knows).

The Fade is a reflection of the actual world, populated by spirits, beings of pure magic who often embody a character trait like Compassion, Faith, or Justice. There are also spirits who embody negative traits, like Despair, Vengeance, or Spite, usually because they’ve been corrupted in some way — or because the limited human viewpoint sees them as vices. Many people refer to these ones as demons, but the more we’ve learned about how spirits work, the blurrier the line between sprites and demons gets. Regardless, they’re all fueled by the presence of the human emotions they embody, which means demons tend to be aggressive and often appear when things already kinda suck.

Anyway, some humans, elves, and Qunari are born with a connection to the Fade, which allows them to manipulate it in the form of magic. This also leaves them more vulnerable to possession by harmful spirits, which is the source of the South’s fear of mages. Magic can be used to manipulate elements, converse with spirits, heal wounds, and shape-shift, among other things.

There’s also a special, magic, glowing blue mineral called lyrium, which strengthens a mage’s connection to the Fade. Only dwarves can mine raw lyrium without side effects, because they’re cut off from the Fade. Previous games also introduced the concept of red lyrium, which is lyrium corrupted by the Blight that drives people to madness. It’s bad! TL;DR: glowing blue rock = powerful, revered, good; glowing red rock = powerful, destructive, BAD BAD BAD.

In the previous three games all set in Southern Thedas, being a mage was a big no-no, because the Chantry had a doctrine that “magic must not rule over man,” which everyone interpreted to mean “magic is evil.” But it’s been over 10 years since the Mage Rebellion fixed that to some degree, and the regions you visit in The Veilguard have historically been pretty chill with most mages, so all you really need to know is that there’s some passing mentions to how barbarically the South treats their mages.

Blood magic is generally seen as a bad thing, though the games’ definition of exactly what blood magic is has varied. A lot of the Death Caller abilities in The Veilguard are actually pretty similar to what previous games called blood magic. (And this can probably be attributed to how the different regions view magic). For the purposes of this game — and Tevinter specifically — blood magic involves using the blood of others to augment magical powers, oftentimes utilizing it to control others’ minds and summon demons. Blood magic is unique in that it actually doesn’t require tapping into the Fade, and in fact, it makes entering the Fade harder.

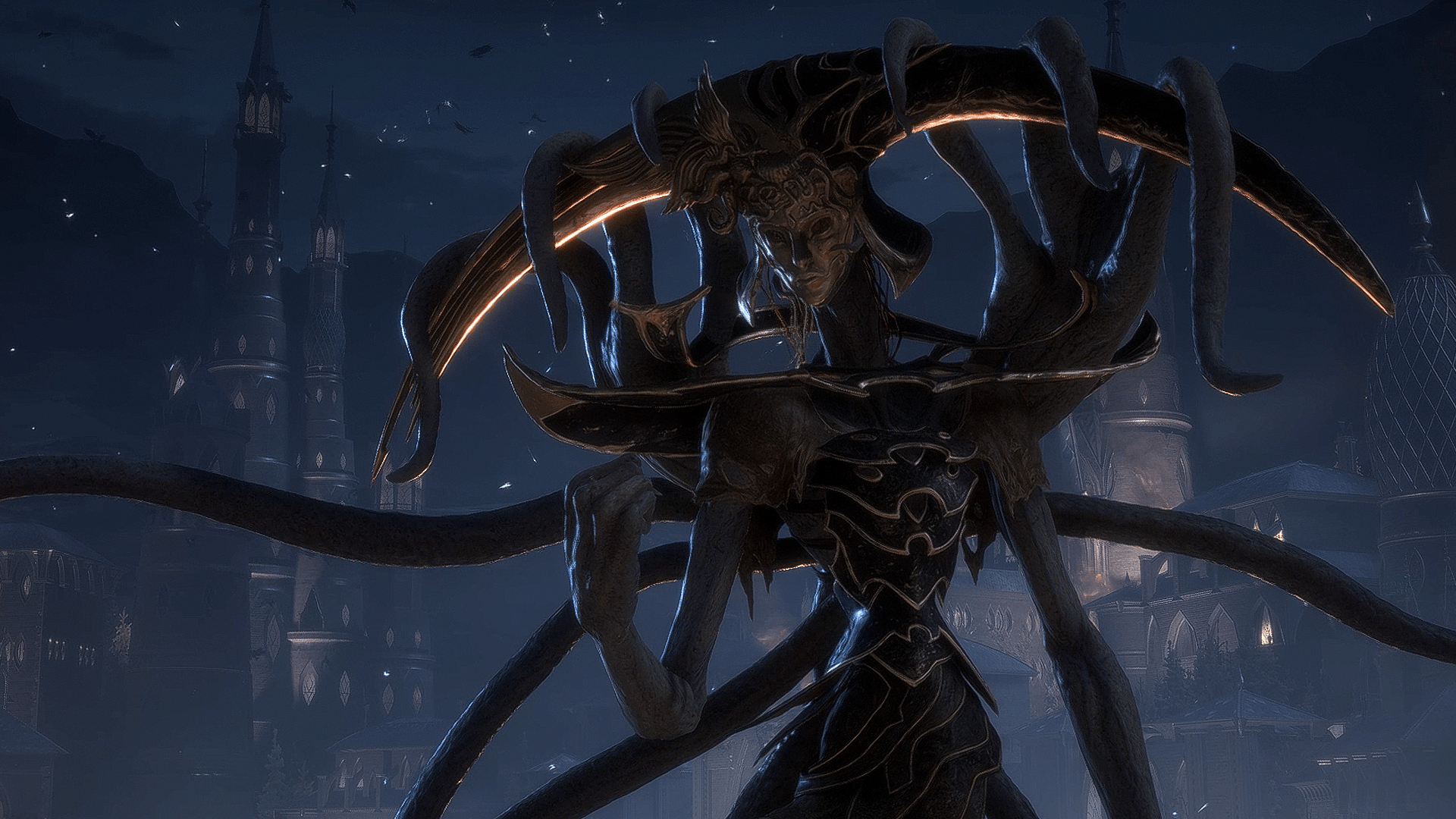

Who is this Solas guy and what does he want with the Fade?

Your player character initially knows that Solas is actually Fen’Harel, the elven god of lies, who is out to destroy the world by getting rid of the Veil that separates the Fade from the real world.

That’s the quick and dirty version.

The longer one is that in the previous game, Solas was introduced as Just Some Mage who decided to come and help the Inquisitor (the player character) out of the goodness of his heart. He spends the entire game with the Inquisitor, sharing stories of his explorations of the Fade in his dreams and his knowledge of magic. The Inquisitor could forge a friendship with him, or find him annoying, or — if they were a female elf — start a romance.

But Solas mysteriously vanishes after the events of the main game, and in the epilogue DLC, he reveals that he was the power behind Inquisition’s biggest bad guy. When he woke up from his thousands of years of slumber, he was devastated to find that his actions cut the world off from magic — and deprived the elven people of their culture and heritage. His first attempt at fixing the world involved a massive explosion that ripped a tear in the Veil, and also unintentionally gave the Inquisitor (who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time) the Anchor, a mysterious glowing green mark that could seal the rifts in the Veil. This time, Solas wants to get it right, even if that means destroying the known world in the process. And in the case of a romanced Inquisitor, even if it means losing her.

The default setup in The Veilguard is an elven Inquisitor who romanced Solas and wants to save him from himself — which isn’t so much BioWare declaring canon as it is setting up the juiciest storyline for people who didn’t play the previous game. But if you want to mess with the defaults, you can create a new Inquisitor who didn’t romance Solas at all, or who wants to stop him instead of save him (or any other combination). Regardless of who they romanced, the final big choice the Inquisitor makes in Inquisition’s DLC Trespasser is whether or not to save or stop Solas. Oh, also, he cuts off the Inquisitor’s hand, since the Anchor is slowly killing them.

Who is Varric?

Varric Tethras is a fan-favorite Dragon Age companion who is now on his third game running as a major character. He started out as a full companion character in Dragon Age 2, a game where it’s easy to piss off your companions so much that they leave or outright stand against you. But Varric was designed to be your biggest supporter, no matter what — he was the game’s narrator, and so he had to be there for the whole story.

That early role as your best bud endeared the deadpan dwarf with a heart of gold to many players. He returned as a companion character in Dragon Age: Inquisition, where he had a caring but more standoffish relationship with the Inquisitor. His side hustle as Thedas’ most popular author has had him publishing tell-all books about the heroes of Dragon Age 2 and Inquisition, so he’s intimately familiar with the wildest events in Thedas’ recent history. It was his brother’s risky underground expedition that first discovered red lyrium, one of his friends started the Mage Rebellion, and he adventured alongside Solas with the Inquisition, helping discover the truth about the elven gods.

And now here he is, 20 years older than when we first saw him, gray-haired, with new facial scars, still adventuring on (presumably?) the behalf of the Inquisition, and seemingly really invested in talking Solas down from his whole destroy-the-world plan. To give you a bigger peek behind the fandom curtain: A lot of us are really worried that his narrative role in Veilguard is to make us very sad, in one way or another. Knock on wood he makes it out OK, but with BioWare, you never know.

Veilguard won’t give you the same freedom as Baldur’s Gate 3 — but that’s the point

Computer RPGs can never be as flexible as a tabletop role-playing game, and different franchises work around this problem in different ways. Baldur’s Gate 3 made its mark with a frankly unbelievable level of choice complexity. Historically, Dragon Age has taken a different tack.

Lacking the technological, financial, or human resources necessary to make a game that complex, Dragon Age games are often very directly about characters whose choices are constrained. That franchise theme that the real history was usually more complex than the story told about it? Dragon Age 2 applied that idea directly to its main character, Hawke, with a framing device in which Varric was being interrogated about the book he wrote about Hawke’s life, on the suspicion that it was all too coincidental for so many bad things to have happened to one person without it being a plan all along.

In Dragon Age: Inquisition, the Inquisitor is swept up in a narrative — that they’ve been touched by the Maker — regardless of how they personally feel about it. All they know is that if they don’t pick up the power of that story and use it for good, the world will end.

Dragon Age is, in many ways, the “doomed by the narrative” CRPG franchise. The choices that tend to be reflected most in future games are the impact your character has on their companions, not the world, as if to say: Individuals can’t actually change the world on their own; what matters is who you love and how you do it.

“Yeah, that still kind of sucks, though,” you might say. “It’s more fun when a player can make choices that really matter.” But look at it another way: Given the sheer number of divergent endings to Baldur’s Gate 3, it would be prohibitively difficult to make a direct sequel to it. But Dragon Age fans have been able to return to Thedas, and get an update on at least some of their old buddies (or in the case of characters like Varric, adventure alongside them again), for three sequels and counting.

There’s nothing inherently bad with Dragon Age offering less choice than Baldur’s Gate 3 — you just get different results for it. Give Dragon Age: The Veilguard a shot, and you just might find yourself hooked.